Olga and Zijad will celebrate 40 years of happy marriage this year. Despite being born in Banja Luka, their wedded bliss and commitment to bringing up two daughters have not been broken by ethnic and religious divisions; not even by the war that raged in Bosnia and Herzegovina for almost four years. The key to the success of their marriage is, as they say, love, respect and compromise, above all.

The first dance

They met in the 1970s at a college disco.

“He asked to dance and that’s how it started. I wanted to teach him to dance professionally, because that’s what I do, but it didn’t work out,” says Olga with a smile.

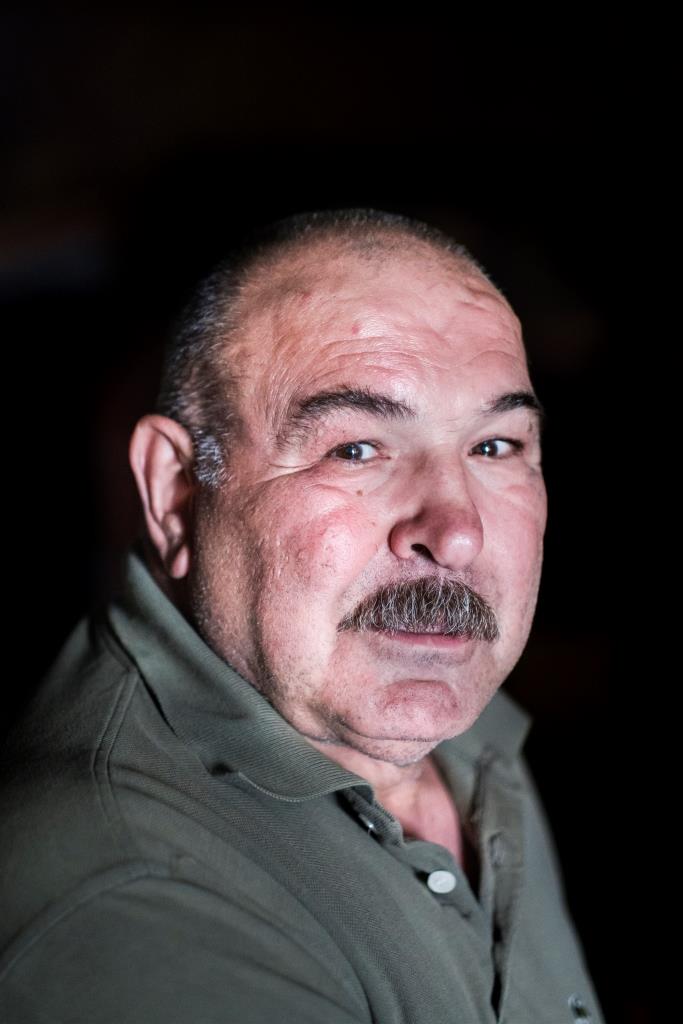

She says that her husband is reliable, protective, determined and honest – those things are the most important to her. Zijad jokingly adds that he is also a nervous person, but his wife is “honest, fair, virtuous and hardworking. Everything a woman should be.”

“She’s beautiful as well,” he says while looking at Olga.

At the time they met, being in a “mixed” relationship or marriage in Banja Luka (or anywhere in Bosnia and Herzegovina) was not unusual, not to their friends or family either.

“Nobody cared about those things. Believe me, it was nothing. When I joined the army at the age of 18, I declared myself a Bosnian. Colleagues I was with at the age of 15 are still my friends today. It’s just how real friendships work. I don’t distinguish my friends by religion. My sister is married to a Catholic. Nobody said anything to them or judged them,” explains Zijad.

Olga adds that in the city, people did not pay attention to one’s religion. “My sister is married to a Muslim. And my brother married a Catholic woman and one of our sisters was married to a Serb,” she says.

Six hundred ethnically-mixed marriages in BiH in 2019

Today, the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina is very different. In 2018, the Prime Communication Agency published a survey on BiH citizens’ views of mixed marriages. According to that survey, a total of 38.7 percent of citizens oppose this type of marital union.

According to data from the entity statistical institutes of the Republika Srpska and the Federation of BiH, there were more than 18,000 marriages in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2019. Of that number, only about 600 are ethnically mixed marriages.

Social perceptions of ethnically mixed marriages have changed significantly. Now few choose to start such a relationship. There is fear of condemnation by family, neighbors, and society as a whole. In addition to that, the difficult war legacy, including transgenerational traumas, often affect one’s choice of life partner.

They say that it was not easy for them during the war in Banja Luka. “There were awkward situations. Everyone had them, not just us. After all, it was a war,” says Olga.

“How Serbs felt in Sarajevo, we felt in Banja Luka. They are all nationalists, they are all in cahoots and filled with hatred,” Zijad added.

The absence of civic values in (children’s) upbringing and education

Olga and Zijad believe that there are few people who promote peace, coexistence, tolerance and compromise in Bosnian society because these values do not suit local leaders. But they have always tried to promote those values in their family. They raised two daughters, 37-year-old Maja and 28-year-old Melanie, on these values.

