Tito’s bunker is one of the largest and best-kept State secrets of the former Yugoslavia. Clara Casagrande and Marion Pineau explore.

Located 50km southwest of Sarajevo in the town of Konjic, Tito’s bunker is one of the largest and best-kept State secrets of the former Yugoslavia. The construction, started in March 1953 upon Tito’s order, was done in total secrecy; not even the nearest neighbors knew about it. The teams of workers were replaced regularly so that no one would know too much about the bunker, and the workers were even transported there blindfolded so they wouldn’t know its exact location. Even upon the bunker’s completion 26 years later in September of 1979, few people knew about its existence, and only four generals were allowed to enter it.

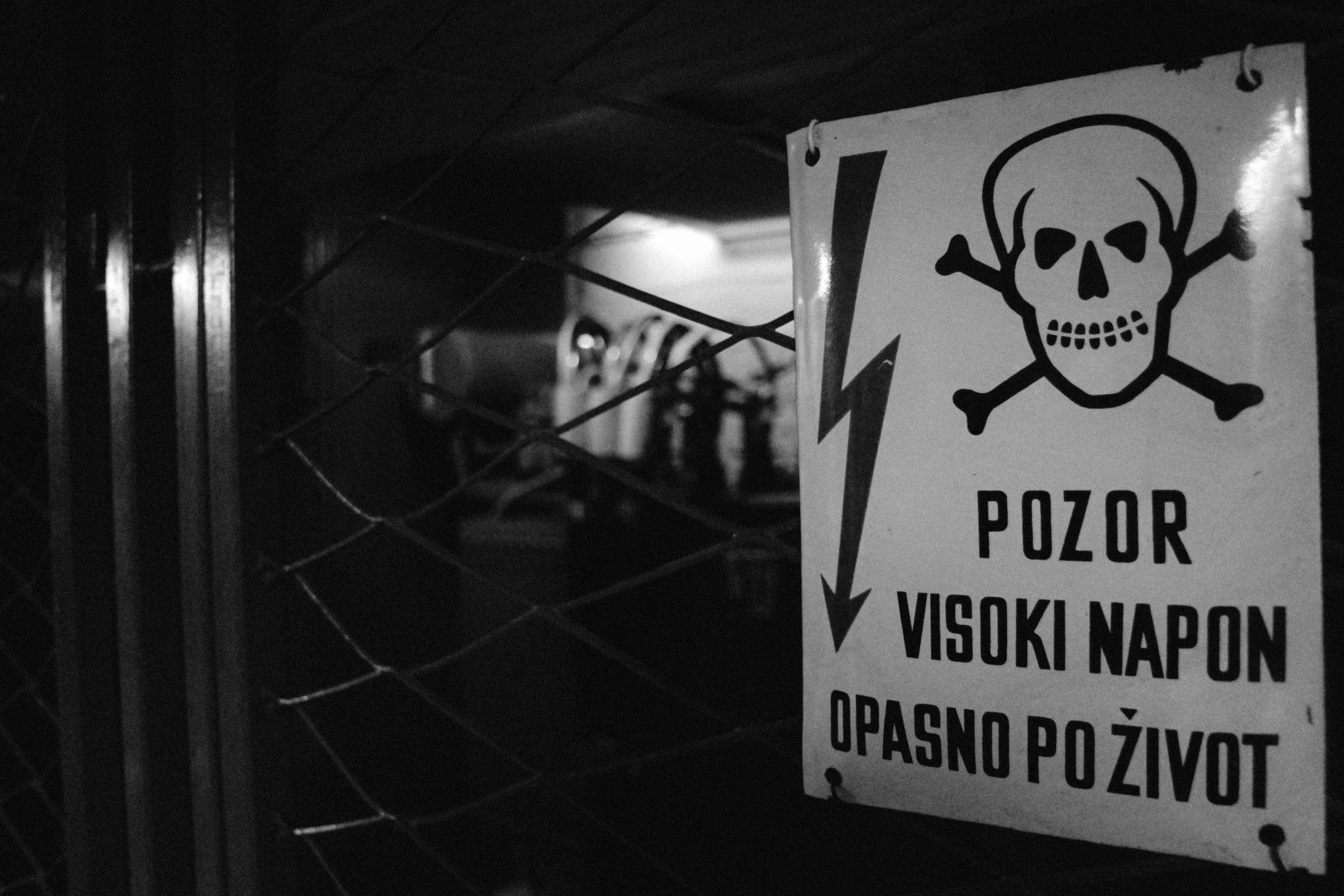

Designed to shelter the country’s ruling elites in the case of a nuclear attack, the bunker, with a total area of 6,854 m2, could resist a bomb attack of up to 25 kilotons, which is far more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima. It could then accommodate President Tito, his family and his closest associates (approximately 350 people), so that they could continue to govern the country—or what was left of it. They could live and work self-sufficiently for six months without ever coming up for air and without any contact with the outside world. Residents were provided with everything from food and drinking water to air conditioning and cable television in every room.

