From May 28th to August 21st, 1992, over 3,000 Bosnian Muslims and Croats were confined, tortured and killed at the Omarska camp in entity of Republika Srpska. Despite the extent of the atrocities committed at Omarska, the former camp pointedly lacks any form of memorialization as a result of entity of Republika Srpska’s enduring war crimes denial. This marks a symbolic continuation of genocide, perpetuating survivor’s trauma and impeding efforts towards reconciliation.

“All may be fair in love and war, but practices such as those at Omarska were the most perverse forms of physical and psychological torture – a military enforced prostitution of people, supplied by a huge arsenal of pain and suffering”. – Rezak Hukanović, The Tenth Circle of Hell. (Hukanović, 1996)

In his book The Tenth Circle of Hell, Rezak Hukanović reflects upon his time as an inmate at the Omarska concentration camp, where over 3,000 Bosnian Muslims and Croats were confined, tortured and killed between May 28th and August 21st, 1992. His words are as relevant now as they were in 1996. They serve as a reminder of the depravity into which humankind seems capable of sinking.

The genocide and war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina continues to be denied, relativized and glorified. Efforts to institutionalize its remembrances have been slow, though this year has brought renewed hope that this could change.

On May 23, 2024, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution on the genocide in Srebrenica, declaring July 11 as the International Day of Remembrance of the Srebrenica genocide in 1995. This marks a significant step towards commemorating the genocides and other crimes committed during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Though this marks progress towards reconciliation, other sites around Bosnia and Herzegovina where similar atrocities were perpetrated have not received the same degree of acknowledgment. The Prijedor region in particular was the site of several concentration camps, but has suffered since the end of the war from a lack of acknowledgment of the atrocities committed against non-Serbs.

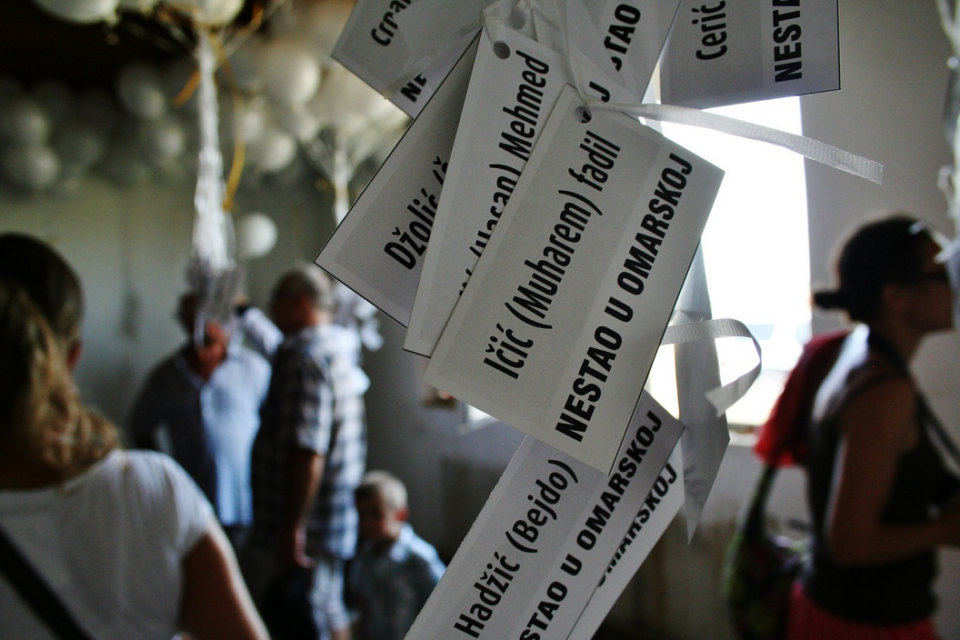

More than thirty years later, survivors of the Omarska camp continue to be denied the essential right to commemorate their suffering. The Republika Srpska’s dismissal of any kind of memorial at the Omarska mines continues to retraumatize survivors and the families of victims. This also marks an impediment towards the peacebuilding process at stake.

The memorialization processes that have been implemented at Srebrenica need to be replicated in regards to the atrocities committed in Prijedor, and, specifically, in the case of Omarska. The practice of restricting memorialization is a symbolic continuation of genocide, meant to further persecute those who survived the war.

