Marta Vidal explores Bosnia’s bridges and the stories of the people who cross them, reflecting on bridges as elements of connection in a country still divided and scarred by recent war.

Of all the things created and built by humankind, nothing in my mind is better or worthier than bridges. They are more important than houses, more sacred, and more universal than temples. They belong to all and treat all alike, at a spot where most human needs entwine. — Ivo Andrić

Bosnia is a country of bridges: Sarajevo is famous for its 13 bridges, among them the well-known Latin Bridge where Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, an event that triggered the First World War. The Mostar Bridge is on the cover of almost every Bosnian travel guide, and the photos of its destruction during the war still haunt the country. Many cried for the bridge the same way they would cry for a deceased friend or family member. Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić’s book The Bridge on the Drina is an elegy to the Ottoman bridge in Višegrad, which connected the people living there.

But bridges also have an important symbolic meaning. A proverb says people fight and feel lonely because they build too many walls and not enough bridges. As an element of connection, a bridge is a beautiful symbol of intercultural debate and reconciliation, especially important in a country still divided and scarred by a recent war.

Bridges also symbolize mobility, communication, and development. They can connect people and promote understanding while allowing them to reach the “other side.” During my time in Bosnia, I discovered its bridges and the inspiring people who cross them. These are their stories.

Brisko Corda – Old Bridge in Mostar

The bridge in Mostar is a reconstruction of a sixteenth-century Ottoman bridge that was destroyed on 9 November 1993 during the war. Mostar was named after the bridge-keepers (mostari), and the old bridge, which stood for more than 400 years on the River Neretva, was an important symbol of the city. It was a meeting place and where the famous annual diving competitions were held.

Brisko was born in Mostar and lived there his entire life. He was the last person to cross the bridge before it was destroyed during the war.

“The day I crossed the bridge for the last time my family was split in two, across the two sides of the river. We could only see each other if we crossed the bridge,” Brisko recalls. On that day, one of the sides didn’t have any water, so he had to go to the river. “I was crossing the bridge to bring water to my family. When I was returning, the bridge was bombarded,” says Brisko.

On 8 November the bridge was bombarded throughout the day until it was on the verge of collapse. On the morning of the following day, the bridge collapsed after being hit by three grenades while Brisko was crossing it.

“I cannot grasp the fact that I experienced that and survived. I wonder what I did for God to save me.” Brisko remembers thinking that he would die at the bridge and fall with it into the waters of the Neretva. He ran as fast as he could, and when he reached the end of the bridge he was covered in white dust. “I didn’t have a scratch, I just looked as white as a miller,” he laughs.

But he feels a part of him also crashed with the bridge. “Not only a part of me but of all the people who were born in Mostar and felt the bridge was also a part of their lives,” Brisko says. People grieved for the bridge all over the world, receiving the news of its destruction with despair.

“We expect people to die, [but] the bridge in all its beauty and grace was built to outlive us; it was an attempt to grasp eternity. It transcends our individual destiny. A dead woman is one of us – but the bridge is all of us forever,” wrote Slavenka Drakulić, a Croatian journalist and novelist, about the destruction of the Mostar bridge.

The reconstruction work began in 1997 with support from UNESCO, and the bridge was rebuilt using the same techniques as the original. Croats and Muslims worked together to rebuild it. The official opening ceremony was held in July 2004. “When I was crossing the new bridge for the first time my legs were heavy,” Brisko recalls. “It was an unexplainable feeling.”

Today tourism plays a big part in the city, as the reconstructed bridge attracts big numbers of visitors. It remains the most important symbol of the city, and its reconstruction a hopeful sign of reconciliation.

Elvin Reezepovic – Olga and Suada Bridge in Sarajevo

Named after the first victims of the siege of Sarajevo, Olga Sučić and Suada Dilberović, the Olga and Suada Bridge was constructed after the Second World War. On 5 April 1992, a peaceful demonstration was held in Sarajevo. While protesters marched for peace, snipers aimed at the civilians and opened fire on the crowd.

“The fifth of April is the day of my birthday and it is the same day Suada got killed on the bridge. It’s a very sad day to me,” says Elvin Reezepovic, who was participating in the peace demonstration that day. “I remember seeing Suada fall in front of me. I just happened to be on the bridge at the same time; I didn’t know her,” Elvin recalls.

Suada was a medical student at the University of Sarajevo. She was in her sixth year of studies when the war started. Elvin was close to Suada when she was shot, and when he saw her lying on the floor he began to cry because people were dying in front of him. Six others also died that day. “We took her by car to the Kosevo hospital; I wanted to donate blood to try to save her, but unfortunately she didn’t make it. I still have the horrible image of her body on the bed being rolled through the hospital.”

Because of the bad memories, sometimes Elvin wishes the bridge did not exist. “Whenever I walk past it I turn around and I see the faces of those who died,” he says. But he still loves bridges. “They can connect people, cities, countries. The most beautiful stories are those of bridges.”

