Visoko was once the cradle of Bosnia, a royal town where the coronations of Bosnian rulers occurred. Today, it is a municipality in which culture and anything culture related has died. Lejla Bečar explores the decline of her hometown.

According to the 1988 Archaeological Lexicon of Bosnia-Herzegovina, region 14 has 252 registered locations, 50 of which are in the Visoko area. Out of those, six have so far been declared national monuments of Bosnia, and three are on the temporary list of the Commission to Preserve National Monuments. Visoko is a town that was always proud of its rich history; Visoko is a cradle of Bosnia and the home of the Charter of Kulin Ban, a document that is considered a birth certificate of middle ages Bosnia. Visoko is a royal town where the coronations of Bosnian rulers occurred.

A time long gone.

Visoko today is a municipality in which culture and anything culture related has died. It died such a long time ago that most young people today do not even remember better times. I asked 12 friends – students – if they knew how many national monuments we have, and only one person, a student of archaeology, knew the correct answer. But are young people at fault for their ignorance and indifference, or should we blame someone else? I started the tour of national monuments with the one that was most important to me personally.

Not to me as an archaeologist, but to me as a young person from Visoko, a place I visited numerous times with my friends, and alone, spending beautiful days in the nature of the hills surrounding my town. The old town of Visoki.

It was declared a national monument in 2004. Archaeological research was conducted during 2007 and 2008. Afterwards, the restoration and conservation of dug-out walls was undertaken, which can be seen in the photographs. And this is what is present the old town of Visoki today. The photograph shows everything to be seen after one climbs the goat trails that are not adequate for anyone but extreme sports aficionados, not to mention people with disabilities, whose access would be illusory.

A table with basic information, the kind that usually stands next to national monuments, is lacking here. The only signs of literacy are the engraved names of people who thought their visit to the 700-year-old middle-age town of Visoki was so important that it should be immortalized in stone.

But when a royal town looks like this, when access is a challenge to anyone coming to visit, names in stone are the least of the problems; there are also piles of trash around and many remains of bonfires, but not middle-age ones – modern ones. Only in Visoko can you light a fire in a national monument and enjoy the view with some beer and barbecue.

The next location is right under Visočica Hill. The national monument is the Church of St. Procopius (shown above). It is located on the exit from the town, on the road to Kiseljak, and it is known among the youth as a good place to drink at night, write offensive graffiti or smash windows. The Church of St. Procopius was declared a national monument in 2004, and since then it has been decaying due to lack of care from those entrusted to take care of the cultural and historical heritage of Visoko.

Today the church keeps one of the largest collections of icons in Bosnia. They are being kept in an unimaginably inadequate conditions – lying on the floor of the church gallery and on the floor in the room above the Proskomide. The only thing keeping it from vandal attacks, something this building has been experiencing for years, is the layer of dust that covers them. The latest attack on the church occurred in mid-January of this year.

The center of Visoko is where the Tabačka Mosque, which was declared a national monument in 2003, is located. It is estimated that it was built sometime in the seventeenth century by tanners. The original mosque was damaged many times throughout history, mostly by fires and floods. After it was declared a national monument, the Project of Reconstruction, Restoration and Conservation 2005–2008 of the mosque was implemented.

Beside the mosque, a small harem was also declared a national monument, and it contains gravestones of agas, ulemmas and dervishes. These gravestones from early nineteenth century have acquired a new purpose in twenty-first century: people lean on them during the traditional days of trade in Visoko – the event is colloquially known as Vašer. If the visitors are not interested in relaxing in the outdoor cafes, they relax in the shade, leaning on the tombstones in one of the national monuments in Visoko. Of course, any symbols showing that this facility is important not only for the history of Visoko, but also the state of Bosnia, are lacking.

