It seems that I am not able to resist going back to the ruined places of my childhood. They are there to break me, to shake me; they are a part of my identity. After all, they are here only to come to life again.

Photos and text by Nevena Medić

Our ability to narrate stems from the ability to deepen our conceptual understanding of a particular place. We are always somewhere; we live in, travel to, and pass through various places. We build our stories to try to reconcile our own existence through them. Stories make places important for us and places become deep vases in which we keep and preserve our life’s narratives.

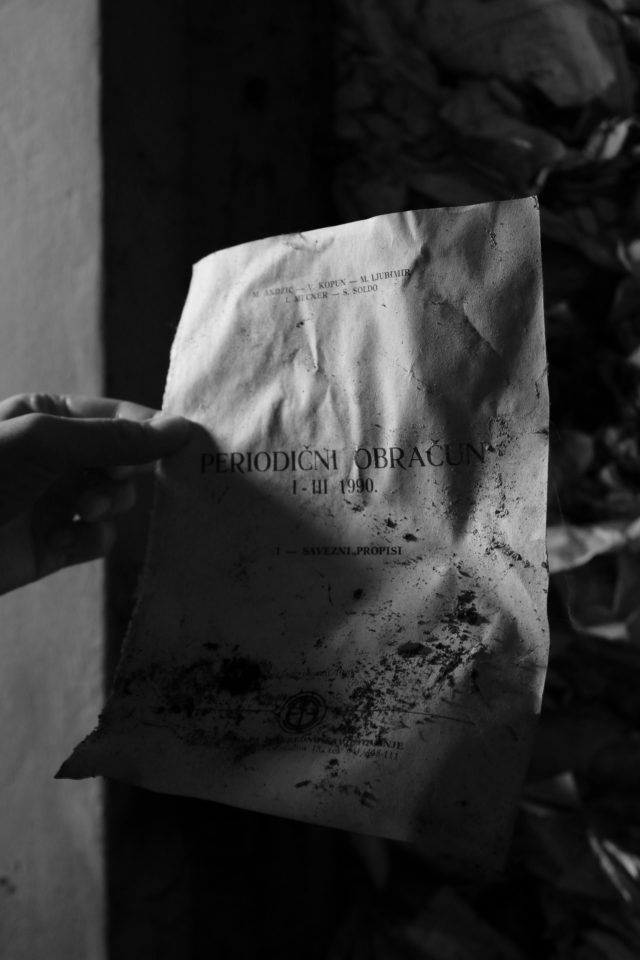

In recently demolished and destroyed areas, the essence of humanity can incomprehensible and difficult to find, but such places carry their own special tales. It is difficult to pass through destroyed hotels and abandoned and demolished houses and buildings and not think of the human hands that built these structures. The same human hands that destroyed them. It’s hard to think about this and not feel the weight of belonging to a form that was both made by the creator and, at the same time, the destroyer.

Such places and stories exist in and around every corner of Srebrenica. They make up a part of my childhood, they are still a part of my life today, and they will, in many ways, determine my future. Sometimes I have the impression that life, up until the age of six, is obscured in some locked part of our brains, a part seemingly filled with dark basements, black coal, and moisture. What happened in those years of growing up left their strange mark on me, and, every so often, as with many of life’s determinants, I end up returning to these places and stories of my past, present, and future.

