The dead in Sarajevo’s Jewish cemetery cannot speak for themselves. They cannot protest the damage to which their final resting place has been subjected. David Schafer and Alastair Carr (photos) report.

In Judaism, we recite Kaddish, a prayer, to honor the legacy of a deceased family member. We do this not to speak for, but rather on behalf of, the dead, as they have lost their agency in their passing. We hope to perpetuate the soul’s ability to glorify G-d.

I wrote this article in similar fashion. The dead in Sarajevo’s Jewish cemetery cannot speak for themselves. They cannot protest the damage to which their final resting place has been subjected. In writing this piece, I hoped to draw attention to the degrading state of this historical landmark. No burial ground, no matter the faith or affiliation of its inhabitants, should exist in the conditions you will read about below.

Even in a city abundant with centuries-old treasures, Sarajevo’s Jewish cemetery stands out – for better and for worse. According to Eli Tauber, an adviser on culture and religious affairs for the Jewish community of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the cemetery dates back to at least 1630. Recent findings in once-forgotten archives, however, may show the cemetery is even older, with some burials dating back as far as 1545. Though the last burial occurred in 1966, the cemetery is still a powerful symbol of the limitations faced by the city’s small Jewish community and, even more so, of the price of war.

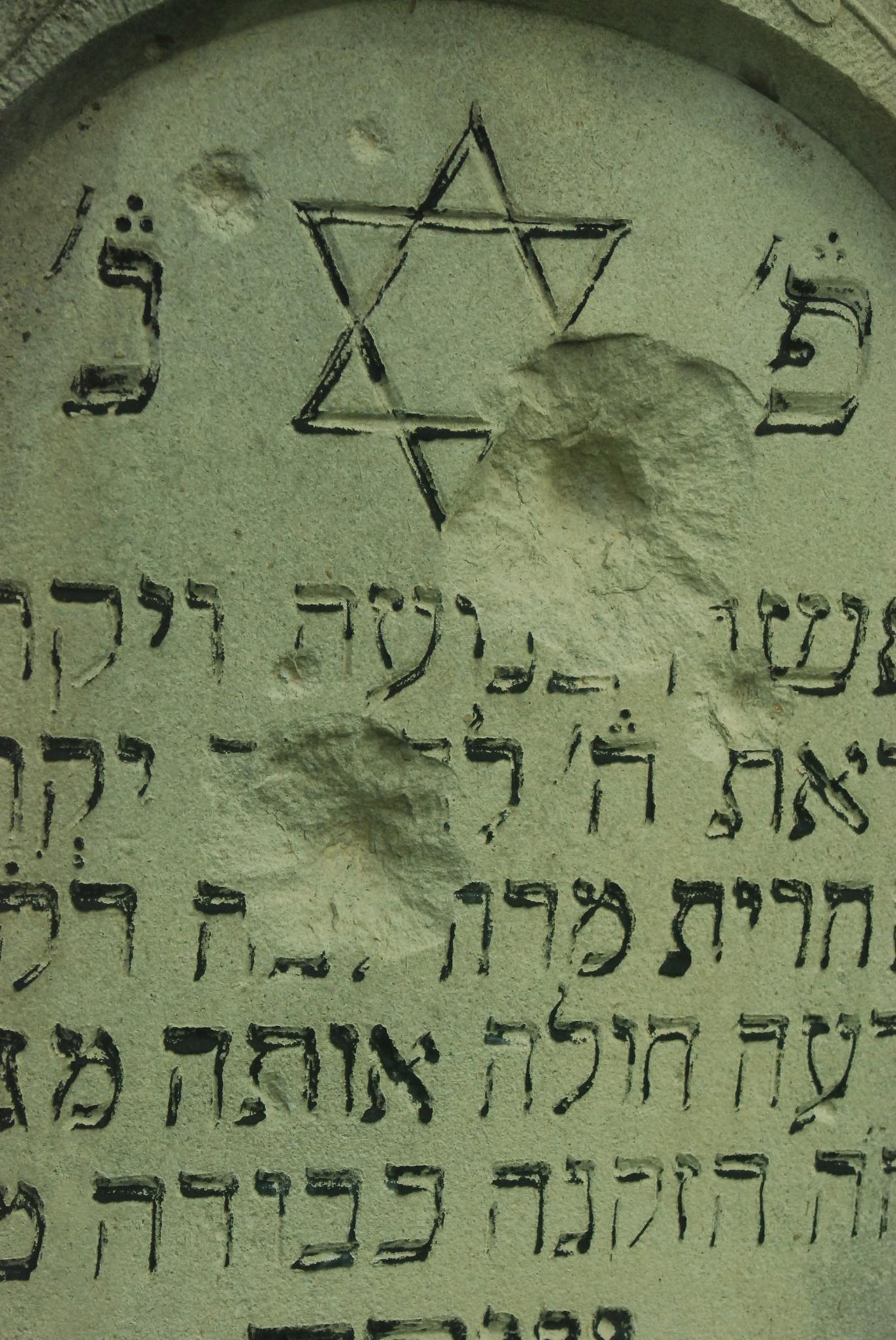

Despite its history and significance – it is, for example, the “oldest intact, burial ground of any religious group in the city” – the cemetery has remained largely neglected and its condition is rapidly degrading. Many of the tombstones are now obscured from view. Weeds have grown up and around the uniquely shaped headstones, which, according to legend, were designed to resemble the backs of crouching lions. The Hebrew and Ladino engravings of names and dates have long since faded from many of the tombstones. Garbage and graffiti are not uncommon sites, too.

Rather than malice or anti-Semitism, they represent the inability of the city’s Jewish population to renovate the grounds. Tauber elaborated that while the synagogue has an agreement with an independent company to clear and guard the cemetery, it simply does not have the money to restore the grounds to their previous state. This issue stems from a larger problem; one the community has faced since World War II.

