“Each night, every night someone dies. Sometimes one, three, five, ten, twelve… the most I think in one night was 24.”

“Each night, every night someone dies. Sometimes one, three, five, ten, twelve…the most I think in one night was 24.”

– Raffy Lerma –

While the international community has condemned the extrajudicial killings of suspected drug users in the Philippines, Filipinos have largely resisted this condemnation. Traditional media sources have contributed immensely to the creation and legitimization of a toxic narrative that posits killing as the only option in this so-called war on drugs. This vicious war has resulted in vigilante killings, secret jails, and immense fear. A group of photographers, writers, and filmmakers have been working to counter this narrative by documenting the violence and the impact of the killings on local communities. Their goal is to open the eyes of Filipinos who would rather ignore or do not believe what is happening every night on their streets.

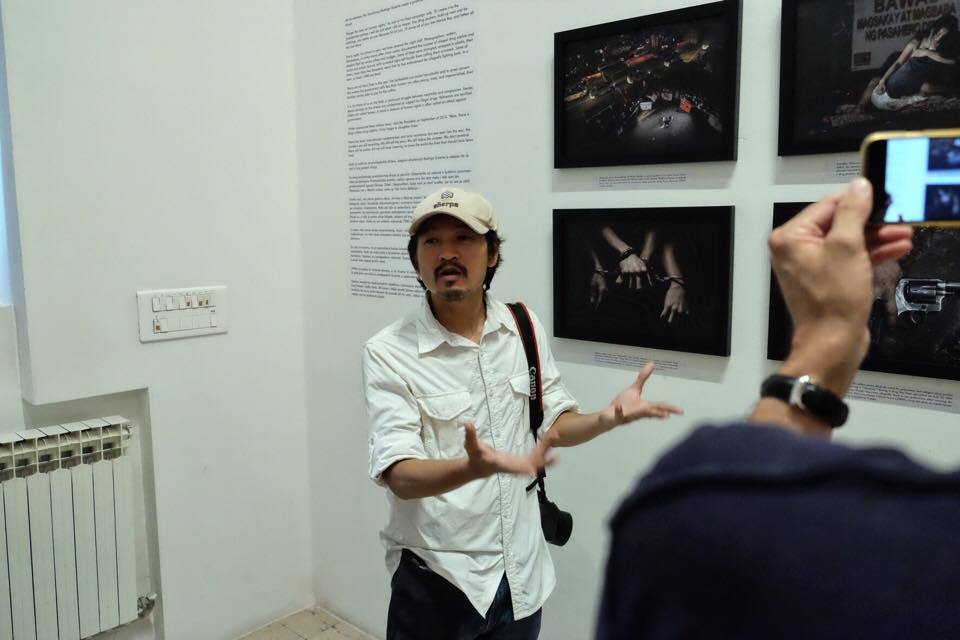

‘Philippines War on Drugs: The Nightshift’ is a photography and video exhibition that displays the extreme violence caused by the government’s war on drugs. The exhibition features work from twelve nightshift regulars: Ezra Acayan, Alyx Arumpac, Dante Diosina, Kimberly Dela Cruz, Vincent Go, Eloisa Lopez, Carlo Gabuco, Brother Jun Santiago, Basilio Sepe, Jes Aznar, Raffy Lerma, Jay Ganzon, and Linus Escandor. On 30 June 2017, one year to the day since President Rodrigo Duterte took office, the exhibition was opened at the 2017 WARM Festival by photographers Raffy Lerma, Eloisa Lopez, and Ezra Acayan.

Drug-Free By Any Means Necessary

The war on drugs began a little over a year ago with the election of President Rodrigo Duterte. Duterte had a larger-than-life persona as a strongman before his rise to the presidency. He was nicknamed “The Punisher” and “Duterte Harry,” both references to violent vigilante killers. He earned these monikers through his association with alleged death squads during his time as mayor of Davao. This narrative of Duterte as vigilante hero has been furthered by claims that crime rates have dropped drastically in Davao. Stories of Davao being rated as one of the safest cities in the world circulated throughout the Philippines. However, this ranking was achieved through a public opinion poll with no statistical data behind it. Philippine National Police statistics for 2010-2015 reveal Davao had the highest murder rate and second highest rape rate in the country.

Throughout his presidential campaign, Duterte utilized his Punisher persona to convince Filipinos he could clean up the entire country, just like he cleaned up Davao. He promised to cleanse the country of drug addicts and drug dealers through any means necessary. This included vowing to issue shoot-to-kill orders to police and to provide bounties for the bodies of addicts. He also encouraged regular Filipinos to do their part in ridding the country of criminals: “If you know any of addicts, go ahead and kill them yourself as getting their parents to do it would be too painful.” The killings started before his inauguration and, in his one year as president, Duterte has waged a bloody all-out war on drugs resulting in at least 7,000 deaths. Human Rights Watch reported the police are responsible for at least 3,116 of those deaths.

The Nightshift

Traditional media was hesitant to report on the deaths occurring each night. Local photojournalists have taken it upon themselves to document and report what is happening on the ground in this war on drugs. Each night, they document the bodies of suspected drug users and dealers that are spread across Manila. Some are shot, others strangled, and some have their wrists bound. Many are left with cardboard signs identifying them as criminals and warning others to avoid their fate. They move from crime scene to crime scene, racing to arrive before the police cordon off the area and forensics removes the body. The majority of the victims are young males from poverty stricken communities. Those working the nightshift face a constant battle between objectivity and compassion. Reports of the bloodshed occurring each night are met with condemnation. They are perceived as support for the drug trade and an attack on the government.