Omarska and the Power of Memorialization

To understand the importance of memorialization’s power, one needs to understand the basis of genocidal intent. According to Dr. Hikmet Karčić , genocide is an attempt to break down the collective identity— or, “Family of Mind”— of a particular group. As Karčić reflects in Torture, Humiliate, Kill, “camps have, in many places around the globe, served as places of terror and torture, designed to create deep, long-lasting traumas that not only break the individual but break the individual’s ‘family of mind,’ their connections with others, their community, their culture, their memory, and their past and future” (Karčić, 2022). Genocide encapsulates a variety of acts with the aim to destroy, in whole or in part, a community. This intent can lead to the utilization of multiple means of destruction, from physical to psychological (Article 6, Rome Statute).

While Omarska was not a de facto death camp, the crimes committed during the few months it was in operation are marked as some of the most extreme examples of violence in the Bosnian War. While other concentration camps around the world have had higher death tolls, death is not the definitive mark of genocide, but rather the final component of the destruction of a particular group. As journalist Peter Maas reflects, “It [Omarska] was not a death camp on the order of Auschwitz. There were no gas chambers to which the prisoners were marched off every day. What happened at Omarska was dirtier, messier. The death toll never approached Nazi levels but the brutality was comparable,” (Karčić, 2022)). While mass murder is concretely measurable, one should not minimize the extent to which symbolic dehumanization— which is often difficult to quantify— was key in the genocidal plan of the Republika Srpska authorities.

Severe dehumanization tactics were wielded over inmates at Omarska to degrade both their humanity and collective identity as Bosnian Muslims and Croats. Through the breakdown of identities, Serb forces were able to carry out a campaign of violence which culminated in the repossession of historically mixed cities and towns. The Bosnian Genocide, including those crimes which were committed at Omarska, utilized symbolic and physical tactics to dehumanize inmates, thus marking an effort to break down their “family of mind.”

Torture, Sexual Violence, and the Fragmentation of Collective Identity

In his memoir The Tenth Circle of Hell, Hukanović reflects upon the torture he both witnessed and experienced as an inmate at Omarska. Prisoners were often forced to inflict violence on each other, with the looming threat of physical torture against themselves if they did not comply. At one point, Hukanović recounts a memory in which Serb authorities forced a Muslim prisoner to bite off a fellow inmate’s genitals. He was threatened with physical violence if he did not comply. This scene goes beyond the physical violence of genocide— the mutilation of one’s genitals takes on a symbolic dimension, a forced castration that leaves the prisoner unable to reproduce. As articles 6b of the Elements of Crimes stipulates, Genocide can also happen “by causing serious bodily or mental harm”. Through such acts of sexual violence – and the trauma resulting from it – the perpetrators intended to destroy a chosen group, here the non-Serb population, by taking away their capacity to reproduce.

Such a mechanism was also replicated through acts of sexual violence against women. Though women were a minority in the Omarska camp, it is estimated that around 37 women passed through the mines, where they were routinely sexually abused by Serb guards (Vulliamy, 2012). Sexual violence becomes a weapon through which a genocide can be committed because it inflicts severe physical and psychological trauma on the targeted population. Acts of sexual violence enabled Serb guards to lay claim to their inmates’ bodies. The systematic rapes and sexual assault used by the perpetrators instilled fear, a profound sense of humiliation as well as dehumanization within the victims, thereby breaking the spirit and cohesion of the community. Causing this specific type of bodily harm completely undermines the community’s ability to sustain itself, therefore aligning with the broader genocidal intent to destroy a specific group.

This logic was especially palpable at Omarska, where the sudden, sporadic nature of the torture inflicted upon inmates enabled psychological torment that broke down prisoners’ identities. Moreover, as neighbors and families were imprisoned at Omarska alongside each other, this had a definitive role in the breakdown of social bonds among the community, effectively breaking down inmates’ “family of mind”. Sons were left to care for their ailing fathers, community doctors took on the role of caring for camp victims with makeshift medical supplies, and women working in the canteen risked their lives to smuggle food for starving inmates (Hukanović, 1996). Individuals’ livelihoods and identities thus became altered during the war, resulting in broken trust among former neighbors following the end of the conflict. Those who survived the camps become incapable of divorcing their memory of Omarska from those who they were tortured by, effectively breaking down the strong community dynamic which had existed before the war.

