Bosnia and Herzegovina is currently home to some 1,000 illegal landfills, representing not only an ecological problem but a hazard to the safety, health, and wellbeing of citizens throughout the country.

From Zenica to Mostar, Tuzla to Višegrad, illegal dumping sites have been left relatively unaddressed by municipalities as well as larger entities controlling environmental activities within Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH).

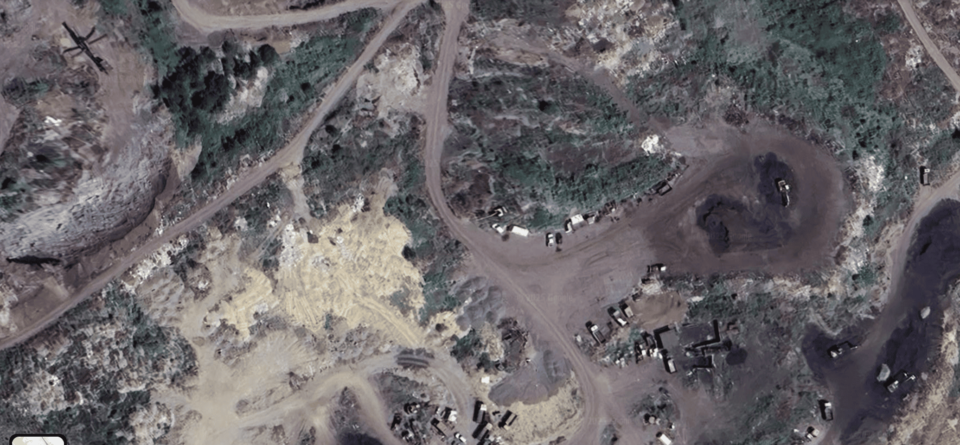

Extensive reports on the issue of landfills have determined that around 25% of all disposed waste in BiH ends up in illegal dump sites, and that most legal landfills do not meet European Union (EU) or even domestic environmental standards. Unsanctioned waste sites spring up all over the country, some used by individuals, some by industrial companies, and some even by municipalities, making them extremely difficult to govern.

The presence of such illegal landfills, or even legal ones that are not functioning sustainably, has obvious implications for the immediate environment and biodiversity in the area. According to the Circular Economy Transition Action Plan (CETAP), BiH currently contains over 5,000 species of vascular plants and countless species of animals. Landfills threaten the health and the existence of this biodiversity, putting ecosystems at risk and ruining conservation efforts. Rivers throughout BiH are filling up with waste, contaminating water supplies. Additionally, organic waste emits methane, a greenhouse gas with 80 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide, and the waste at these sites is occasionally burned, emitting various toxins into the air and water.

Protecting biodiversity and maintaining healthy ecosystems is, of course, vital, but these landfills also pose a threat to human health and safety. Beyond the environmental challenge, these sites also have serious social and political implications. Mario Crnković, an environmental activist from the grassroots organization Green Team in northwestern BiH, explains the risks:

“Wild and illegal dumpsites can contaminate drinking water, air, and soil, increasing the risk of heavy metal poisoning. They contribute to the development of cancer and facilitate the spread of disease through rodents and insects. Open burning of waste releases hazardous particles and carcinogenic compounds, while microplastics and chemicals enter the food chain.”

Improperly regulated waste mismanagement continues to pose a multitude of threats to human health and ecosystems, but Crnković believes that these problems are not unsolvable.

Demands from environmental organizations and activists around the country have increased discussions of the issue, in the hope of raising awareness and encouraging accountability from companies, municipalities, federal institutions, and international actors. In September of this year, the citizens’ association “Jer nas se tiče” demanded an inspection of the Uborak landfill in Mostar, resulting in the halting of municipal waste disposal at the site until an environmental permit is acquired. The director of Deponija, the company that manages the Uborak landfill, claims that they “regularly monitor water, air, and soil quality, and that no test results have ever shown exceedances,” despite findings by the Center for Investigative Reporting that the landfill had long been operating without a permit.

