The Arab Spring in Syria resulted in the influx of over 5 million refugees into Europe, tens of thousands of whose bones were swallowed by the Mediterranean Sea. While Syria burned and refugees ran in the pursuit of a safer life, Kostas Pinteris from the island of Lesbos offered them a helping hand.

The Arab Spring in Syria resulted in the influx of over 5 million refugees into Europe, tens of thousands of whose bones were swallowed by the Mediterranean Sea. While Syria burned and refugees ran in the pursuit of a safer life, Kostas Pinteris from the island of Lesbos offered them a helping hand.

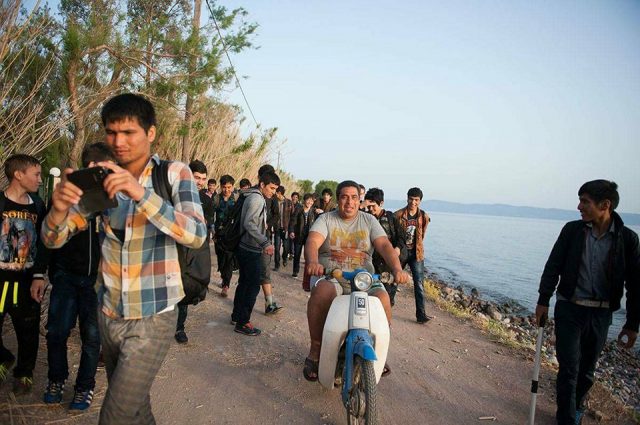

The island of Lesbos, a popular tourist destination that has left people breathless for decades, is now a safe haven for countless Syrian refugees who are running scared from the whirlwind of war that continues to unfold in their homeland. The war in Syria has caused a large migration of people into Europe, has shown Turkey’s humanity, has split the European Union, and, it is safe to say, was one of the triggers of Brexit.

Amidst all this, in Skala Sikiminia, lived Kostas Pinteris, a humble Greek fisherman who made his living on the sea. He spent his days on his boat, from which he threw his net and reeled in his fishing pole lines. At night, he slept in his family home where he lives with his parents. His quiet fisherman’s life was soon disturbed by what was happening in the world. His phone would ring non-stop, often in the middle of the night, and his family home became a volunteer center. His fishing boat became a refuge for those drowning in the sea, and his Nobel Prize nomination served as a slap in the face to all the “Europeans” who refused to help the refugees.

When Kostas appeared among us, we didn’t even know who he was. We saw a large, yet calm and steady man. In his eyes, there was a quiet liveliness, but also confusion at the sight of all of us who came to Turkey from different parts of Europe to participate in an event organized around the topic of multiculturalism. His arms were strong and his palms scuffed and rough from the rope of his anchor. He sat close to me and calmly watched as the group complained because dinner was late.

To break the silence, I asked him where he was from and what he did for a living. He briefly replied that he was a fisherman from Sikimini, a small village in the north of Lesbos, 10 kilometers away from Turkey by sea.

“When I was a child, I did agricultural work. We’d spend days in the olive plantations with our parents. I’d spend my free days with my grandparents. They’re the biggest reason for my passion for ocean waves and fishing nets. That’s when I fell in love with boats and wished to own one when I grew up,” said Kostas. Then, with pride in his voice, he continued, “I’ve had my own boat for several years already and I used to make a decent living from it.”

Luckily for me, the Turkish restaurant service was particularly slow and Kostas was generous and willing to indulge my curiosity. As I sat there surprised to hear him speaking in the past tense, he discreetly began to tell his heroic story.

“It all began as a result of the wars happening in the world, at a time when many wished to reach European soil because they believed it was their ticket to salvation. They came in small boats in ever-increasing numbers. I must admit that I was initially very skeptical. Then more started to arrive in ever smaller rafts and boats.”

With a sigh, he momentarily paused before continuing on with his story. “I stopped fishing and my life was turned upside down! I now fished people. Sometimes, I even dragged dead bodies out of the sea.”

With my look of apprehension, the real-life superhero proceeded: “Yes. That is my life! I’ve saved thousands of misfortunate migrants. Unfortunately, it was too late for some of them, but I did my best. During such periods, I wouldn’t have time to earn a living for myself for days and my life just revolved around helping those less fortunate. I lived exclusively off of my parents.” As he spoke this last sentence, he smiled briefly as if he were apprehensive of judgment on my part.