The nightshift differs greatly from the daily grind of traditional journalism. It is not ruled by competition or a need to one up your fellow journalists. It is a collective of photographers, filmmakers, and writers working towards the common goal of documenting and reporting the drug killings. They help each other by sharing sources and giving tips on the latest crime scene, “In the nightshift, I really feel everyone has each other’s backs,” (Eloisa Lopez, photojournalist). In the nightshift, it does not matter which news organization you work for as long as you are working towards greater public awareness of the drug killings.

Shifting Narratives

In March 2017, an inquiry into the allegations of Duterte’s use of death squads in Davao was dismissed due to lack of evidence. The photographers, writers, and filmmakers working the nightshift are determined to prevent this from happening again by documenting this nightly war.

Raffy Lerma

Raffy Lerma is a veteran photojournalist based in Manila, Philippines. He currently works as a staff news photographer for Philippine Daily Inquirer and has been documenting the violence since Duterte took office. Lerma has taken a clear stand against the killings, “I am for the drug war, but not the killings.” Lerma’s work served as a turning point in traditional media’s hesitation to report on the violence. His most iconic photo of the war on drugs was posted on the front page of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, along with an article questioning the morality of the violence. This piece opened up the public dialogue on the events unfolding.

It was the third killing of the night. As a standard procedure, a police cordon blocked journalists and bystanders. The scene, however, was not standard. Jennelyn Olaires was inside the cordon cradling her husband’s lifeless body. Michael Siaron, a pedicab driver, was accused of being a drug pusher. He was shot and killed by masked men on motorcycles. Family members are normally not allowed inside the scene, a forensics protocol to preserve the integrity of evidence. Forensics arrived late to this location, however, after processing earlier crime scenes. Lerma described, “feeling like a vulture” covering the scene, “I remember her saying ‘stop taking pictures already, please help.’ I asked the police ‘what are you doing?’ The police said ‘he is already dead nothing can be done.’” Lerma could tell this was going be a strong photo but did not know if it would be published. The photo was published in the Sunday edition of the Philippine Daily Inquirer with the title ‘Thou Shall Not Kill’.

The story elicited a strong reaction, one that had not previously been inspired. The photo took on a life of its own as people compared it to Michelangelo’s sculpture ‘Pietà.’ Even the president reacted to the story. During his first State of the Nation Address, Duterte called the photo overly dramatic and claimed it was not real. His supporters alleged the media took the photo in a studio with the use of actors. This was the first instance of major public opposition to the war on drugs.

Eloisa Lopez

Eloisa Lopez is an independent photographer and writer based out of Manila, Philippines. Her work has been featured in The New York Review of Books, TIME (online), Der Spiegel, and Philippine Daily Inquirer. Her work focuses on human rights, women, children, and religion.

On her first nightshift, Lopez went to Tugatog Public Cemetery in Malabon. She was expecting a bloody scene, guns, and several packs of meth – she was expecting the typical scene reported by the media. Instead, Lopez was met with the body of a 7-year-old girl who had been raped, murdered, and left naked in the cemetery. Next to the body was the girl’s grieving family. Police reported the assailant was the father’s friend, an alleged drug addict and alcoholic. Lopez followed the suspect to the police station. In that moment she understood why people supported the drug war killings, “I was already feeling like this drug suspect needs to die now.” On further reflection, Lopez realized this horrible crime did not justify the killing of all drug addicts. To have no due process, to have no human rights would make her like just like the suspect she hated.

Ezra Acayan

Ezra Acayan is an independent photojournalist who has previously worked for Reuters. Acayan has been covering the most recent killings. He has challenged normative perceptions of the killings by posting photos and stories of those who have been killed on social media.

Trolleys are a staple of Filipino society. The trolley system was started by impoverished people as a way to make money. They are an inexpensive alternative to taking a bus or a train. Two bodies were left near trolleys Acayan regularly rode. He was called to the crime scene and had to take a trolley to reach it. The ambulance that arrived to take away the bodies could not reach their location; they were forced to put the bodies on a trolley to bring them up. Acayan then rode in a trolley traveling directly next to the bodies. He described the night as surreal. This was a community he knew, a trolley he rode. What was normally used to transport commuters and brought livelihood to the neighborhood was now carrying corpses. Acayan used to have happy memories of Manila, now he sees the bodies he photographed everywhere he goes.

Government Response

The government has pushed back against the stories of carnage and despair. In addition to creating an illusion of widespread support, Duterte has put together an ‘army of trolls’ to discredit and harass dissenters online. Acayan has been a large target for online harassment. His posts are met with messages calling him a liar or a supporter of the drug war. He also receives hate messages wishing for his death or for the rape and murder of his female relatives by drug addicts. Online trolls also post propaganda messages supporting Duterte’s authoritarian rhetoric. Acayan and his colleagues view these attacks as a sign of their effectiveness; the more attacks you receive, the more effective you are.

Duterte recently held a press conference reiterating the need to reduce the drug trade. He assured citizens the volume of drugs would be at its lowest by the end of his term in 2022. Duterte also reminded police to kill only those suspects who resist and fight back. He joked, “If the suspect refuses to fight, make him fight you anyway.”

—

The Balkan debut of “Philippines War on Drugs: The Nightshift” took place during the 4th annual WARM Festival in Sarajevo from 28 June to 2 July 2017. Organized by the WARM Foundation in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), the WARM Festival brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.