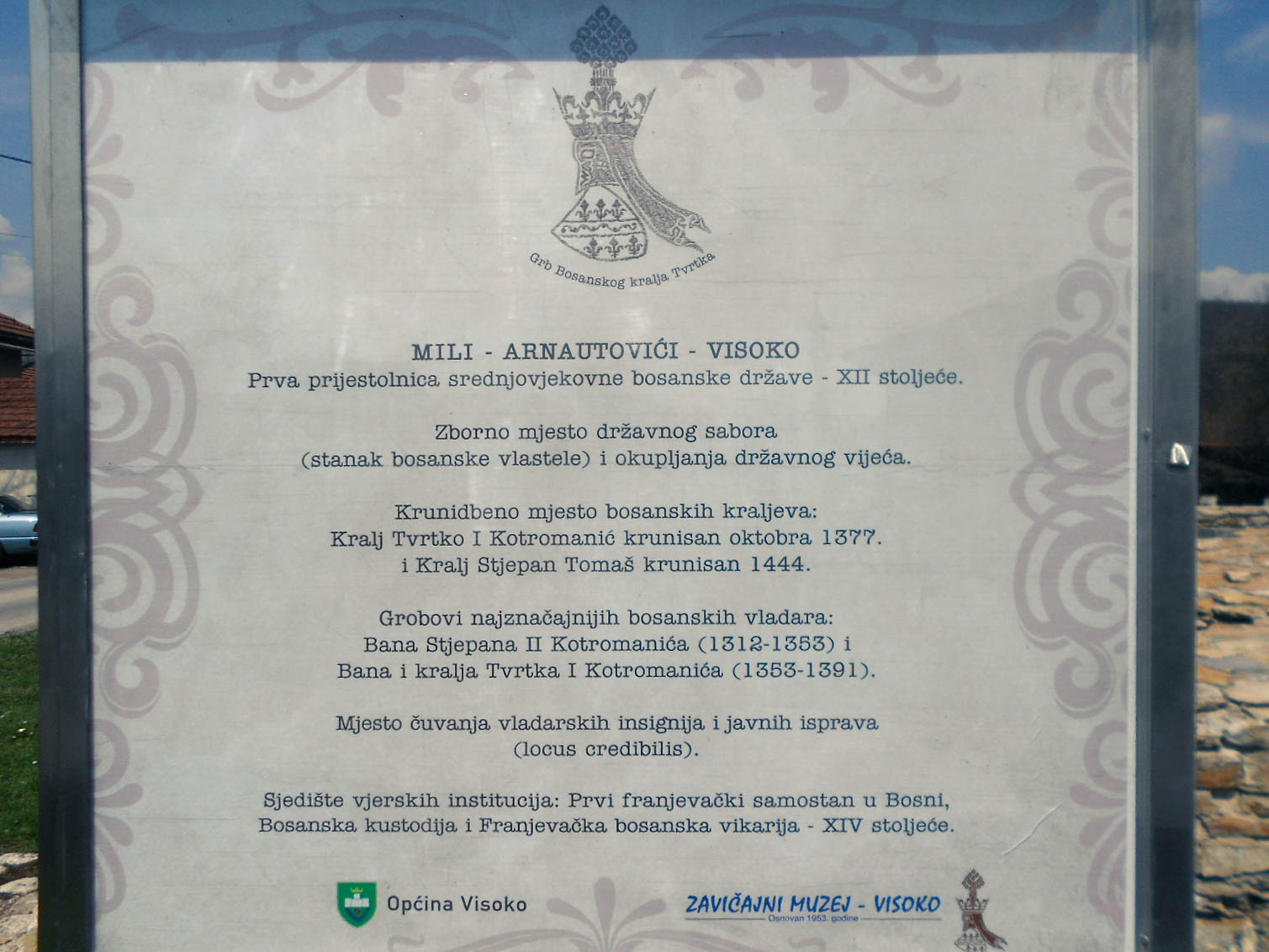

In Arnautovići, near Visoko, there is the archaeological site Mile, the church where Bosnian kings had been crowned and buried. The status of national monument was given to this location in 2003. It is one of the most important medieval locations in Bosnia. The location has been explored several times since the beginning of twentieth century.

When you go to Mile today, you will see butchered national treasures of our country; you will see vague church contours brutally squeezed between houses, cut by the railroad and the local road. You will see continuation of the agony, which lasts for decades, of the people who live in the house almost touching the church in which King Tvrtko I Kotromanić was buried. You will see ploughed fields half a meter from the church walls, in the first zone of protection of this national monument. In fact, you will get a clear picture of how much this state and my town take care of our history.

The first Franciscan monastery, built in 1340/41, after the establishment of the Bosnian Franciscan Vicary, was alongside this church. As time went by it was destroyed, until it definitively disappeared at the end of the seventeenth century. Fortunately for all the citizens of Visoko, Franciscans returned and built the monastery on another location in 1900. The St. Bonaventura Monastery was proclaimed a national monument in 2012. It consists of a monastery building with a gymnasium and seminary, accompanying the church and a part of a moveable legacy – a collection of old paintings.

During the last war, soldiers of the Army of Bosnia were housed in the Convict building. After 1995, the building was given back to the Franciscans, and students and professors, who were dislocated to Baška Voda during the war, returned. The Franciscan monastery today is a shelter of culture and education in Visoko. Their library, containing over 60,000 books, is available for all free of charge. Thanks to it, I, in addition to many other students, passed many exams, wrote term and other papers. A part of the monastery is the ethnographic collection, a collection of modern art and lapidary with exhibits from prehistoric, antique and medieval times.

The registry of prehistoric locations on the territory of the Visoko municipality was made in late nineteenth century. The biggest Neolithic site, which has been a national monument since 2006, is the prehistoric settlement on the location Okolište, in the settlements Okolište and Radinovići. Its exploration lasted five years and ended in 2007. It was concluded that it was the biggest Neolithic location in Bosnia: over 4,500 years old. If you want to go there, you should find the settlement of Okolište, which is not that hard, although there are no signs. After that you should drive to the end of the settlement (according to the instructions that I got from the people who participated in the exploration) and you will see fields – one of the fields is the place where the exploration was done. Which exactly? Well, you choose for yourself – they all look the same anyway.

Arriving at the site of the biggest Neolithic location in Bosnia, we are finishing the tour of visiting national monuments in the Visoko municipality. You should come with your own conclusion about levels of protection, preservation and promotion. Based on my experience, I can tell you that all this looks much nicer on the website of the municipality; therefore, it might be better for you not to spoil the impression by coming to the site and visiting the locations representing important pieces in the puzzle of the history of Bosnia.