He looked upon my silent stare and the selfishness that it must have reflected as I contemplated how he wasn’t afraid for himself.

As if he had read my thoughts, a turbulent and emotional reaction followed, like that when you want to defend yourself: “Afraid? Of course I was afraid! Calls were coming in the middle of the night, often when the sea was rough with raging winds. The Coast Guard was not allowed to react and the colleagues who usually went ‘fishing people’ with me would have been silent, which I understood considering they had families of their own. So, what are you supposed to do? You know you can help a mother, a child, or an old man, and you just turn over and continue to sleep? I could never live with such knowledge. Sometimes, there were so many people on my boat that I even became doubtful of its durability.”

There were many days and nights that Kostas left his family home to help people. And this was without ever receiving anything in return. However, as humble as the first moment I met him, he added: “When I would return home exhausted, it was always enough for me to know that I had saved lives that day or night.”

Then, with a dose of pride and an innocent, childlike smile, he recalled a night when he had saved a great number of people:

“When we reached land, the rescued stood in line to wait for me. Someone called out to me, and then, one by one, they came up to me to hug and kiss me, saying thank you! It was incredible. The elderly wanted to kiss my feet as a way to show their gratitude. I will never forget that moment, that night, and that feeling.”

Although dinner had been served a long time ago, I didn’t pay much attention to it. There was no helping my curiosity and my desire to hear more from this hero. Deep inside, I knew that it would be appropriate to wait for dinner to end and restrain my curiosity, but I was troubled by the thought of the injustice that a man who saves and has saved others is left to his own devices, without any help from the authorities.

Kostas put his cutlery down for a moment and said: “The European Union has never helped me or my village with a single cent during this crisis. I must admit, however, that after my boat broke down in February this year, the Greek government bought me some mechanical parts I needed, after which I fixed the boat myself.”

After a few moments of silence, during which he seemed to be thinking, he added: “Well, yes, that would be it. I’ve never gotten any other help.”

Mr. Gurkan, the organizer of the event in Turkey and the one who talked Kostas into coming, wasn’t sitting too far away from us. He spent the whole night trying to calm the participants regarding the late dinner and it didn’t seem to be following our conversation. Then, in one moment, just when our hero was about to pick his cutlery up again, he said:

“Kostas, why haven’t you told him about your nomination?”

I sat quietly looking at Kostas and waiting for the answer. In slight protest, more so because he even had to mention it rather than because we had interrupted his dinner once again, he said:

“Although this is not something particularly important to me, someone came up with the idea to nominate me for a Nobel Prize. At that moment, I was much more happy that the world was talking about my village and about Skala Sikiminia as a place with good people. I truly didn’t pay much attention to the nomination. I’ve helped, and will continue to help because I’m human and I believe that all humans have a right to life!”

Shortly thereafter, the sluggish Turkish waiters began collecting the plates that the excited mob cleared in a flash, and, although it was customary for participants to have a social gathering after dinner, I did not join them. I instead went to my room and thought about the man who helps yet asks for nothing in return, the man who is willing to risk his life and his greatest love—his boat, to help strangers who are negatively represented in the European media.

I thought about the man who, with his goodness, asked me whether I am selfish, and who, with his calmness, reminded me of all the moments I did not help. The man who inspired me to write about him with the knowledge that not even a thousand pages would be enough to illustrate his greatness!

The author would like to express a special thank you to the following individuals for providing their help in the writing of this article: Athanasioss Dimo for the selfless help he offered in the making of the text and Mr. Gurkan Akcaer, the organizer of the event in Turkey.

This publication has been selected as part of the Srđan Aleksić Youth Competition, a regional storytelling competition that challenges youth to actively engage with their own communities to discover, document, and share stories of moral courage, interethnic cooperation, and positive social change. The competition is a primary component of the Post-Conflict Research Center’s award-winning Ordinary Heroes Peacebuilding Program, which utilizes international stories of rescuer behavior and moral courage to promote interethnic understanding and peace among the citizens of the Western Balkans.

The Balkan Diskurs Youth Correspondent Program is made possible by funding from the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).