In the thirty years since the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, film has become an integral part of the remembrance process.

In the wake of war, film can both offer a window into trauma and bring to light suppressed or fragmented collective memories. Additionally, films have a unique capacity to disrupt dominant narratives, thus bridging communal divides.

According to Sarina Bakić, associate professor of Political Sciences at the University of Sarajevo, within Bosnian society, “film functions as a cultural and political tool that helps shape how communities remember and interpret past violence, trauma, and identity.”

As she explains, “while monuments often freeze memory into a single symbol, cinema offers nuanced, unfolding narratives that reflect moral ambiguity and emotional contradictions of real human experiences. Film resists the hero/victim binary often present in official commemorations, encouraging critical reflection instead of ritual affirmation.” This ultimately fosters a “relational understanding of suffering”, allowing viewers to process collective trauma in ways that static memorials, courtroom testimony, or historical records rarely permit

The Growing Social Significance of Bosnian war films and cinema

According to Etami Borjan, from the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb, since the 1990s coming to terms with the past has been a central topic in public discourses, and the excessive presence of war in post-Yugoslav cinema could be seen as necessary exercise of coming to terms with the wartime traumas.

Bakić emphasizes that “Bosnian cinema has notably foregrounded women’s experiences of war, rape, widowhood, and post-war silence, which are often ignored in official memory politics.”

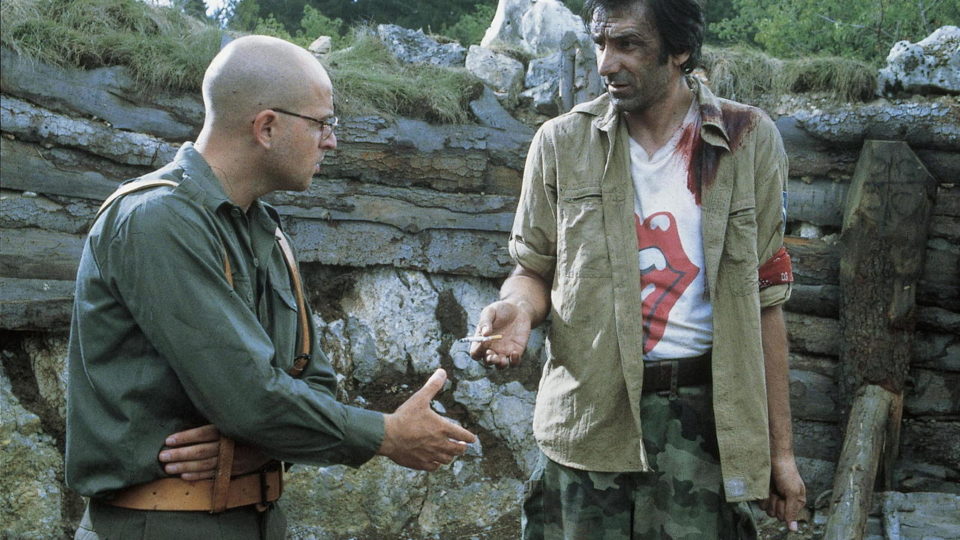

One of the earliest and most internationally recognized Bosnian war films is No Man’s Land (2001), directed by Danis Tanović. Set in 1993, the plot follows the experience of a wounded Bosniak and a Bosnian Serb soldier trapped between the front lines. It places the men in a literal and symbolic middle ground, hence emphasizing their shared humanity over any ethnic division. Dino Murtić in his book Post-Yugoslav Cinema: Towards a Cosmopolitan Imagining, describes films such as No Man’s Land as “crucial to articulating our understanding of what it means to be human against the backdrop of political disintegration.”

One of the most influential forces supporting Bosnia’s postwar cinematic development has been the Sarajevo Film Festival. Founded by the Obala Art Centar in 1995 during the Sarajevo siege, the festival was envisioned as a form of cultural resistance.

Maša Marković, the head of the SFF Industry Department, attests to the festival’s triumph over adversity during the siege: “The Sarajevo Film Festival was born from the siege of Sarajevo as a symbol of cultural resistance.” She adds that the goal of the festival has always been to showcase the most significant achievements in world cinema to local audiences, fostering a safe environment for filmmakers and spectators.

According to research by Véronique Labonte from the Université Laval Canada, despite possessing one of the highest numbers of media outlets per capita in the world, the media industry suffers from a lack of transparency and non-partisanship, pushing consumers away from such traditional platforms of communication, especially amongst younger generations. Thus, the type of work offered by SFF plays an important role in Bosnia’s postwar peacebuilding process where the media is widely distrusted.

This is the Past, but What is the Future?

The emotional resonance of film is precisely what makes this form of storytelling essential in the aftermath of violence. Chris Leslie, a Scottish filmmaker who has extensively documented Bosnian society, warns that the overwhelming nature of a conflict like Bosnia’s risks driving people to “switch off,” eliminating possibilities for reconciliation. However, cinema has the power to pull them back in. “The emotion of a film and a story is something that we can all relate to,” Leslie explains. Stories resonate with people when they see their experiences reflected on the screen. Accordingly, local filmmaking becomes more than a form of cultural resistance: it becomes a vehicle for healing.

One such example is Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida? (2020), nominated for an Oscar in 2021. The film moves fluidly across time, utilizing metaphors of memory and forgetting to bridge the events of the Srebrenica genocide and the present. At its core, the film is centered around unimaginable loss. Yet in the final scene, when Aida returns to Srebrenica to continue teaching, it suggests the possibility of coexistence. According to researchers, it is through these final scenes that Quo Vadis, Aida? exemplifies how cinema can confront the past while simultaneously displaying present realities in a new light.

Although cinema’s capacity to impact memory is undeniable, one would be remiss to overlook the risk of such influence. Leslie cautions that “at the end of the day, a film is a story. And it is a crafted story. That they are to be used as an educational tool can be worrying.”

Bakić also observes that “state and political elites may sponsor films as part of nation-building projects, using them to promote unity, glorify resistance or justify political ideologies.” It is an influence which will taint any story and, in fragmented societies, can deepen social cohesion if the past is not represented inclusively.

“Maybe the idea is that this is the past, but what is the future?” ponders Leslie. As Bosnia and Herzegovina continues to grapple with its past, the challenge for the film industry might become less about remembering the past and more about imagining what lies ahead.