Another story connects Elvin to another bridge: on the 9 November 1993, a few minutes after the bridge in Mostar was destroyed, he was severely injured in Sarajevo. “That date to me is like a new birthday. I was declared clinically dead by the doctors. I was very badly injured but I managed to survive.”

Elvin was injured while fighting to defend Sarajevo, and every year on that day he goes to Mostar to visit the bridge. “I think of the bridge as almost a living being. I put my hands on it and I say, ‘You have fallen, and so have I. You have gotten back up, and so have I.’”

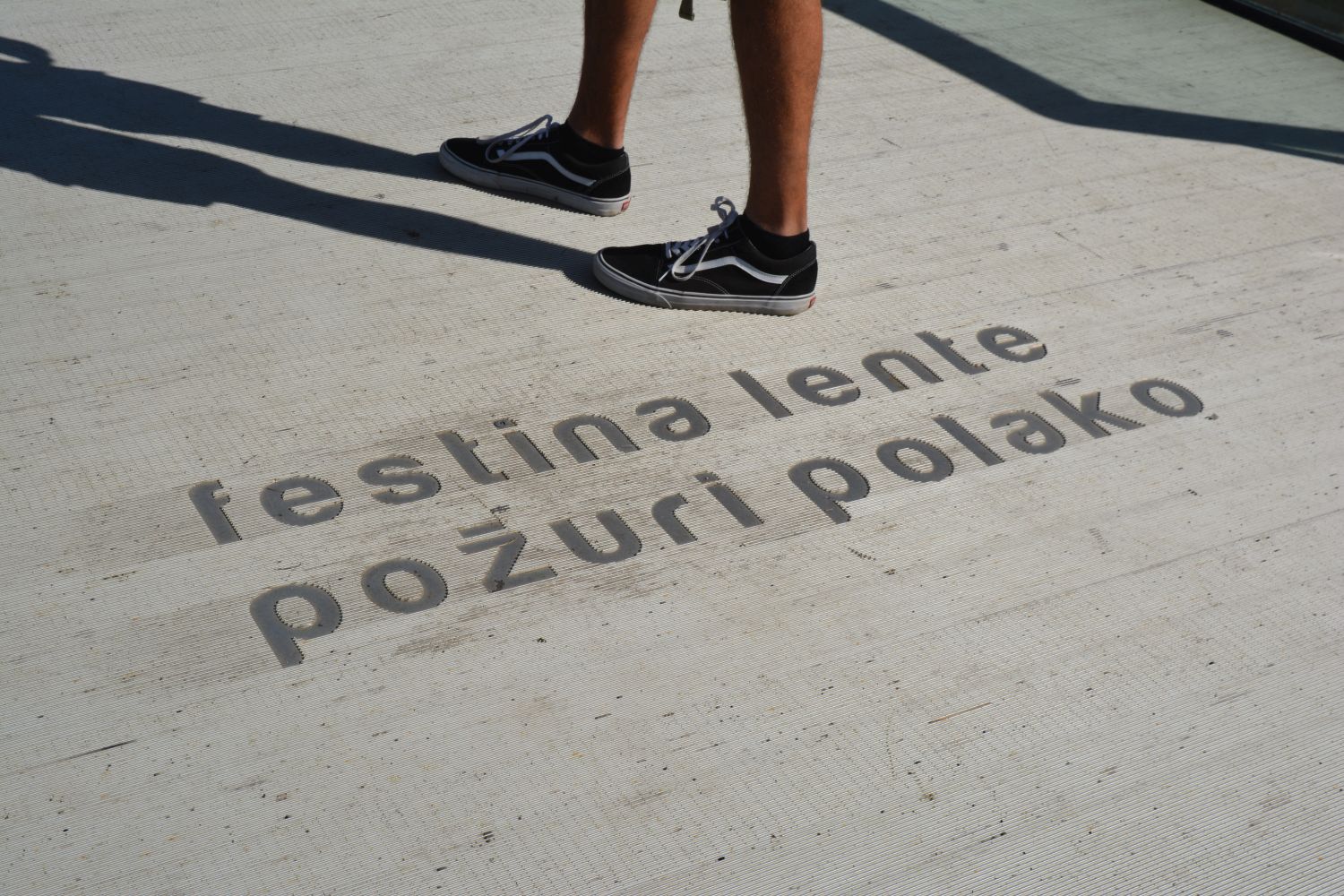

Bojan Kanlić – Festina Lente Bridge

The Festina Lente pedestrian bridge was built in 2012 in front of the Fine Arts Academy in Sarajevo. It became a landmark in the city because of its original modern design. In 2007, a contest was held to design a bridge in front of the academy. The winning project was designed by a team of the academy’s students.

Bojan Kanlić studied in the Fine Arts Academy and was in his second year when the project he did with two other colleagues, Amila Hrustić and Adnan Alagić, was selected by the jury. “I think we won that competition because we didn’t think about winning,” says Bojan. “That gave us the possibility to do something extraordinary, something totally different.”

