“How does one archive or record the details of the massacres of a state that wants to hide its massacres?” Serbian director Ognjen Glavonić attempted to do just that with his latest film.

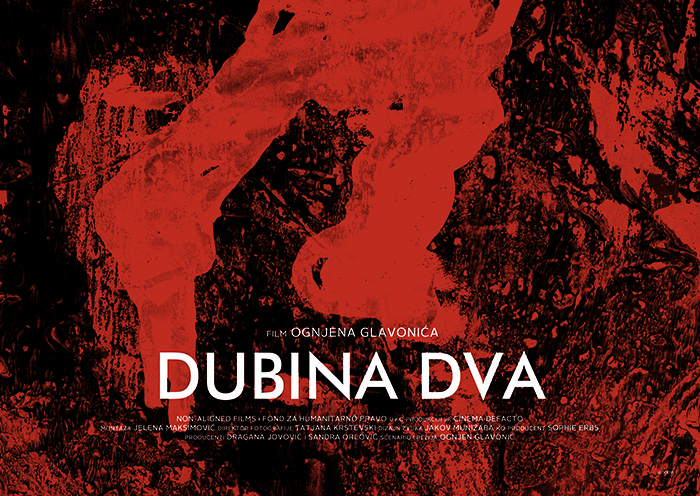

In his keynote address at the 2017 WARM Festival’s “Why Remember?” Conference, artist Vladimir Miladinović asked, “How does one archive or record the details of the massacres of a state that wants to hide its massacres?” Serbian director Ognjen Glavonić attempted to do just that with his latest film, Dubina Dva (Depth Two).

Screened in Sarajevo on 30 June at Kino Meeting Point, Depth Two (2016) is Glavonić’s first feature-length documentary. Using a combination of spoken testimonies documented by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and images depicting the locations of the crimes, the film recounts a massacre of ethnic Albanians during the Kosovo War from 1998-1999 and the transfer of their bodies to a mass grave outside of Belgrade.

This experimental documentary shows no faces, has no named characters and has no narrators. Instead, formless voices carry the audience through the narrative alongside meditative scenes that are both tranquil and eerie. While we hear the Danube lap the sides of a boat, a narrator tells us with a startling memory for detail, “I noticed a crack in the rear of the truck. I saw two human feet and one arm sticking out of the crack.”

Beginning with the discovery of a freezer truck filled with the bodies of victims, the film follows their removal, transfer, and the cover-up that followed, eventually recounting the massacre as told by both a survivor and a soldier who were there that day. Civilians discovered the truck on 6 April 1999 near the Serbian town of Tekija. After exposing its contents, the interior ministry ordered the bodies be removed and the truck destroyed as it was to be kept a state secret in order to avoid inciting additional NATO airstrikes.

The 53 (mostly) in-tact corpses and three heads were transferred to Belgrade and their belongings documented: a child’s purse with a UNICEF notebook, wooden crayons, and a little doll; a comb; a gold wedding band; and, of course, the bullets found in their bodies.

The survivor—who lived by pretending she was dead after she had been shot at least four times—describes how her family was ordered from their home and fled Serbian soldiers armed with automatic rifles before ultimately being forced into a pizzeria that was then filled with grenades and rifle shots.

All told, more than 700 bodies were relocated and buried in Batajnica, a suburb of Belgrade. Discovered in 2001 and 2002, the mass graves included women, children and elderly, all civilians. Under orders not to speak about his role in burying the bodies, one perpetrator—whose voice had been distorted for his testimony—recalled being told, “Be careful or the darkness will eat you.”

Documents recovered from the war revealed that the operation was part of a larger program—“Dubina Dva”—to destroy evidence of massacres in Kosovo. Knowledge of the program extended all the way to Milošević, whose handwriting on one of the documents states a clear directive: “no body, no crime.”

By not giving them a face, Glavonić’s conveyance of the perpetrator’s stories humanizes them—they could be anyone, any soldier following orders. By approaching the atrocities in this way, he challenges the narratives of victims and perpetrators promulgated by politicians and in history texts. From these testimonies, it is clear that the soldiers carrying out the orders were themselves, victims. One narrator describes how he was unable to fire during the massacre and was told to drink alcohol in order to relax (a common coping technique among soldiers ordered to commit crimes). Another describes the nightmares that leave his nights restless.

The crimes remain a guarded topic that many in Serbia know little about or refuse to discuss. “Everybody knows something,” artist Vladimir Miladinović said, “but they don’t know exactly what they know.” This is in part due to extended media blackouts and deliberate cover-ups of the event.

The first to report on the discovery of the truck was a local crime magazine—Timočka krimi revija (Timok Crime Review)—though its articles weren’t published until two years later. Further, the owner of the magazine, Dragan Vitomirović, died under mysterious circumstances not long after, a case that also remains unsolved.

While initial hopes that the “freezer truck case” might finally end denialism and begin the process of public recognition and responsibility taking in Serbia, this has yet to take place. In the 15 years since the mass graves were discovered, there have been no domestic prosecutions for participation in the massacre or the cover ups, despite the extensive coordination necessary for an operation of that size.

The lack of a widely known and recognized history of the events spurred Miladinović’s search for references and sources from his own knowledge and memory. To this end, testimonies of victims, perpetrators, witnesses, and those who blur the lines of those categorizations are invaluable. They must be heard and recognized, for there’s nothing worse, Miladinović says, than “to suffer, to survive, to tell, and then not to be believed because it is unimaginable.”

As a nationalist tide has risen around the world, the Balkans too have felt its pull. In the face of these attitudes gaining purchase among youths, interest in these topics and finding the truth becomes vital. Glavonić has spent years researching the massacre and the mass graves recounted in the film, and both he and Miladinović have used ICTY archives to bolster their work and understanding. While there remains no accountability and no public history of the crimes, Miladinović says, “We are surrounded by proof.” It’s just a matter of digging it up.

—

“Depth Two” was screened during the WARM Festival in Sarajevo that took place from 28 June to 2 July 2017. Organized by the WARM Foundation in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), the WARM Festival brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.