In 2011, peaceful protests started in Daraa, Syria following a wave of large-scale protests across the Arab world. Bashar al-Assad’s regime brutally cracked down on all opposition to his rule and met protests with violent repression.

In 2011, peaceful protests started in Daraa, Syria following a wave of large-scale protests across the Arab world. Bashar al-Assad’s regime brutally cracked down on all opposition to his rule and met protests with violent repression. While repression and detention are by no means a new phenomenon in the reign of Bashar al-Assad or his father, Hafez, it has been seen on an unprecedented scale throughout the Syrian war. Six years on, a recorded 470,000 people have died and more than 117,000 have been detained or have disappeared, largely at the hands of regime forces.

In the last five years, the Islamic State (ISIS) has stolen the Western headlines with regard to the Syrian war and regime detainees have been put on the sideline. This year during the annual War Art Reporting and Memory (WARM) Festival in Sarajevo, attendees had the chance to view Sara Afshar’s documentary Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad. The film brings attention to the 117,000 detained or disappeared, including 2,000 children and the 300 a month who die in clandestine detention. It offers unprecedented access to survivors of detention, families of detainees and the dead, regime defectors and international war crimes investigators fighting to bring their cases against the Assad regime to justice and to have their stories heard.

Afshar’s film exposes the viewer to the terrifying reality of life inside the Assad regime’s detention centers, and the impact these centers have on the families of the detained. Images smuggled out of Syria by a regime defector, known as the Caesar photos, reveal the unimaginable conditions suffered by detainees: eyes gouged out, rows upon rows of skeletal remains; bodies covered with the dark blue bruises and bloodied scars of torture. Families of the disappeared search through the images, wondering if they will discover the fate of their loved ones. Not knowing what has happened to family members, if they are alive or dead, is a torture all its own for detainee’s families who remain on the outside. Many of the detainees in the photos have suffered dramatic weight loss or disfiguring facial injuries, making it a horrific and uncertain task for families to identify them. From the 53,000 smuggled images, Mariam Hallak identified the corpse of her son, Ayham, a young aspiring dentist. She keeps a photo of his bloodied corpse on her phone. Despite not knowing the whereabouts of his body, the photo provides her with closure, something so many the detainees’ families are yet to receive.

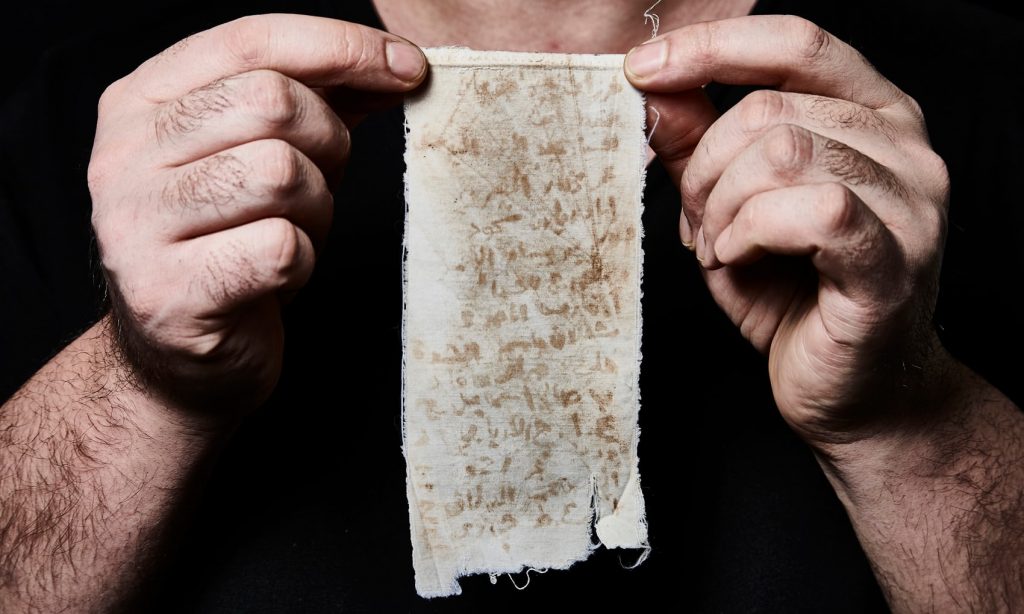

Mansour al-Omari, a journalist and human rights activist, was released from forced detainment in May 2012. He explains the lengths he went to in order to share the fate of those he left behind with their families. Upon his release, he bravely smuggled out the names of detainees, scribed in blood and rust on scraps of cloth stitched into his shirt.

Despite the horrors exposed by the Caesar photos, not been much recognition has been achieved for detainees. Mazen Alhummada, a left-wing activist and employee of an oil company who was detained for 18 months, is dedicated to changing this reality. After relocating to Europe, he promised those he left behind that he would expose the scale of the regime’s crimes.

Pursuing legal action against the Assad regime has been difficult to achieve. The UN Security Council draft resolution to refer Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC) was vetoed by Assad allies China and Russia. The first criminal case accepted by a European court against President Assad’s security forces is being pursued in Madrid, Spain by the victim’s sister, a dual Syrian-Spanish national, living. Her brother disappeared in Damascus in 2013 and, through the Caesar photos, she later discovered that he was kidnapped, tortured and murdered while being illegally detained by the Assad regime. Lawyers acting on her behalf argue that she is the victim of her brother’s forced disappearance, torture, and execution, and, because the plaintiff holds Spanish citizenship, the Spanish courts have the jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute the case.

Since the uprisings against the rule of Bashar al-Assad began in 2011, it has been not only difficult but also extremely dangerous for foreign journalists to venture inside of Syria’s borders. We have heard many competing narratives from the regime, citizen journalists, and jihadists alike. Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad provides an opportunity for the stories of those who have suffered behind regime bars to be officially entered into the long and twisting narrative of the Syrian war, and this can, perhaps, offer one more avenue along the road to justice for the victims and their loved ones.

—

The Balkan premiere of “Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad” took place during the 4th annual War Art Reporting and Memory (WARM) Festival in Sarajevo from 28 June to 2 July 2017. Organized by the WARM Foundation in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), the WARM Festival brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.