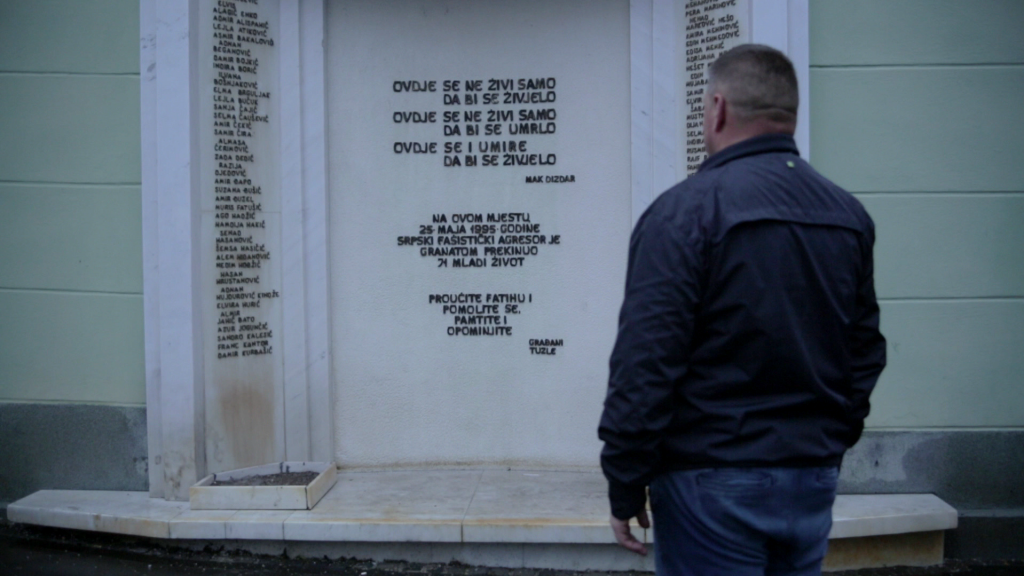

Although 22 years have passed since the shells were fired from Mount Ozren into the downtown area of Tuzla known as Kapija, the victims’ families are still waiting for justice. During the massacre, the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) killed 71 and wounded more than 140.

Although 25 years have passed since the shells were fired from Mount Ozren into the downtown area of Tuzla known as Kapija, the victims’ families are still waiting for justice. During the massacre, the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) killed 71 and wounded more than 140.

Novak Đukić, the former commander of the VRS’s “Ozren” Tactical Group, has fled to Serbia for medical treatment and his defense has requested a retrial before the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). A statement released by court officials responsible for sentencing Đukić to 20 years in prison for the crimes committed in Tuzla, declared: “The decision on this request is still pending.”

In October 2015, BiH submitted a request to Serbia to accept the verdict and to send Đukić to prison in Serbia to serve his sentence. The Higher Court in Belgrade, however, has repeatedly delayed proceedings on the recognition of the verdict due to Đukić’s poor health.

So far, only one person has been held accountable for the 71 lives lost, but, due to legal technicalities, that person remains at large.

The victims’ families have repeatedly approached investigating authorities with the names of those connected to the shelling of Tuzla’s downtown area, Kapija, but, according to the parents of the murdered children, their efforts have amounted to nothing.

“There were seven people from the VRS squad responsible for firing the shell on that fateful night. Their names were published in the media, we delivered them to the investigative authorities, but it’s as if we never did,” says Arif Ahmetašević, whose daughter Edina was killed during the shelling. Ahmetašević was also once a member of the Commission for the Civilian Victims of War.

The Prosecutor’s Office told the victims’ families that they had tried to go after those identified before later announcing that they had been unavailable for investigation.

“They allegedly looked for them. We were told they were in Serbia and that they had assumed new identities,” Ahmetašević adds.

Đukić was tried in BiH for crimes against civilians, one of the most heinous crimes of the war in Bosnia.

In January 2014, the Constitutional Court of BiH upheld the appeal of Novak Đukić, ruling that both the Constitution of BiH and the European Convention on Human Rights had been violated, thereby quashing the verdict of the Court of BiH, which, on 6 April 2010, sentenced Đukić to 25 years in prison.

The 2010 verdict was overturned by the Bosnian Constitutional Court because instead of applying the Criminal Code of former Yugoslavia during his trial, which was the code in effect during the time Đukić committed the crimes for which he was charged, the 2003 Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina was retroactively applied.

The Case is Closed

For the parents of the murdered children, this was all just a legal farce and a political compromise.

“Đukić’s verdict put an end to the ‘Kapija’ case. Everyone is satisfied except the parents. He lives in freedom, better off than all of us whose children have been murdered. I’m afraid of an even worse scenario, which is that the Court in Belgrade will acquit him completely. It’s all just politics and deals. It is my right to suspect that, as the parent of a murdered child. Is it not shameful that the parents must take the lead to provide evidence and archival materials to the investigation?” wonders Hilmo Bučuk, whose daughter Lejla was killed.

The average age of those killed and wounded was 23 years old. But the youngest victim, Sandro Kalesić, was only three. The boy, whose parents were celebrating their anniversary, was killed in his father’s arms. A piece of shrapnel hit him directly in the heart.

