This is the story of four individuals who are taking action to create positive change for those living with hearing, vision, and mobility impairments in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The disabled face discrimination and other various challenges on a daily basis, but many have chosen to face those challenges head-on and advocate that the most difficult obstacles are those that exist within your own mind. This is the story of four individuals who are taking action to create positive change for those living with hearing, vision, and mobility impairments in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“I am a child of deaf parents, so sign language is my native language – I learned it growing up with my parents and can’t even remember the first time I began using it. Living and growing up in the world of silence has given me enormous wealth, including the knowledge of sign language,” says 25-year-old Berina Čorć from Zenica.

In an interview with Balkan Diskurs, Berina explained that growing up with deaf parents is not at all easy since the roles of child and parents are often reversed – the parents need the child to help them and interpret for them, especially in public institutions.

Based on her parents’ experience, Berina believes that persons with special needs are not given sufficient opportunities in education and employment. “My parents completed primary and secondary school and it is unfortunate that many deaf people go into the same jobs, which are very limited. Men are mostly mechanics, auto body painters, shoemakers or house painters, whereas women are either seamstresses or work at a printing shop. It doesn’t matter that deaf persons have the desire to learn new skills both at the high school and university level; the institutions just don’t have the capacity to provide this currently. The very fact that they cannot go to a high school of their choice speaks volumes about the aggravating circumstances they also face in the area of employment,” says Berina.

For these reasons, Berina decided to become an interpreter, volunteer, and activist. She soon found out that the Law on the Use of Sign Language, which was passed in 2009, is just a “piece of paper”.

When asked whether she believes the status of the hearing impaired is improving, she spoke about their need for sign language interpreters, for whom they typically must pay for out of their own pockets and often with their welfare money.

“It is appalling that the amount of social assistance they receive is not enough for them to pay for an interpreter and the attitudes towards and treatment of this marginalized group constitutes a violation of their basic human rights,” says Berina.

Berina is dedicated to improving the status of the hearing impaired and has started a Facebook page called “Kindness is a language the deaf can hear and the blind can see”. In the beginning, the page was only intended for her closest friends who wanted to learn sign language. However, she was soon surprised by the considerable interest of other people who began sharing her content and by the numerous messages she began receiving from hearing impaired people as well as from parents of hearing-impaired children who wanted to improve their communication skills.

“I am happy that so many people want to learn sign language because that suggests that people are slowly becoming aware of the existence of deaf people and their way of life,” expresses Berina.

The Other Side of the Story

Ira Adilagić, the author of the blog series “The Other Side of the Story”, which aims to raise awareness about the situation and rights of people with disabilities, believes that persons with disabilities can significantly enrich and contribute to the development of society in numerous ways. One of these ways is through the sharing of their experiences to promote social inclusion.

When it comes to education and employment, Ira believes that disabled people face the same problems as everyone else, but with the added burden of prejudice and inaccessibility. “Creating the necessary conditions within mainstream education to facilitate working with students with disabilities is invaluable because inclusion in education means inclusion in society,” she says.

According to Ira, there are many challenges for a hearing-impaired person who is learning a foreign language. She states that, luckily, the rule for Bosnian is: “Write like you pronounce, read as it is written”.

She explains that for English, however, this rule does not apply and that you must devote more time and effort to learning the correct pronunciation of each word and to be able to recognize those words through lip-reading.

Although Ira is aware of the many obstacles that persons living with disabilities must still overcome, she believes that there has been significant progress regarding the rights and social status of this marginalized group since the establishment of the disability movement.

Offering Support

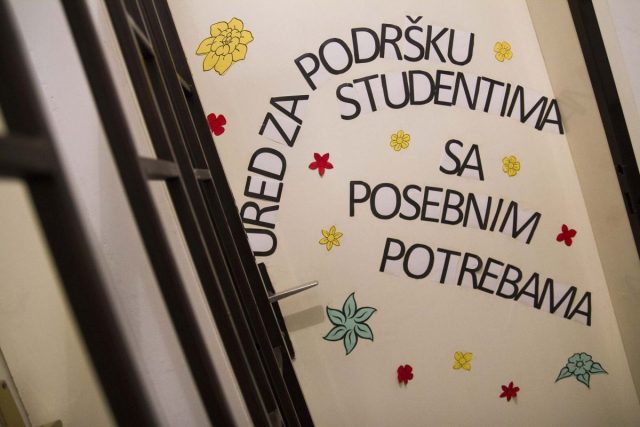

When it comes to education, the Office for Students with Special Needs in Zenica believes that change is possible.

Office Coordinator Azemina Durmić explains that support for students with special needs is categorized using three models: counselling and educational support, tutoring and note-taking assistance, and the provision aides who assist with services such as escorting the students to and from school, help with the use of assistive technology, help with the preparation of school assignments, and help with the rental of available equipment and materials. “We provide various types of support to students with special needs as they plan their studies and as they implement those plans. We also offer support to help them with their daily activities and in situations where certain difficulties might arise,” she explains.

In 2012, Azemina had the opportunity to visit the University of Alicante’s support center for special needs students whose main objective is to accommodate those with vision, hearing, and mobility impairments. She notes that the approach used by the Zenica Office has been partially modeled after those used by Alicante University as well as the University of Economics and Business in Vienna and KAHO Sint-Lieven in Gent.

Azemina stresses the importance of such visits and warns of the current situation within universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “These study visits were extremely important in providing insight into contemporary models of support. However, Bosnian universities, and Bosnian society as a whole, will have to work hard to reach the levels of support that are provided at these universities. This is especially true regarding the design and the accessibility of the dorms, faculty departments, and classrooms,” says Durmić.

Eliminating Barriers

“Persons with disabilities have to pay attention the practical things, but that shouldn’t be our only job. But in Bosnia there are less and less potential opportunities for everyone, especially for young people,” says Jasmin Dzemidzic, a disabled stand-up comedian, or, as he calls it, a sit-down comedian.

During his performances, Džemidžić uses humor to draw attention to the plight of persons with disabilities and points to the fact that although art should be inclusive, persons with disabilities often face various obstacles, which leaves them outside of the artistic mainstream.

Even though he had always wanted to be an actor, many obstacles prevented Džemidžić from graduating from the Academy of Performing Arts

“Well, I can tell you that I did not choose humor, humor chose me. I always wanted to be on stage, to act, to play big roles. My childhood dream was to graduate from the Academy and become a professional actor. It was that dream that led me to the comedy scene and, lo and behold, here I am today. It also doesn’t hurt that I have always been a very positive person and that I’ve always made my friends laugh. So, when the time came, I just moved to a bigger audience,” says Dzemidzic.

However, what Džemidžić believes is most important is “to eliminate the barriers in people’s minds”, and he hopes that he has made some progress on that front.

“I can feel the change. For example, people used to look at me with pity, and now they have a smile on their faces when they meet me and I can only hope they have that same smile when they meet other people with disabilities. If they do, I am the happiest man alive,” he concludes.

This publication has been selected as part of the Srđan Aleksić Youth Competition, a regional storytelling competition that challenges youth to actively engage with their own communities to discover, document, and share stories of moral courage, interethnic cooperation, and positive social change. The competition is a primary component of the Post-Conflict Research Center’s award-winning Ordinary Heroes Peacebuilding Program, which utilizes international stories of rescuer behavior and moral courage to promote interethnic understanding and peace among the citizens of the Western Balkans.

Support for this program has been graciously provided by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).