Denial as a Later Stage of Genocide

While physical and verbal dehumanization occur simultaneously in genocide, symbolic dehumanization processes can persist in the form of genocide denial as well as the obstruction of any memorialization. In this way, the genocide cannot be said to have ended once the physical torture ceased. It is perpetuated by the lack of accountability towards the perpetrators of the genocide and the institutional denialism in the Republika Srpska entity.

Restricting the process of memorialization and honoring of the dead is a powerful symbol of the denial process at play but also of the denial of the humanity of all the victims. As Ed Vulliamy explains, “it is among mankind’s most primal urges to commemorate the dead with physical objects, monuments, headstones or simply mounds of earth. The erection of markers for the dead is as ancient as Homo sapiens, (…). Monuments to the dead are formative to the complex human process of mourning, and to deny them or obfuscate around the right of the bereaved to erect them is anti-elemental, destructive at a deep historical and mythic level” (Vulliamy, 2012). The scarcity of elements marking Omarska is a way to deny this primal need of all to grieve properly.

This specifically applies to the Omarska case, where “the buildings where the camp was located cannot be approached without special permission from ArcelorMittal. You can approach the camp, where there is a sign that filming is prohibited, and in the distance you can see several buildings belonging to the mine, but there is no indication of what happened there in mid-1992.” (https://kulturasjecanja.org/en/prijedor-omarska-camp/)

In 2004, the rights to reopen the iron mine which housed Omarska were acquired by a Brit, Lakshmi Mittal. The repossession of the mine prompted activists to confront the enterprise, calling for a monument to be built on the mine’s grounds. Mittal listened to the call for commemoration, and accordingly drafted plans for a physical memorial to be built (as well as the preservation of one particular site of mass torture, Omarska’s “White House”). At first, Mittal agreed in 2005 to finance a memorial on the site of Omarska. Despite this, fundamental disagreements over the form of the monument marked challenges to its construction. Ultimately, pressure from the Republika Srpska authorities prompted the memorial to be abandoned. Today, there exists no memorial at Omarska, and no concrete plans for the establishment of one anytime soon. Not only has the development of the memorial been frozen, but since 2012, victims have been denied access to the site, allegedly for safety concerns. This further drowns out the victims’ experiences within the camp.

What happened at Omarska, and within the camps of the Prijedor region in general, can only be known by a well-informed public. Transforming rape camps into Spa Hotels (Vilina Vlas), or simply by putting pressure on local organizations to make sure memorials are not built, the RS authorities actively foster a culture of denialism. As a result, those who are not acquainted with the history of the camps cannot be aware of the atrocities committed there. This lack of acknowledgement consequently minimizes the cruel reality of the survivors’ experiences. Memorialization has many layers, from collective remembrance, to a more individual sense of relief. For the survivors, “a memorial to Omarska camp would be a far more useful and locally relevant initiative than the distant war crimes process – ‘a fantastic opportunity to tackle the past’” (Sivac-Bryant, 2016). More than thirty years after the war, confronting the region’s past is still a source of conflict and denial.

Blocking the possibility of acknowledging the concentration camp legacy of the Omarska mines not only buries the atrocities committed, but also has a negative impact on the peacebuilding process at stake. In order for peace to be built, a nuanced historical narrative must emerge, one that truly encompasses the suffering of all victims. Memorialization is not just a healing process for the victims and a way to gain back the humanity that was stolen from them, but also a way to reconstruct a peaceful society. Peacebuilding relies on sustainable peace, which is built by addressing the root causes and symptoms of conflict. It aims to prevent the recurrence of violence by fostering reconciliation, rebuilding social infrastructures, and ensuring justice and accountability. Memorialization then becomes more than just a healing process for the victim, but a vital step towards the recovery of a society.

All communities involved need to participate in order for a common narrative to emerge – a historical rendering of the events of the war that all communities across a region can accept. Only from such a common enterprise can we hope that future generations will never reproduce the horrors committed at Omarska and all other camps. The 2024 UN Srebrenica resolution is another gesture towards this progress. However, peacebuilding requires acknowledgment of all the atrocities committed during the genocide. The lack of memorialization and denial surrounding Omarska and all the other camps throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina is a reminder of the crucial importance of memory for all.

—————-