‘Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Sarajevo, where we lay our scene…’

‘Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Sarajevo, where we lay our scene…’

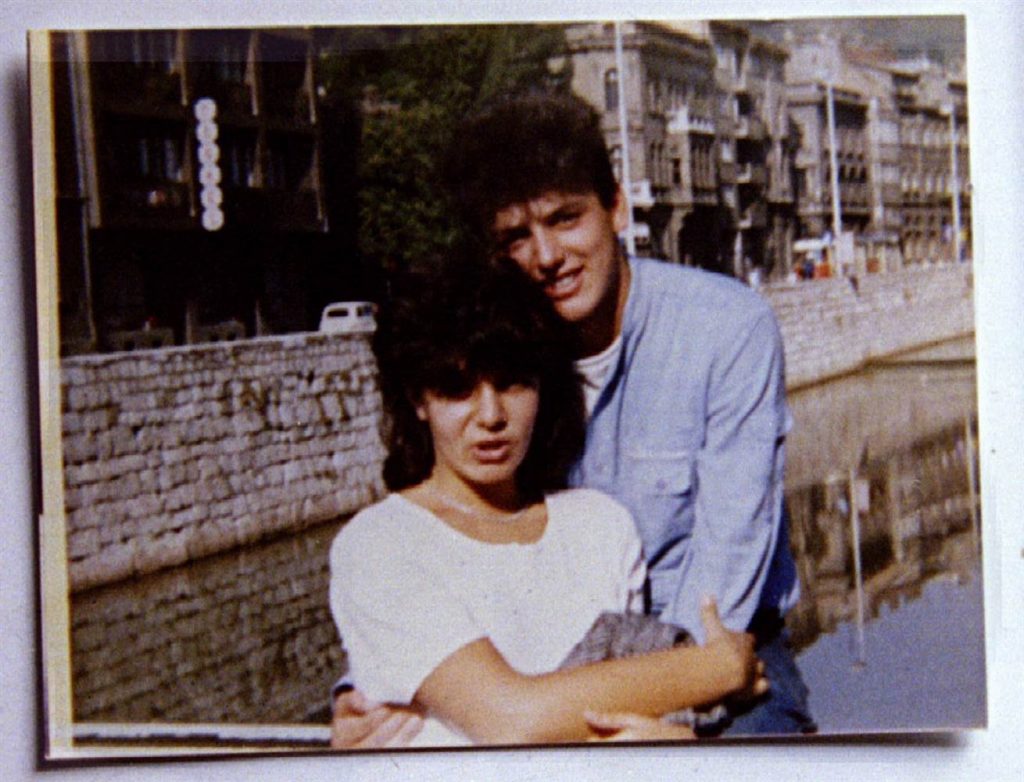

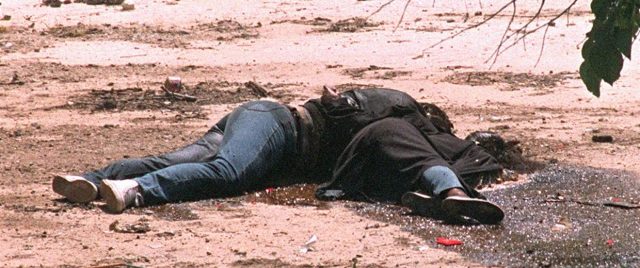

He was a 15-year-old Serb; she, a 16-year-old Muslim. Bosko Brkic and Admira Ismic met at a New Year’s Eve party in Sarajevo. They had been together for nine years when they were killed on 18 May 1993, both aged 25. In their failed attempt to escape the city and country ‘where civil blood was making civil hands unclean’, the couple crossed the Vrbanja bridge – a notoriously advantageous spot for snipers and an area considered ‘no man’s land’. The bridge had already been the site of high profile deaths: two students, Suada Dilibegovic and Olga Sucic, had been killed by a sniper in 1992.[1] A year later, a pacifist was killed at the same spot while placing flowers at the site of their death. In the days following Bosko and Admira’s deaths, Serb rebels and Muslim-led authorities bickered over who lay claim over their bodies, all the while the couple still lay on the bridge, in their last embrace.

The story of Sarajevo’s ‘Romeo & Juliet’ may often be told as a testimony of endurance: love among the ruins, the emotional shield that they carried with them through the ‘hail of bullets and rain of shells’[2] during the five-mile journey between parental homes. Alternatively, the story could be an account of two young people taking a remarkably bold, individual stance against violence. As a report of their deaths noted, ‘in a country mad for war, Bosko and Admira were crazy for each other’[3]; even in the end, they were not swept up in the hate swirling all around them. Any romanticized elevation of this story may seem tasteless given the couple’s tragic and untimely fate, but we can, to an extent, place them on a pedestal for possessing moral courage. When Bosko’s mother Rada once asked Admira: ‘Can this war separate you from Bosko?’ Admira defiantly, yet prophetically, responded: ‘Dear Rada, only bullets can.’[4] But what exactly can be passed on to future generations? That they at least remained true to their feelings for each other, even when the odds were overwhelmingly stacked against them? Maybe, but for all the happiness they gave each other in life, we can’t help but mourn the greater happiness that misfortune denied them. We surely feel the contrast tugging us one way and then the other: both beauty and tragedy lie uncomfortably side-by-side within one story. Though we are reminded of the beauty present in the darkest moments of humanity, it is impossible not to acknowledge the darkness itself. Admira’s father Zijo has a very different take to those who may proclaim the strength of love:

‘[their death is] so hard to believe, such young people disappear in a sudden and violent death – all wishes, all plans are sunk with one bullet…that’s the proof that love cannot conquer all, love cannot win over people who don’t believe in love.’[5]

While we are considering what the long-term legacy of Admira and Bosko will be, the effect of their story to date has been to humanize a conflict widely perceived as intractable. It made the carnage of incessant sniper fire and shelling emotionally tangible. The 1994 PBS documentary ‘Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo’ delivered a story to the world that revealed a parental perspective, which brought the conflict painfully into focus. In the wake of the relentless reports of mass killings and mass rapes, viewers were both overwhelmed and desensitized.[6] ‘Romeo & Juliet’ returns us to such a simple story, we shudder from the shock of its familiarity. These humanizing details make a deep impression on us, especially when we find out how heartbreakingly close they were to making it: they were about two-thirds of the way across the bridge when gunfire opened.[7] Bosko and Admira could be a young couple from anywhere—from Queens, or Tokyo, or Barcelona. We need only change the time and place and the global relevance is apparent; any lessons to be learned are not exclusively for the youth of the Balkans. One example of this international appeal is the use of the documentary’s script by an educational authority in Scotland as a tool to teach children the consequences of ethnic hatred.[8]

Apart from outsourcing the narrative for educational purposes, it has an obvious consequence for the troubled region. That many of the city’s current inhabitants were born after the war[9] provides a reason both for and against looking back into their hateful history. On one hand, there is a need to do so given the youth’s disconnection from history; on the other hand, it is attractive to see the youth as a fresh start, those who can prosper without the regressive anchor of history weighing them down. Furthermore, given the nature of a bitterly protracted siege, the youth of Sarajevo meet the conflict’s legacy quite literally on street corners, outside favorite bars and cafes, and while waiting for the bus. For Rada, she knew that returning to Sarajevo was impossible: ‘I could never walk the streets they once walked.’[10]

Much of what perhaps should be absorbed by the youth is the familial reaction to the couple’s differing backgrounds. Rada had raised Bosko and his brother without any strict framework of religion or nationality; Admira’s parents were just as welcoming to Bosko. Whilst her grandmother was dubious that a mixed relationship could last, the general response of acceptance from both families encapsulates the wider and historical vision of Bosnia and Herzegovina. For much of its history it had been a crossroads of nations, with Sarajevo serving as a cosmopolitan melting pot where Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Catholic, and Orthodox peoples lived together for 500 years[11]. Even as the siege raged on, mixed-marriage ceremonies at City Hall became international media events, an opportunity for the Bosnian government to show the world that the old way of living was still possible.

That, in essence, is why the story of Bosko and Admira is so important: two families scarred by war are joined together by the memory of a couple who dared to love across the ethnic divide[12]. It is this message of hope that could help bring an end to the very concept of loving the ‘wrong’ person. And today? The couple is still lying together, in Sarajevo’s Lion cemetery, continuing to serve as a symbol that defies the ethnically charged hatred[13], a symbol worth the attention of every confused young person in love.

‘A glooming peace this morning with it brings;

The sun, for sorrow, will not show his head:

Go hence, to have more talk of these sad things;

Some shall be pardon’d, and some punished:

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Admira and her Bosko’

—

[1] Andrea Gagliarducci, ‘Romeo and Juliet of Sarajevo’ highlight pain of loss in Bosnian War’ (5/6/15) <http://Bosko.catholicnewsagency.com/news/romeo-and-juliet-of-sarajevo-highlight-pain-of-loss-in-bosnian-war-84494/> [accessed 24/5/17]

[2] John Zaritsky, ‘Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo’ PBS documentary (1994) <https://Bosko.youtube.com/watch?v=jnQ1lTAVjhw> [accessed 23/5/17]

[3] Peter Murtagh, ‘Grim tale of slain Romeo and Juliet’ The Irish Times (25/7/08) <http://Bosko.irishtimes.com/opinion/grim-tale-of-slain-romeo-and-juliet-1.946689> [accessed 23/5/17]

[4] Zaritsky…

[5] Ibid

[6] Bob Herbert, ‘In America; Romeo & Juliet In Bosnia’ (8/5/94) <http://Bosko.nytimes.com/1994/05/08/opinion/in-america-romeo-and-juliet-in-bosnia.html> [accessed 24/5/17]

[7] Herbert…

[8] Murtagh…

[9] Nic Robertson, ‘Tragic ‘Romeo and Juliet’ offers Bosnia hope’ CNN (5/4/12) <http://edition.cnn.com/2012/04/05/world/europe/bosnia-romeo-juliet/> [accessed 22/5/17]

[10] Zaritsky…

[11] Ibid

[12] Robertson…

[13] Ibid