His gravity-defying loop plan of aluminum and steel won the competition, but Bojan and his colleagues had to wait for five years to start building it due to the bridge’s unusual design.

“At first, people were against the bridge; they thought it was too modern and too ugly,” Bojan says. But he believes that “new things have to be ugly because they are different.” He now works as a teacher in the academy, and every day he sees people sitting on the benches and taking pictures. “I think our idea worked and the bridge somehow became a symbol of the city.”

The academy is located in a former evangelical church, so Bojan and his colleagues wanted to unite the secular and the spiritual. The idea to make a loop also came as a metaphor for art. “Art is something that many people see as totally upside down. Something that gives you a different perspective of the world.” So the concept was to create a gate, “a connection between the art world and the everyday world,” explains Bojan.

Festina Lente, which in Latin means hurry slowly, is, according to Bojan, a symbol of the city. “It is connected to the mentality of the people here. Time is different, people are slower. But when people are slower they also think quicker,” Bojan says. The idea was to make crossing the bridge an experience. “Of course, if you’re going too fast, you will not pay attention to the details of the architecture or the beauty of the academy.”

Bojan believes Sarajevo is defined by bridges and for him, each of them has a story. He felt honored to build a bridge in his hometown. “Bridges are very important here even if we have a small river. During the war, the city was separated by the river, and these bridges are a symbol of separation and later connection. They are full of meaning.”

Boris Gojkovic – Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad is one of the most important bridges in Bosnia. In The Bridge on the Drina, Ivo Andrić’s best-known novel, the Nobel Prize winner depicts life in Višegrad across the centuries and the stories of those whose lives revolved around the famous bridge, built in the sixteenth century by the Ottoman Empire.

“When I was younger I saw this bridge as just a simple bridge, but now I know that having monuments like this in our town is a real treasure. Because of the bridge, I realized how this small town is beautiful and important,” says Boris, who was born in Višegrad and lived there his entire life.

“This bridge has been here for 400 years, and it is a real symbol of lasting and surviving,” he says.

But the bridge also became a symbol of death. In Ivo Andrić’s famous novel, the bridge is a silent witness to atrocities being committed during the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires. During the war in the 1990s, the bridge was chosen as a place of serial public executions of Muslims, as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing. According to the ICTY, Višegrad was subjected to “one of the most comprehensive and ruthless campaigns of ethnic cleansing.”

In 1992, the bridge was the bloodiest site in Višegrad, where men, women, and children were shot into the waters of the Drina. Visible from almost every part of the town, the executions happening there were meant to be public.

The number of people killed at the bridge was so high that at the end of June 1992, a police inspector in Višegrad received a complaint from the management of the hydro-electric plant across the Serbian border. “Could whoever was responsible please slow the flow of corpses down the Drina? They were clogging up the culverts of the dam,” reported Ed Vulliamy, a journalist for the British newspaper The Guardian.

Ivo Andrić’s book was an elegy to the Ottoman bridge and the way it connected people from different ethnicities, religions, and cultures living around it. But the bridge is no longer a symbol of connection, since the memories of the atrocities committed there during the war still haunt Višegrad.

Enver Hadžiomerspahić – Ars Aevi Bridge in Sarajevo

The Ars Aevi Bridge was designed by the renowned Italian architect Renzo Piano and built in 2002 as part of the Ars Aevi Contemporary Art Museum. It was envisioned as an access point to the museum of contemporary art planned to be built next to the National Museum in Sarajevo.

The idea to start a contemporary art museum materialized on the night of 27 April 1992, as the Museum of the Olympic Games in Sarajevo was being shelled. The project emerged as a reaction against the religious and ethnic divisions during the war.

“It was insane to speak about building a museum of contemporary art in those days in which none of us knew if we were going to be alive the next day,” says Enver Hadžiomerspahić, responsible for the conception and strategies of the Ars Aevi Project.

Together with local artists and with the official support of key figures in Sarajevo, Enver invited the world’s leading artists to form the collection for a museum of contemporary art. The initiative aimed at responding to the siege and the war as an “expression of an international collective will.”

“We wanted Ars Aevi to be an international project, to be above all nationalities and religions,” says Enver. When the project started receiving donations from world-renowned artists “it was not just because the city was under siege, it was an emotional response of artists and their feelings towards Sarajevo where worlds collide and meet,” Enver believes.

When architect Renzo Piano came to Sarajevo in 1999 to the opening of an Ars Aevi exhibition, he was thrilled with Sarajevo’s bridges. “It was a rare example of a city populated by bridges. He thought it would be beautiful to build a bridge in front of the museum,” tells Enver.

Piano built the bridge himself with partners from his foundation. “The bridge is a gift of Renzo Piano to Sarajevo. When he told me about his idea to build a bridge, I said it would be beautiful. He said: ‘Of course it will, I will make it,’” Enver recalls with a smile.