This prevalence of Islamophobia in Bosnia and in EU refugee policy prompts questions about change and reform, especially given the imminent need to respond to modern conflicts affecting Muslims.

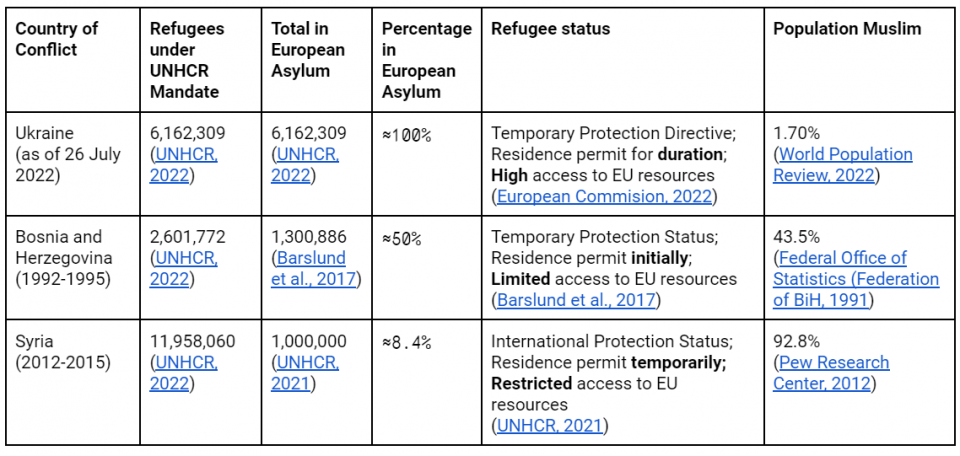

The 2022 Ukrainian War and refugee surge prompted EU policy that welcomes Ukrainians but contradicts EU responses to Bosnian and Syrian refugees in 1992 and 2012. This double-standard towards non-Muslims and Muslims suggests a continuity in Islamophobic sentiments over the last 30 years.

Since the start of the Russian invasion in February 2022, Ukrainians have been subjected to violence and war crimes on a massive scale, with the New Lines Institute even concluding that “there exists a serious risk of genocide” within Ukraine (Diamond, 2022). This horrific violence and destruction has led to the displacement of nearly 15 million Ukrainians (8 million internally and about 7 million refugees), making this the worst year on record of forcible displacement (Karasapan, 2022).

In response to this tragedy and the resultant surge of Ukrainian refugees, European countries opened their borders and implemented policies to grant Ukrainian refugees asylum – notably, the Temporary Protection Directive.

While created in 2001 following the conflicts in former Yugoslavia, the Temporary Protection Directive was activated for the first time this year in response to the Ukrainian War. The Temporary Protection Directive grants refugees many of the same living and working rights as EU citizens, including a residence permit for the entire duration of their protection and access to employment, accommodation, social welfare, medical care, education, and free movement through the EU (European Commision, 2022).

With the start of the Bosnian War 30 years prior, approximately 1.3 million Bosnian refugees fled to Western Europe, escaping destruction, sexual violence, and genocide, much as Ukrainians are doing today (Barslund et al., 2017). However, Western European countries only granted Bosnian refugees initial temporary residency, limited access to labor and education, limited integration measures, and limited financial support (Barslund et al., 2017). In the Dayton Agreement which ended the Bosnian War, European countries prioritized measures to return refugees to Bosnia and Herzegovina despite persisting ethnic tensions and economic difficulties in the country (Barslund et al., 2017).

While the conflicts in both Ukraine and Bosnia featured extreme levels of violence and created influxes of refugees, these countries received unequal responses from European refugee policy. In considering the reason for this disparate treatment, one cannot help but notice the differing religious demographics – while Ukraine is a majority Christian state, Bosnia is predominately Muslim.

Professor Mehnaz Afridi, the Director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Interfaith Education Center at Manhattan College, views “temporary protection for the Ukrainians as a double standard.” She acknowledges a geopolitical motivation for Europe, suggesting “the reason the international community has done so much for Ukraine is that their real nervousness is about Russia and Russia’s power in that region, because Russia could spread back into Ukraine, usurping Ukraine and potentially other parts of Eastern Europe.”

However, in addition to this geopolitical factor, Afridi attributes the double standard to Islamophobic sentiments within Western Europe. “There is this fear of people letting in Muslims because they are perceived as connected to extremism, violence,” she said. “When Muslims suffer,” Afridi observes, “there’s less of an open door.”

Closed Doors

Since the Bosnian War, other Muslim groups have similarly experienced Europe’s “closed door.” With the escalation of the Syrian War in 2012, there were nearly 12 million refugees under the UNHCR Mandate (UNHCR, 2012). While Europe accepted one million Syrian refugees, the majority have only been afforded an international protection status—the Temporary Protection Directive was not activated (UNHCR, 2021).

Contrary to the provisions of the Temporary Protection Directive, an international protection status only provides limited access to residence permits, travel documents, employment, education, social welfare, healthcare, and accommodation (European Commission, 2022). These rights are further compromised as European countries increase the pressure on refugees to return to Syria, despite the dangers of the ongoing war and unsafe conditions for return. Even though these problems in Syria persist, European efforts to classify Syria as a safe country are on the rise, with countries such as Denmark even revoking some refugees’ residency permits (Sly, 2021).