Nearly all of the community’s property was confiscated by the occupying powers during the war and the subsequent Tito era. Much of its money was lost, and even with the breakup of Yugoslavia, the ability to reclaim property was restricted, as the Bosnian Constitution, Tauber notes, avoids the issue of restitution. Today, the Jewish community relies on donations from individuals and governments for financial support. Funds from the American and German Embassies, for example, helped to reconstruct and clean small portions of the cemetery.

Scattered soda bottles, overgrown grass and crudely sprayed green lettering aside, the most glaring reminders of the less-than-ideal state of the cemetery are the bullet holes that riddle its Holocaust memorial and many of its headstones. The newly renovated front gate, the product of a 70,000BAM donation from the German Embassy, is misleading: once inside, reminders of the Bosnian War are everywhere. During the conflict, the cemetery was among the many front lines utilized to maintain the brutal siege of the city. Bosnian Serb Army snipers used its strategic position, overlooking much of the city from Mount Trebević, “to shoot at civilians in the city.” Many of the beautiful tombstones, unique in both Sarajevo and Europe, were damaged by the fighting, their elegant structures compromised by three years of heavy shelling and indiscriminate shooting.

Even with its little money and a reliance on donations, the Jewish community is hoping to further renovate the cemetery. Tauber spoke about a group from Germany that was scheduled to come in the summer to help clear the tombstones and clean the grounds. He also excitedly discussed a plan to generate attention and educate people of all backgrounds on its history and current, unfortunate condition. With a focus on the cultural history of Jews in Sarajevo, Tauber hopes to find and unearth the cemetery’s genizah, a storage area found in most Jewish cemeteries that holds Hebrew-language and religious books. In this cemetery’s case, it has been buried for nearly 150 years.

Additionally, the synagogue is in the process of designing an exhibit on the cemetery that will be set up in the small synagogue on the grounds. Tauber is hoping to profile the uniquely shaped tombstones, distinct epitaphs d the cemetery’s role and subsequent degradation during the Bosnian War. Drawing attention to its significance and, more powerfully, its sad state is important. Focus and sympathy generate donations, which are necessary if the cemetery is to be repaired. One day, in a more perfect world, Tauber hopes for UNESCO recognition and protection for the cemetery and its historical and cultural importance. “But,” he concedes, “that’s too far in the future to think about.”

After a long pause, Tauber qualifies his previous statement. Sadly, he notes, though not without some positivity, “We can’t expect it to be better, but we can hope.”