The bunker cost around 5 billion dollars, making it the third most expensive project of the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. Today, it is still not easy to access. The entrance looks like an ordinary house, at the end of a lonely road just east of Konjic.

The shelter is built in the shape of a horseshoe. On the top of the “horseshoe” are the entrances, and inside the horseshoe—in the most heavily protected sector—are the blocks designated for use by the president and the government. The innermost point is located 202 meters from the entrance and 280 meters from the top of the mountain.

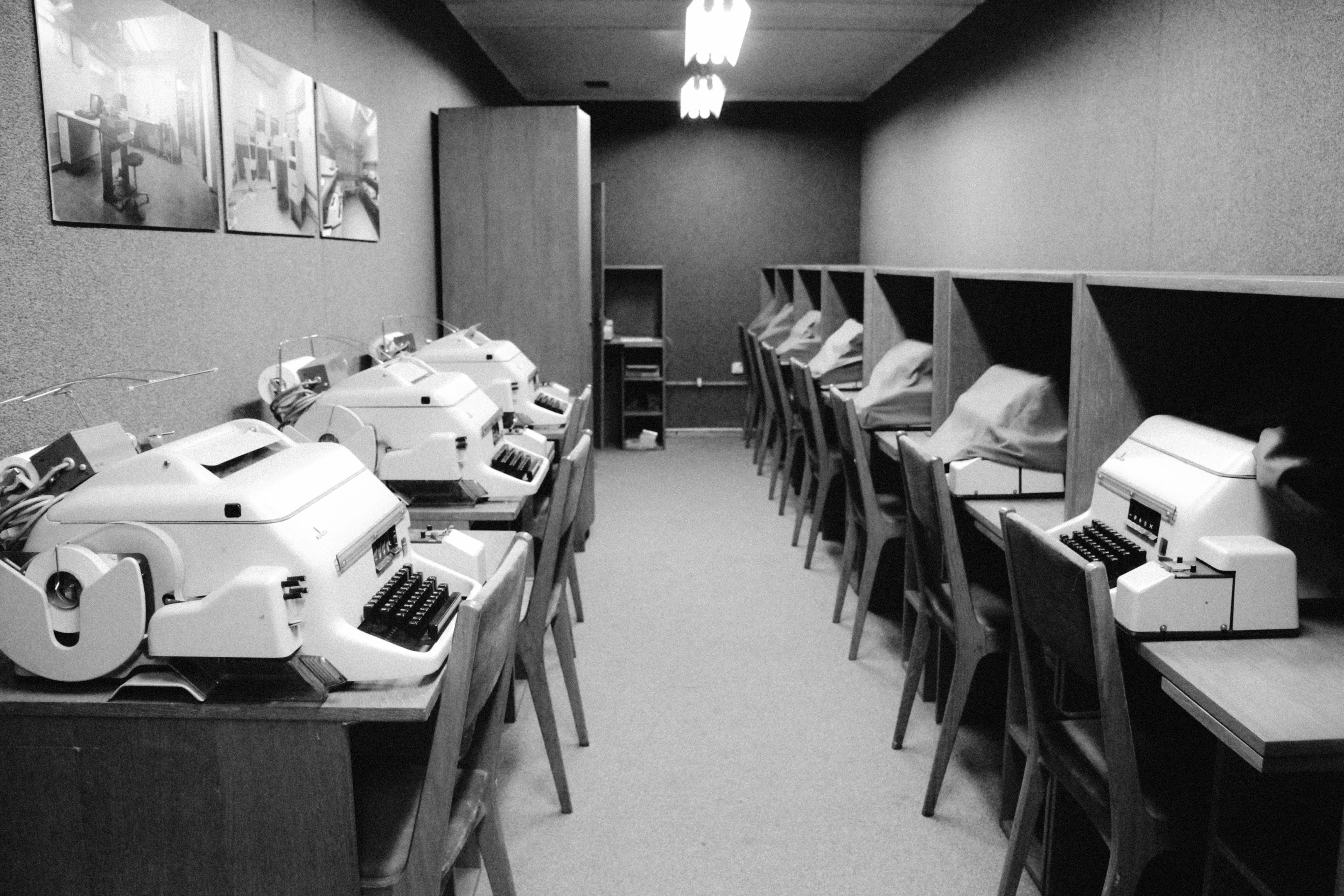

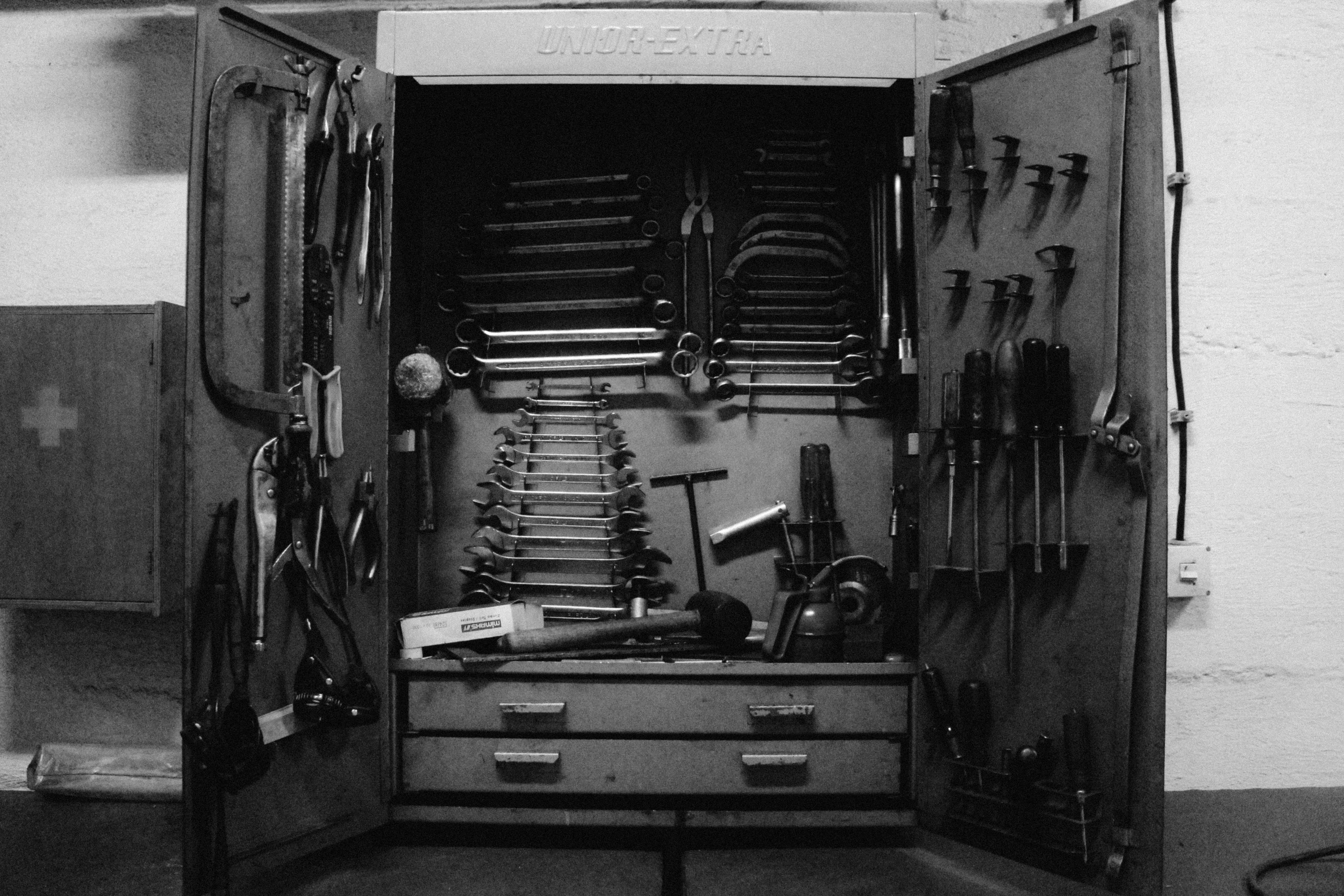

The bunker is like a labyrinth with a complex of residential areas (with more than 100 bedrooms), conference rooms, offices, and operational centers with direct phone connections to the presidents of all Yugoslavian federal republics—the “presidential bloc.” It has its own generators, water supply and air purification systems, which still work to this day. The workspaces and the dining room of Josip Broz Tito and his wife, Jovanka, along with the room of Prime Minister Dzemal Bijedić are particularly superior and larger compared to the ordinary rooms. Throughout the building, you can see pictures of the famous leader.

When Yugoslavia collapsed, just before the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbs and Croats had largely dismantled military installations in the region. In 1992, the Serbian high command in Belgrade gave the order to destroy the bunker, but a Bosnian military guard refused to carry out the order and sabotaged the operation, managing to save the bunker. Since then, the building, along with all its signs, symbols, furnishings, and instruments, has been carefully preserved.

Today, the Ministry of Defense of Bosnia is the owner of the nuclear bunker, but it is now open to the public and functions as an underground modern art gallery, welcoming a biennial of contemporary art every second year. Even if Tito never actually got to see the finished work, the impressive construction seems to serve as a massive memorial in his memory and relic of the former republic of Yugoslavia, which attracts more and more tourists from throughout the region and the world each year.

We thank Amela Hujdur from Visit Konjic Agency for the visit and translation.

titovbunkerkonjic

https://titovbunkerkonjic.com and https://bunkerkonjic.com for tours of this amazing place