Islamophobia in Bosnia and Herzegovina

While the West certainly treated Bosnian refugees differently from how they are treating Ukrainian refugees today, Bosnian Muslims experience Islamophobia distinctly from their Arab Muslim counterparts.

Islamophobia is rooted in misperceptions of Muslims, including flawed stereotypes and misguided associations with extremism and violence. While “people see Muslims as Oriental, Asiatic-African, mostly Arab,” Middle Eastern Arabs actually make up “only 20% of the global Muslim population,” Afridi revealed. “People don’t know that Muslims are Europeans,” she explains. “There’s stereotyping of what Muslims are, where they live, how they live, and that has been inflated since 9/11.”

Because of these false perceptions, Arab Muslims, including Syrians, are assumed to be violent and dangerous. “There’s very little done to help them and let them in the country because of the fear of who they are.” Facing this religious discrimination and Islamophobia, Arab Muslims receive different and unequal aid compared to non-Muslims.

“Islamophobia in Bosnia is not the same as Islamophobia in Europe,” explained Hikmet Karčić, a Sarajevo-based genocide scholar and author of Torture, Humiliate, Kill: Inside the Bosnian Serb Camp System, “because Bosniaks here are local Europeans.” Like other Europeans, Bosnian Muslims are fair-skinned and dress in Western fashions. Since they do not fit into the Muslim stereotype, Bosniaks are do not face the same discrimination and presumptions as Arab Muslims who are conceptualized as an essentially foreign and extremist threat to the West. Nevertheless, Bosnian Muslims still encounter Islamophobia, evident through genocide denial starting during the Bosnian War and persisting still today.

During the Bosnian War, “Islamophobia or anti-Muslim bigotry was one of the reasons Muslims were targeted in the first place,” said Karčić, noting that these anti-Muslim sentiments continue still 30 years later after the end of the war. “To some extent, Islamophobia has a lot to do with genocide denial itself to this day.”

Calling the genocide ‘ethnic cleansing’ allowed Western countries to ignore the fact that these crimes were specifically committed against Muslims. “It wasn’t ‘ethnic cleansing,’” Afridi emphasized. “It was really about killing Bosniaks.”

Additionally, with the terminology of ‘ethnic cleansing’ Western countries justified their noninvolvement in the war. “If you use the term ‘genocide,’ you’re obliged to intervene according to the UN Convention,” said Karčić, “but if you use a new term such as ‘ethnic cleansing,’ then you don’t have to intervene because it’s not genocide.”

Today, according to the 2020 European Islamophobia Report, Bosnians still experience Islamophobia, generated predominantly by Bosnian Serb politicians, media, and academia. This Islamophobia is evident in education, where war criminals are celebrated in public schools and Bosniaks are denied the opportunity to study the Bosnian language in Republika Srpska. In politics, Bosnian Serb authorities use Islamophobic rhetoric, especially to mobilize voters during election season, creating videos with derogatory portrayals of Bosniaks. Bosnian Serb leaders such as Milorad Dodik, for instance, frequently make baseless claims about the threat of “Islamic terrorism” in the country. In the media, Islamophobia also often manifests in the form of fake news falsely associating Bosniaks with terrorism (European Islamophobia Report, 2021).

Shaping the Future

The disparity between Europe’s policy response to Ukrainian refugees and its response to Bosnian and Syrian refugees reveals an Islamophobic attitude that has remained consistent for over 30 years.

Given the prevalence of anti-Muslim violence in many parts of the world, such as against the Uighurs in China and the Rohingya in Myanmar, Afridi stresses the importance of taking action to curb future conflict and ensure Muslims receive aid. “If we stand idly by when there’s genocide against Muslims, we have to know that there is a future and a cycle of memory.”

To combat Islamophobia, Afridi suggests that non-Muslims and Muslims engage in dialogue to gain a greater understanding of one another and debunk Islamophobic stereotypes and perceptions. “Religion is also about cultural understanding, cultural sensitivity, diversity, and interfaith alliances,” she said. Through building an understanding of other religions, people can also develop empathy and perspective to work together and live peacefully with members of other groups.

In light of its global political and economic power, the EU is uniquely positioned both to accommodate displaced people and to combat Islamophobia. In an official statement, the EU stated its intent to “guarantee high standards of protection for refugees,” indicating a desire to help those facing violence from around the world (EU, 2022). Since the adoption of the 1951 Refugee Convention, the first European act to provide asylum to international refugees, European countries have undertaken reforms and created new policies to strengthen their refugee policy. This includes the 2001 Temporary Protection Direction following the Bosnian conflict, as well as 2016-2017 legislation and the establishment of the European Union Asylum Agency which was intended to increase equality and fairness in refugee policy in response to the influx of Syrian refugees during that period (EU, 2022).

Despite these reforms and successes, there is a great deal of potential within the EU to further improve its refugee policy and ensure the same status and rights to all refugees regardless of religion. By recognizing and fighting Islamophobia, Europe can help break the cycle of religious inequality and set the world on the right track to combatting violence against Muslims and promoting interfaith peace.