“It was the winter of 1996. The month of March. It was cold, very cold.”

“It was the winter of 1996. The month of March. It was cold, very cold.”

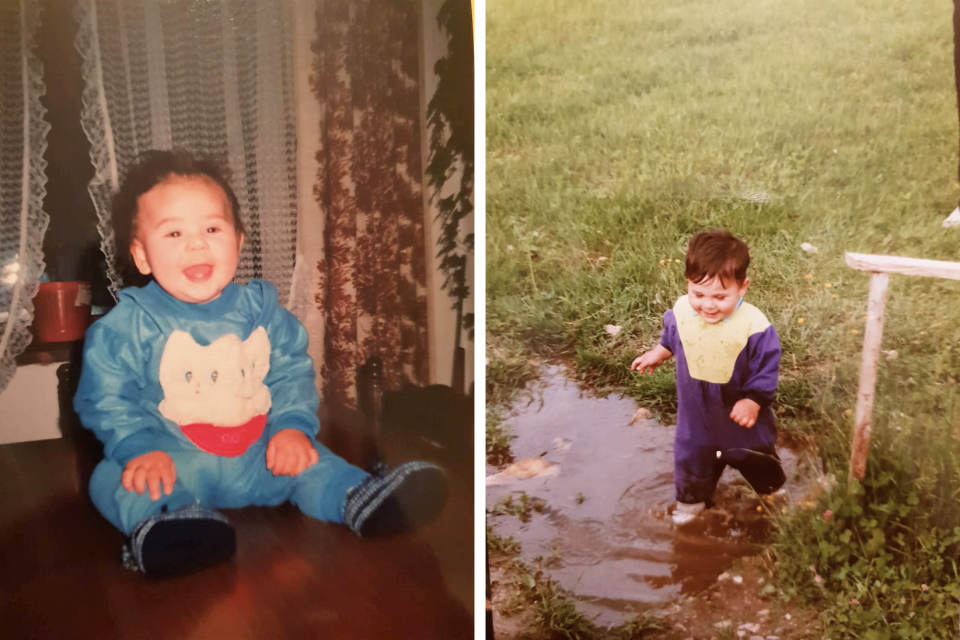

I don’t really remember how it used to be. I’m retelling it how my mom and dad usually talk about it. Back then, we lived in a place near my hometown of Ilijaš. In Podlugovi[1] – the place that artist Zdravko Čolić sings about in his song about the railway station. During our final months there, the population in this small town changed drastically. People changed their places of residence, all of them. We were the rare and unfortunate ones who were still waiting for a truck to load our things in so we could move away.

The anticipation of that truck’s arrival was so great that we weren’t actually living in our house at the time. Instead, we were living in the attic of the neighbor’s house, which everyone knew had already been vacated.

“We lived there? Well, we really not “living”. You and your sisters were just kids back then. It was Dad’s friend, Izet, that placed us there, convincing us that we would be safer, but it was an extremely small space. But we were able to bear it, having in mind that your safety was our greatest concern. Izet did a lot for us back then,” Mom recalls.

Dad had left our house to Izet for safekeeping, but it later turned out that Izet ended up selling all the home’s radiator tubes and roof tiles. In any case, he might be one of my earliest childhood memories. There was this one time when we were absolutely famished, and he brought us a bag full of everything you could imagine. It even contained Eurocream! Mom never mentions this, but I remember it. And I remember him as a man who was dear to my heart.

When asked if they ever left the attic, they said every so often, even if they were afraid.

“Everyone was aware that we didn’t do anything, but you still never knew who had lost someone and how they would perceive things. Once, when I went out into the yard, I remember seeing an old grandma. She was dressed in a long, colorful dimije (traditional baggy trousers) and was twirling her hands while holding a pair of sandals as she walked down the street towards me,” says Mom.

She recalls their conversation.

– Good afternoon!

– Good afternoon gran! How are you?

– I’m fine, thanks for asking! I’m just looking for a house to move into because I had to abandon my own.

