“If I can use my trauma to help other people process theirs, no matter where they come from or what their background is, then that’s my obligation and my service in this world.”

These are the words of Sabina Vajrača, a Banja Luka native. She left Bosnia and Herzegovina due to the war and made her way to the United States. A filmmaker, rescuer, and philosopher, she uses her work, including the film “Back to Bosnia,” to confront the past, empower others, and create art they can connect with.

Her passion for the arts began in early childhood, when, around the age of eight, she realized she wanted to become a film director. Her father, a self-proclaimed cinephile, first introduced her to the world of film. Growing up in Banja Luka, she remembers when the city was not divided by religion or ethnicity. However, life quickly changed for her and her family when she was forced to flee Banja Luka in 1992, just a few months into the war.

Sabina reflects on that period, saying that her family had remained in Banja Luka, leaving her faced with feelings of loneliness and a sense of losing the support and love she once had. “I needed at the time to be loved and taken care of by my family. I wasn’t ready to be on my own,” she says.

Nevertheless, she credits her path as having saved her during this period of her life, when she stumbled upon a theatre company in Zagreb. She explained that the theatre and arts were the one thing “keeping her afloat.” As many of her peers struggled with depression and turned to substance abuse to cope with the highly traumatic events, theatre was a beacon of hope during this dark period of her life.

Eventually, Sabina, joined by her mother and brother in the United States and they didn’t even know whether or not Sabina’s father was alive. And yet, through it all, she remained committed to starting a career in the arts. Asked whether she felt pressure from her family to pursue something more practical, Sabina credits her mother for having given her the freedom to choose her own path and happiness.

“My dad helped and saved a lot of people [during the war], and my dad is an incredible human being. A lot of people rightfully call him a hero, but in my personal story, my mother is the biggest hero,” she says.

Storytelling became an escape for Sabina. The ability to write and tell stories provided her with an outlet where she became increasingly comfortable in her new life, yet at the same time, she felt she had to grow up twice as fast. She remembers feeling as though her generation was losing their adolescence as they navigated growing up amid the uncertainty of war. There was no time to experiment with who she was because she needed to focus on taking care of herself and her brother.

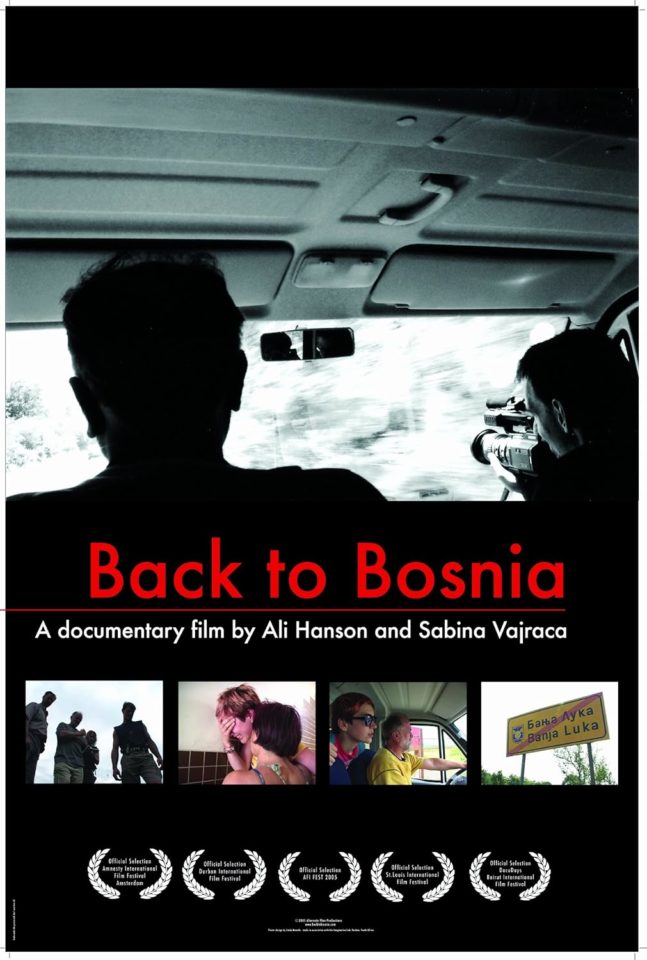

Sabina studied theatre in Florida before moving to New York City to pursue a career as a director. It was while she was in New York that she decided to create the documentary Back to Bosnia, after her family was notified that they could return to Banja Luka to reclaim their home. For the first time, Sabina would be flipping the camera on herself and her family, forcing her to confront the uncomfortable emotions she had pushed aside all these years.

The making of Back to Bosnia was Sabina’s second time returning to Banja Luka since the end of the war. Her first trip back was six months prior to filming and was a pivotal moment in her mental health journey. She recalls being unprepared for how she would react upon returning after all those years. She mourned the Banja Luka she once knew, saying, “The biggest heartbreak is the loss of the world that we loved and believed in.”

Upon returning to New York City, she fell into a pit of depression. When she confided in a childhood friend about her experiences, he told her this was normal for many young people when returning to Bosnia for the first time. This pivotal moment inspired her to create a film where people like her could relate and feel seen, leading her to accompany her father so he would not be alone on his first return home.

During the filming of Back to Bosnia, Sabina was thrown into what she could only describe as 24/7 therapy for three years. She went into the experience unprepared for the emotions this project would evoke. Like many others from her generation, she wanted to avoid the healing process altogether, feeling it would be too daunting. The emotional toll of the film led her to take a break from working on any projects related to Bosnia.

During this time, Sabina became involved with a philosophy school in New York City that encouraged her to sift through much of the trauma she had been living with for all these years. Through this process, she realized how many people in her community were not doing the same work she was doing, including her family. “My parents put a Band-Aid on a broken leg, hoping it would heal itself,” she says. While unpacking her intergenerational trauma, she felt called to help others tap into their inner healing and process the trauma they had lived through so as not to pass it on to the next generation. This journey led her to start creating projects about Bosnia again and explore similar themes of trauma to help her community.

When asked what she would like Bosnian youth to take away from her work, Sabina says, “Perhaps they can use it to help understand where their ancestors come from and what they are really heartbroken about.” She remembers a time before the war, when, in her experience, there was little division, saying, “We’re nostalgic for a Bosnia they will never know.”

Sabina believes her films can help young people to better understand where their pain and their inherited trauma come from. She hopes that they will come to love Bosnia as much as those who remember it before the war.