In Busovača Municipality, located in the Central Bosnia Canton, two high schools share one building but operate on different curricula.

The students in both schools are the same age and use the same classrooms, but at different times. Students who attend class in the mornings study according to Croatian curriculum, while those who attend in the afternoons follow Bosnian curriculum. Half an hour of silence in the classrooms and corridors separates the students in the first and second shifts. This shows a division that students find very strange. They imagine all the things they could do together — from school projects and activities to socializing and attending classes side by side.

The practice known as “two schools under one roof” was established after the war as a temporary measure in three cantons in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Central Bosnia, Zenica-Doboj, and Herzegovina-Neretva. Here, children of different ethnicities attend classes according to different curricula and programs. The rationale behind this system was to ensure that at least one school in every locality was equipped with adequate classrooms and that these classrooms were accessible to all students. However, 30 years after the war, this temporary measure remains in place without a systemic solution for the transition to integrated schools.

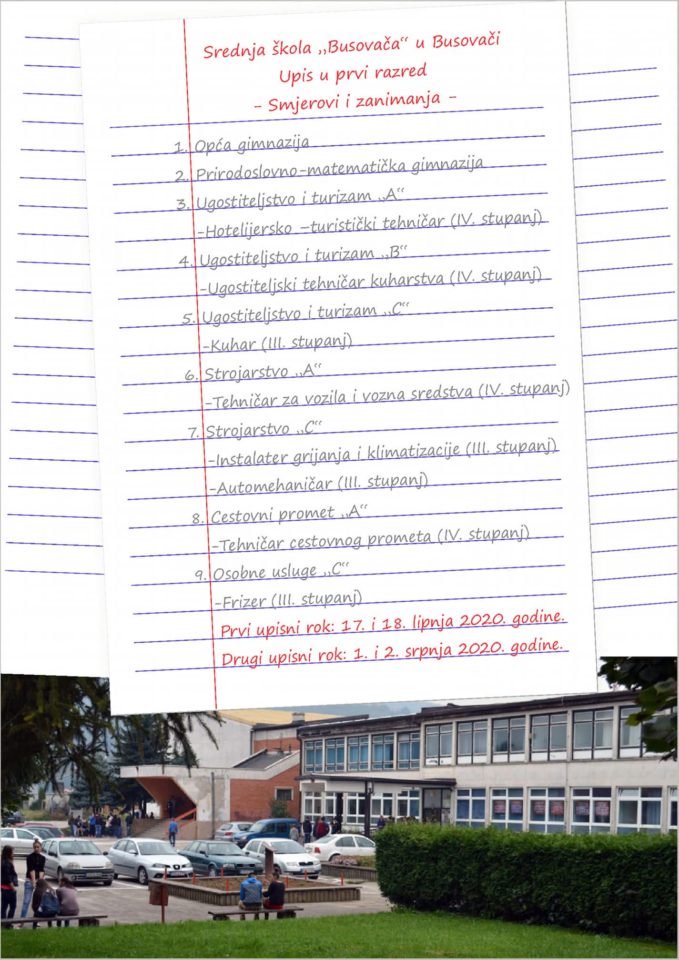

This is the case in Busovača. A single building houses the Busovača High School, which follows Croatian curriculum and operates between 7 a.m. and 1 p.m., and the Mixed High School, which teaches Bosnian curriculum and operates from 1:30 p.m. until 7 or 10 p.m.

“Almost No Chance to Meet”

Patrik Krišto is a second-year high school student who attends the first shift and studies in the road traffic technician program. Reflecting on his experience of the “two schools under one roof” system, he stated: “At first it was strange, because you know you go to the same school as someone, but you never see them.” He adds that he has gotten used to it over time, but the feeling of separation among his peers remains.

“I feel like it’s two schools, not one. We come, we do our thing, and then they do their thing. We hardly have a chance to get to know each other,” said Petar Vrhovac, a third-year high school student who studies forestry during the morning shift.

Sajra Srebrenica, a second-year student of mechanical engineering, attends the afternoon classes at the high school in Busovača. She says that the division between the first and second shifts is more limiting than one might think, and she often thinks about the missed opportunities to do things together, from school projects and activities to hanging out.

Elmin Tabaković is a third-year mechanical engineering student who also attends the second shift. He believes that “it isn’t natural to share a school and yet be separated.”

“We have so many common interests, but the system separates us like we’re different – and we’re not.”

According to Patrik, joint classes with peers from both shifts would be useful and allow students to better get to know one another. “There are fewer prejudices when you know someone personally and not just from stories,” he said.

His peer from the second shift, Sajra, agrees that joint classes would teach them tolerance and cooperation, which they don’t learn from textbooks.

Diversity is a Strength, Not an Obstacle

“I imagine a school where differences are respected but not emphasized as an obstacle. One school – one collective,” says Petar from the first shift.

Elmin from the second shift envisions the opportunity to learn and socialize together with first-shift students without segregation as the way forward. Friendships shouldn’t depend on what shift students attend, but on common interests and personalities. “I think that would be easier, more pleasant, and happier for everyone,” he added.

From conversations with students from the Busovača Mixed High School and Busovača High School, it becomes clear that they don’t want the school bell to separate them, but rather to bring them together. Despite being separated by this system—and very often by the attitudes of older generations—Patrik, Petar, Elmin, and Sajra want to go to a school where they can share knowledge, socialize, and respect each other, regardless of curriculum. While the first shift is learning Croatian geography and history and the second is learning Bosnian, these young people say that it is time for change. This change begins with a simple question: Why shouldn’t we be together?

While young people want change, it is still difficult to predict whether this change will actually come to pass, given the divided and inconsistent views of government representatives who are supposed to initiate educational reform.