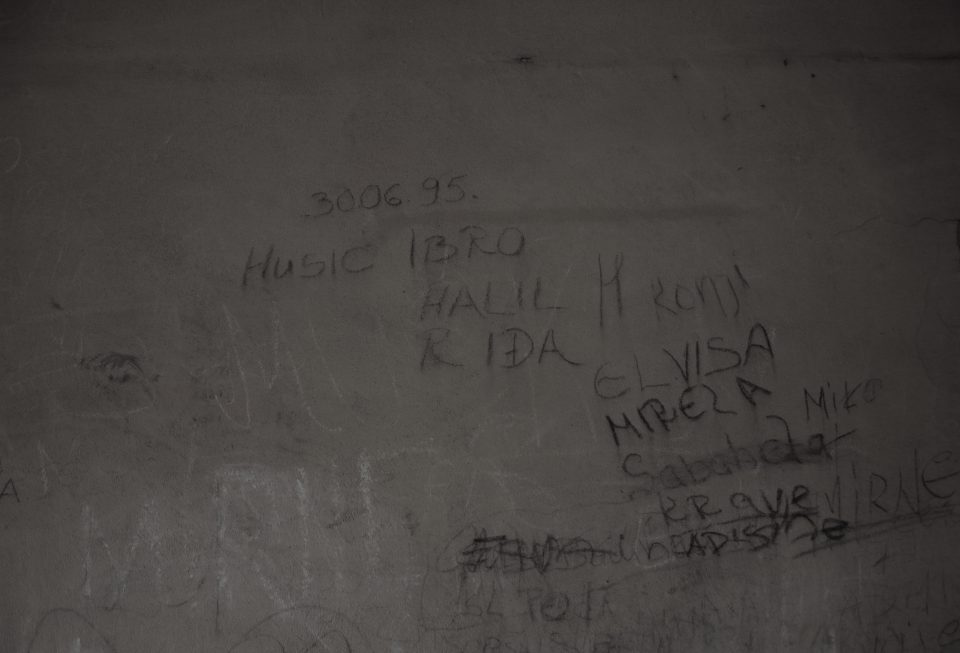

The day we left Ilijaš near Sarajevo and the day we first arrived in Srebrenica in 1996 were etched clearly into my memories. That day is brisk and returns as a brilliant flash – a reflection on the glass of my mind’s eye. The city was black and broken. The street we passed was no longer bi-directional. Garbage all around, broken armchairs on the road, beds and destroyed furniture, the path became narrow and dark. We could barely pass through it. For too long we have lived using makeshift nylons as a replacement for glass. But I was happy. The two slices of pâté, eaten while standing at the door, became the main delicacy of childhood skeletons. In abandoned lifts, we guarded the cheap footballs that we bought at the flea market. We wrote our initials on the walls of half-empty buildings, N + N, or some verse of a song from the new Nirvana album.

The expedition to deserted and destroyed houses was a paradise lost for children in the rainy days of autumn. The paradox is that we, the children born after the war, most liked to play the game of war. “Ra-tat-tat-tat” echoed across the decaying rooms of abandon. It’s as though the space had imposed its game on us, as if the war was the only thing we knew and the only thing we learned.

I lived a happy and carefree childhood. For many, it was the opposite growing up in difficult post-war circumstances, of which I was often unaware. Today, when I take a closer look, all the war and post-war occurrences were part of my identity and, a different life and childhood, I do not know of. I can’t and, sometimes, don’t want to imagine a different life and childhood.

I often walk through the abandoned places of my childhood, filled with the scent of dampness and humidity, with a dull feeling of emptiness as I recall the days of my childhood. I often think that I would like to return to this period of my life because, then, I did not know anything. I was, in some ways, indifferent. The departure from home is forgotten; all that remains are a refuge, a flashing bullet, and a mortar shell. Suddenly the main problem became whether the street light on the main street was working so that we could play late at night.

Not long ago I was given a school assignment to write a philosophy essay on the topic of “the hole in the wall”. I started by borrowing from Anna Karenina and adjusting it for the purposes of my essay: “All the holes in the wall look alike, only this particular hole in the wall is sad in its own way.” At the end of the essay, my hole in the wall took a more human form.

During the refugee period in New Belgrade, a man with a smirk approached to convince me that a higher celestial power was operating the lifts. He told me that somewhere up there, at the edge of the world, a group of people is constantly working to operate the lifts. I was fascinated. When I first saw this machine in the abandoned Domavija Hotel in Srebrenica, I thought the man had deceived me. But then I thought, “It doesn’t matter,” because Mama deceived me by saying that we would never leave Ilijaš and that my toy cupboard would arrive in another truck.

30 June 1995. Signatures in the Domavija Hotel shelter – even the walls remember. They remember the ones that are maybe no longer with us, those who have been permanently deceived for all time.

It seems that I will not be able to resist going back to these stories and places. They are there to break me, to shake me, and to make me face everything. After all, they are here only to come to life again.

The Balkan Diskurs Youth Correspondent Program is made possible by funding from the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).