But not everything was as easy as it seemed on paper. Problems faced by most “mixed” families after the war were also present while Olga and Zijad raised their family. Their daughters were not raised to belong to any of the ethnic or religious groups.

“Melanie attended religious courses at school because she wanted a better GPA, and Maja never did. Maja was the only one in the class who did not attend those classes,” says Zijad.

“Melanie once came home and said, ‘Mom there was a chimney sweep at school and Dad has to sign this so I can attend this religious course.’ And I wondered what kind of chimney sweeps are connected to religious classes, and then I realized she’s talking about hodža [a muslim schoolmaster],” Olga recalls with a laugh.

They believe that teaching civic values is the most important thing when raising kids, but they add that those values are almost non-existent here in BiH.

“In all civilized societies, civic values come first, but in nationally-oriented societies, they take a backseat. Wherever religion comes first, there is no progress. Africa, Brazil, Uruguay, South America, all those religious countries, it’s all like ours, so there is no progress. Before, people valued one’s personality, morals, promises, honor,” says Zijad.

“Everything that is normal elsewhere is not normal here. All this that we are talking about here is never mentioned at all in Germany, for example. My brother is in America and when he applied for his first job, he said he was from Bosnia. To that, his employer replied, ‘What does it matter? I’m from Boston.’ Foreigners do not perceive ethnicity as we do in Bosnia,” says Zijad.

Everyone has the right to their own beliefs

Although they say that they are atheists, all religious and other holidays are celebrated in their house. They believe that religion is a totally private matter. Everyone should decide how they will treat religion and faith. It should not be imposed on anyone.

“Everyone has their own beliefs, and they have the right to do so. We have friends who celebrate their slavas. I never told them, ‘don’t do that,’ nor did they tell me that I should. It’s a private matter, so if you don’t impose that on me, I won’t impose anything on you,” explains Zijad.

“I even have an aversion to religion, especially nowadays. It has become a business today. Nobody does that from the bottom of their hearts anymore,” he added.

When Ziyad’s mother died, Olga said that Eid would be celebrated in their house. And everyone was always welcomed. “I’m not doing it for [Zijad]. I’m doing it for myself because I said that people can come to us on Eid. I even made baklava during the war.”

For Easter, they paint eggs and gather again as a family, only the closest family members, without much fanfare.

“Before the war, I did it for Catholic Easter, so that nobody could tell me I did it just for my Orthodox Easter, but for Catholic. Then I started celebrating everything,” Olga recalls.

Once their daughters, today a granddaughter receives gifts from Olga for Saint Nicholas Day and from Zijad for the New Year.

A society of backwards values

For almost fifty years Zijad and Olga have lived in the same neighborhood, where nothing has changed. The neighborhood has remained the same since the 1970s. They help each other, but they don’t visit one another too much.

“Things are different in urban areas. We don’t have the habit of drinking coffee with neighbors at one person’s house and then in someone else’s tomorrow. Everyone has their own things to do. My mom, for example, always went to her neighbor and she to her. That older generation took care of those relationships and visits were frequent, but back then there was more time for that,” says Zijad.

They can’t even compare times before and after the war. Everything has changed – the value system, the way of life.

“It cannot be compared to now. Before the war it was a normal society, now it is different. Our society is now a septic tank,” says Zijad.

The reason for this, he believes, is that everyone is selfish now. Normal values that existed before have been forgotten. The fact that a small number of people got rich in dubious ways, and most of the others remained poor, adds to that feeling.

“Property has changed people. It’s all about personal interests today. What suits whom. I had a Mercedes before the war…I know people who didn’t have a bicycle then and now have half of Banja Luka, and we have nothing. That is the root of the problem. Same as in Sarajevo and elsewhere. The problem is that one could finish college within two months with some strings pulled, and someone studies for five years and nothing. And it happens every day and we know it, but we do nothing about it,” says Zijad.

A life filled with happiness

That day, after the first morning coffee before our arrival, they were making a toy for their granddaughter because it was her birthday. “Then he fixed some of his machines and I helped him when he needed help with holding something and so on. Then we had lunch and that’s it. That’s how our days generally go by,” says Olga.

In today’s Banja Luka, where the demographic picture has completely changed after the war, in a society that looks at a family like theirs with prejudice, Olga and Zijad, regardless of the challenges and obstacles which life has brought them, fight through everything together. From making a toy for their granddaughter, or fixing a car, to the great task of raising daughters, their love, mutual respect, and understanding, on which they base forty years of their marriage, make their lives filled with everlasting joy.

______________________________________________________________________

Text editing: Balkan Diskurs team; Photography: Mitar Simikić; Photo Editor: Dr. Paul Lowe.

______________________________________________________________________

This story is part of the “Love Tales” project implemented by the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC) with a group of Balkan Diskurs youth correspondents. The project is implemented with financial support from the VII Academy, the BOLD program of the US Embassy in BiH, and PCRC’s core grants, with the aim of challenging the common narrative that real connections between Bosnia’s different ethnic groups are unattainable by documenting stories of successful interethnic relationships across the country.