In Bosnian society, persons with disabilities are not recognized as equals and are often treated with pity or fear.

Persons with disabilities living in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) often don’t have access to certain public spaces and institutions and information is often not available in the formats necessary to accommodate persons with different types of impairments. According to the Association of Youth with Disabilities “InfoPart”, some of the main obstacles related to issues of accessibility for the visually and hearing impaired include a deficit of audio literature and materials in braille, employees in public institutions who know sign language, and audio-tactile crosswalk and traffic light systems, to name a few.

Aleksandar Dukić, whose disability is the result a rare genetic condition called epidermolysis bullosa, points out that people with disabilities need personal assistance and home care services, first and foremost, but they also need infrastructure, transportation, workplaces, and educational institutions that are adapted to accommodate their needs.

A clear strategy is necessary in order to overcome these difficulties. Infrastructure cannot be changed in a short period of time, thus, medium-term action plans must be made and executed, while keeping in mind that there are some spatial adaptations that don’t require large financial investments.

As a result of institutional inaccessibility, the disabled are often forced to choose among only those schools and occupations that can provide at least some accommodation. Schools, cultural and sports facilities and administrative and judicial institutions in smaller communities are all often inaccessible, violating a broad range of rights for people with disabilities. Hospitals are typically the most accessible kind of institution, which, unfortunately, reflects the limited societal view of disability from solely a medical perspective.

Dukić, who moved from Prijedor to Banja Luka in 2013, confirms that the conditions in smaller communities and towns are, indeed, significantly worse.

“Banja Luka is at least somewhat adapted to allow for greater mobility for people in wheelchairs, unlike Prijedor which, at this time, isn’t even 5% adapted. I’ve heard that things are starting to move forward over there, but progress is extremely slow, almost insignificant. The situation in Banja Luka is far from ideal, but at least there is some level of accessibility,” says Dukić.

He emphasizes that, although there are still a number of places that don’t have infrastructure that has been adapted to people with disabilities, the situation is equally as bad in places that do have adaptations because they are either inadequately done or their functionality is not maintained properly.

“The lift in the city center that is supposed to transport the wheelchair-bound to the supermarket, a couple of restaurants, a cafe, and the cinema, is out of order. So, in addition to not having a cinema, we, the wheelchair-bound, also don’t have a discotech. Society and our government officials seem to think that disability and illness are one and the same and that the only place we need proper access to is the hospital so that we can see the doctor,” says Dukić.

Another sign that the authorities do not care about the needs of the disabled is when cables or pipes are repaired. Companies cut the asphalt and leave it in disrepair, which further complicates the mobility of people with disabilities.

“When I see a construction company doing some work, I make sure to write down their phone number so I can call and ask them not to leave the place worse than they found it. People often comply, but they need to be told,” says Dukić.

There are a number of associations that serve as mediators between the disabled and the public institutions. The president of InfoPart’s board of directors, Vera Bošković, stresses that InfoPart continues to launch numerous initiatives aimed to increase the implementation of existing regulations that guarantee the rights of people with disabilities as equal members of society.

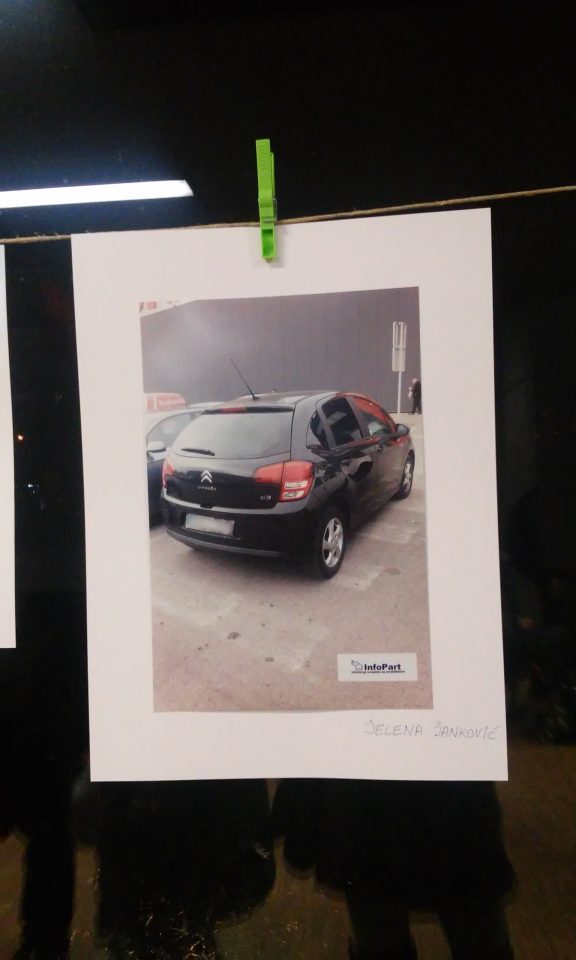

“We’ve tried to increase the chances for people with disabilities to get beneficiary group status for obtaining housing loans and housing adaptation loans. We’ve also made an effort to promote the “Don’t Stand in My Way” campaign to show drivers and legislators the difficulties caused by illegally-parked vehicles,” says Bošković.

The Balkan Diskurs Youth Correspondent Program is made possible by funding from the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).