“It was our wedding anniversary. We hadn’t planned on going out that night because I was supposed to go to the hospital for a checkup. Still, we headed for Kapija where we intended to buy sandwiches and drink some juice. Sandro did not want to get out of the car for nearly an hour and a half. He liked to sit in the car and play with the steering wheel. Together, we entered the cafe and, just minutes before the grenades fell, we moved into the garden,” recalls Dino Kalesić.

Dino remembers how the celebration of his wedding anniversary on a beautiful, sunny day, was interrupted by a horrific explosion.

“Suddenly there was a horrific explosion. Dust was all around us. A terrifying image. I looked at Sandro. He just held his hand on his ear and sobbed. I just thought it was the fear. He probably never even knew he had been hit. I grabbed him and went into the neighboring building, fearing another round of shelling. I put him on my chest and only then did I feel the blood that had seeped through his shirt. Only one small hole, like a grain of rice. We ran to the car and rushed to the hospital. I think he died just as we passed through the hospital gates. Doctors tried resuscitating him, but it was all in vain,” says Kalesić.

That Thursday, 25 May 1995, has also remained etched in the memory of Asim Hadžiselimović. After days of heavy rains, there appeared a day bathed in sunlight. It was a day different from any other, and one that, unfortunately, will forever be inscribed with black letters in the annals of the city.

Cries, Moans, Screams

“No words exist to describe what happened. Until that moment, we were all cheerful and happy to see each other. After the blast and the flash, all you could hear was crying, moaning, screaming… My right leg was hit by shrapnel and my friends Nenad, Ago, Alem and Azur were killed not far from a parked Zastava 101 car, and, a bit further from them, Ivana, Lejla and Selma were also killed… I managed to crawl some 10 meters further and hide in a passageway because I was expecting a second explosion,” Hadžiselimović recalls.

The surviving young men and women started helping the wounded and taking them to the Gradina hospital. Asim Hadžiselimović was taken to the Tuzla hospital in a Škoda Favorit.

“A father came looking for his son and I was transported in his car together with several other dead and wounded. I talked to some who later succumbed to their injuries at the Gradina Hospital. I remember talking to Garo and Munje, but, unfortunately, they later died. My godfather Čili was with me the whole time and I can still hear the doctor saying that there was nothing they could do to save my right leg and that they would have to amputate,” says Hadžiselimović. After many years of treatment in Denmark, doctors managed to save his leg.

Only three months after the tragedy in Kapija, Arif Ahmetašević, a member of the Army of BiH and father of Edina who was killed that day, was part a unit that captured a group of VRS soldiers stationed at Ozren, the mountain from which the artillery shell was fired on Tuzla.

“This was in August 1995. I acted humanely and rationally, even though many people later asked me how I was able to remain calm. I only asked the soldiers whether they knew anything about the shelling. They told me that they hadn’t been on duty that night. Allegedly, they had only heard about the Kapija massacre,” Ahmetašević recalls.

Ten years later, Ahmetašević was recognized as the 2005 International Humanist and awarded the Golden Charter “Linus Pauling” with Plaque and Golden Badge by the International League of Humanists from Graz. The Citizen’s Association “Front,” an organization dedicated to the protection of human rights and the fight against state torture, also appointed him as an honorary member in 2008.

He says that, still today, he would repeat his actions, although his faith in justice is lost.

“I don’t think justice exists and I don’t believe the parents of these murdered children will ever live to see it if it does. I have lost faith in the justice system, and I don’t believe in courts or this country,” he says.

The victims of the Kapija massacre:

Suzan Abdulismail, Edina Ahmetašević, Elvis Alagić Enko, Admir Alispahić, Lejla Atiković, Asmir Bakalović, Adnan Beganović, Damir Bojkić, Indira Borić, Ivana Bošnjaković, Elma Brguljak, Lejla Bučuk, Sanja Čajić, Selma Čaušević, Amir Čekić, Samir Čirak Ćiro, Almasa Ćerimović, Zada Dedić, Razija Djedović, Amir Đapo, Suzana Dušić, Amir Đuzel, Muris Fatušić, Ago Hadžić, Hamdija Hakić, Senad Hasanović, Šemsa Hasečić, Alem Hidanović, Nedim Hodžić, Hasan Hrustanović, Adnan Hujdurović, Elvira Hurić, Almir Jahić, Azur Jogunčić, Sandro Kalesić, Franc Kantor, Damir Kurbašić, Vanja Kurbegović, Vesna Kurtalić, Sulejman Mehanović, Pera Marinović, Nenad Marković, Amira Mehinović, Edin Mehmedović, Edisa Memić, Adrijana Milić, Nešet Mujanović, Edin Mujabašić, Samir Mujić, Elvir Murselović, Šaban Mustačević, Dijana Ninić, Selma Nuhanović, Indira Okanović, Rusmir Ponjavić, Raif Rahmani, Fahrudin Ramić, Nedim Rekić, Jasminko Rosić, Nihada Šišić, Armin Šišić, Senahid Salamović, Edhem Sarajlić, Jasminka Sarajlić, Aim Slijepčević, Savo Stjepanović, Jelena Stojičić, Ilinka Tadić, Azur Vantić, Mustafa Vuković i Adnan Zaimović.