Even with increasing documentation and awareness of the issues of illegal landfills in BiH, generating civic engagement on environmental issues is no easy task. Samir Lemeš, an environmental activist with Eko Forum Zenica and professor at the University of Zenica, explains that “it’s very difficult to educate the population, as there’s a widespread opinion that ‘if we have to take care of the environment, we will then lose the employment,’” and that “even the decision makers often neglect the real cost of environmental hazards.”

A landfill as an example for others

Regarding the situation in Zenica, Lemeš describes the two main landfills in the city: “Mošćanica is the communal waste depot with fairly good governance, created with help from international donors and loans and managed by the city. There are constant improvements and systemic investments to maintain this landfill as an example for other Bosnian municipalities. Rača, on the other hand, is an illegal industrial waste depot where millions of tons of industrial waste from the steelworks mix with ashes, sludge, and other types of waste.”

The contrast between these two sites represents the successes and failures of waste management policy in BiH. While there is potential to create more sustainable and compliant landfills, the illegal ones continue to run rampant, without plans to regulate them or shut them down and without accountability or penalties for their continued operation.

Northwestern BiH faces similar environmental problems, as Crnković explains, including “continuous strain on rivers through illegal construction and uncontrolled wastewater discharge, land degradation caused by illegal and unsanitary dumpsites.” On top of local waste mismanagement, which Crnković describes as “the consequence of a failed system,” threats of outside radioactive waste from the Croatian border are a cause of concern for those living in cities like Novi Grad.

“If one country, particularly a member of the European Union, is able to place radioactive waste from a nuclear power plant and other hazardous waste on its border with a neighboring state without the consent of the affected population and without conducting all relevant studies, a precedent will be set that could be replicated anywhere,” notes Crnković. While not directly tied to the presence of illegal dumpsites in the region, establishing BiH as a dumping ground for hazardous waste only opens the door wider for waste mismanagement by both internal and external actors.

“The question of illegal landfills is related both to poor economic conditions and poor legislation enforcement,” Professor Lemeš states. There are existing laws and treatises such as the Law on Waste Management and the Sofia Declaration on the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, which align with European standards and have the potential to reduce environmental risks in the country. In practice, however, these are under-implemented and thus somewhat ineffective. Compounding insufficient inspection capacities, “low penalties are not powerful enough to deter companies from illegal industrial waste disposal,” Professor Lemeš explains. Rather than comply with municipal and cantonal standards, companies and even individuals often opt to pay small fines and continue with the same waste management practices.

Stricter penalties for those who violate the law

Both Lemeš and Crnković agree that penalties for those violating waste management laws should be stricter in order to serve as a deterrent for those harming the environment. Furthermore, while many citizens worry about the expense of better waste sorting and collection services, local authorities could implement “modest increases…combined with subsidies for municipal utility companies at the local and higher government levels” to improve services and prevent development of uncontrolled landfills, Crnković suggests.

With EU accession constantly dominating public discourse in BiH, environmental issues have not only social and ecological implications, but also political ones. To confront global challenges such as climate change, everyone must do their part to protect the environment and mitigate harm, but these issues are also important for the political future of BiH. As a condition for membership, BiH must implement the EU’s environmental acquis, including laws on air, water, soil, waste management, and emissions. Compliance with these standards is thus crucial if the country has aims for a European future, but without investment in long-term solutions and the will of civil society to demand change, this becomes an increasingly difficult goal.

Crnković concluded by sharing the motivation behind his environmental activism and his hopes for the future of BiH: “At the root of the problem is the fact that environmental protection is often seen as a cost, without understanding that it’s an investment in health, safety, and the economy, both for those of us living here today and for future generations… At times, it can be challenging, but fighting for your home, for the river you grew up along, and for the opportunity for those you love to live in a healthy environment is a meaningful calling.”