– Oh gran, here, move into any of these you like. All of the houses from here to Zenica are empty and free for the choosing!

– Well, my dear. I don’t want to claim just any house; I want one for which I will be given halali (forgiveness) for taking it.

We somehow found the money for the truck and Dad’s brother was put in charge of picking it up and loading all my parents’ personal belongings from the last 34 years onto it. They had so much stuff when they moved for the second time in their mutual lives. Later, we would move five more times.

Dad and Uncle were loading the truck, and, according to Mom, it went awfully slowly. Dad had an excuse for the slow process – after he was injured during the war, a doctor had told him he shouldn’t do any manual labor.

“We were lucky that we covered the trenches with railroad ties. At least we had an abundance of those here. This makeshift cover saved our lives hundreds of times. Once, during the shelling, a grenade hit the trench we were in, landing on the railroad ties directly above us. We survived that grenade explosion thanks to those ties, but we were jolted by the detonation. It was after that incident that the doctor told me I shouldn’t lift anything heavier than a spoon,” Dad remembers.

Unfortunately, the soldiers would soon arrive to our town. I say (un)fortunately because they were likely the enemy soldiers, so that’s why we had to move. With minimal conversation, we began loading our stuff onto the trailer of the green truck.

– Where will I put this?

– On the left, right next to the armoire.

– Here?

– Meh, you can also put it there, f*ck it!

Thus, as the free space in the truck disappeared, so did our hopes that everything would end. A few moments later:

– No more. It’s full.

– Full to the brim.

– Can you, at least, put this tepsija (baking dish) in?

– Let’s try.

– Nope, not a chance.

“It was a fine tepsija. I often made bread and pie in it,” Mom says about the tepsija she left behind. As I gazed at her, she excitedly and proudly continued: “And then I took that tepsija and tossed it as far as I could over the fence. Oh, how many times I had used it.”

As the conversation continues at the dining room table, Mom is putting dough in a blue tepsija. The dish was a bit sooty at the bottom which reminded her of the one she abandoned.

– It was similar to this one.

– It was similar?

– This one’s not exactly the same. The other one was bigger.

– Well, Mom, it’s pretty much the same size as the dish you left behind.

– You don’t know anything.

What I also didn’t know was whether that sad grandma ever found halali (forgiveness) for taking a house. And I still find it hard to believe that railroad ties could really protect you from grenade blasts. I don’t know how many will either judge Izet or understand him like my dad does, as he believes that everyone, deep down, is good by nature. What I know for certain is that Mom has at least 10 new tepsijas. However, every time I come home on Saturdays and we bake pies, she tells the same story about the tepsija that she’s never gotten over and is still mourning the loss of to this day.

Now, the forlorn migrants that are passing through Bosnia and Herzegovina, who are fleeing war and looking for a better life, are collectively referred to as “a migrant crisis and a danger to society”.

When I think about it, I wonder how many of their own blue, sooty tepsijas they’ve had to abandon when they were forced to flee their homes. How many of their fathers’ lives were not spared by the rudimentary protection of railroad ties? How many enemy soldiers have forced them to emigrate? We were never animals until the very end. We do not need to be animals now either. In our country, time has done its thing, but we are always reminded of that unlucky war through the stories of our parents. Time has done its thing. What are we doing?

[1] Ilijaš is a settlement and a municipality located in Sarajevo Canton, northwest of the city of Sarajevo. It consists of several settlements. One of those settlements is Podlugovi.

This publication has been selected as part of the Srđan Aleksić Youth Competition, a regional storytelling competition that challenges youth to actively engage with their own communities to discover, document, and share stories of moral courage, interethnic cooperation, and positive social change. The competition is a primary component of the Post-Conflict Research Center’s award-winning Ordinary Heroes Peacebuilding Program, which utilizes international stories of rescuer behavior and moral courage to promote interethnic understanding and peace among the citizens of the Western Balkans.

The Balkan Diskurs Youth Correspondent Program is made possible by funding from the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).