Monuments, due to their strong symbolic meaning, give clear messages of what, whom and which promoted values should be remembered.

A culture of remembrance – that is, the relationship between a society and its past – is an essential part of every society, and historically, no society has ever ignored it. One way to remember is to build monuments and museums. Monuments become physical symbols, the purpose of which is not only to help in the process of reconciliation in a post-conflict society, but also to stand as a warning and a reminder of past sufferings so that they will not happen again.

“Monuments are indicators of the values on which society wants to rest. The importance of monuments lies in the fact that places of remembrance are right next to them. Commemorations and other ceremonies of remembrance are organized with special programs which have an impact on the formation of collective identity and form official attitudes towards history,” says Amra Čusto, historian in an interview for Balkan Diskurs.

However, monuments in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) remain a controversial topic, especially those built after the last war (1992-1995). One of the reasons for this is contemporary politics, which, in Amra’s opinion, has a great influence on creating an image of the past.

“The construction of monuments in every society is part of the politics of remembrance, which, when we talk about BiH, has been changing after traumatic war events, after a difficult war legacy, with every socio-political change, and the collapse of one and the creation of another regime. Therefore, in the discourse in which different, opposing policies of remembrance are developing in BiH, the process of constant shaping, adapting of memory and establishing a new relationship not only towards the recent past, but also the past of World War II is noticeable – and all from the perspective of the present political circumstances.”

There is also the fact that each monument is a reflection of one specific story which mostly testifies to only one event, and there is always the possibility that the “other side” sees the event in a completely different way.

“The constructed monuments reflect all the divisions of Bosnian society, and often those already constructed or those intended to be erected in memory of difficult events from the past provoke lively reactions and controversy in the public. There are numerous examples which speak of wars of remembrance. Most often, monuments are built to ‘their victims,’ which shows the lack of acknowledgment of suffering to those ‘on the other side.’ Empathy is expressed, kept and developed only within its national group, and the consequence is that the issue of remembering the 1992-95 war period is further complicated, and is the reason for the constant divided and conflicting narratives,” explains Amra.

25 years after the end of the war, memorialization in BiH is divided, even though the construction of monuments is one important step towards reconciliation, as it encourages dialogue and promotes empathy and compassion for innocent victims.

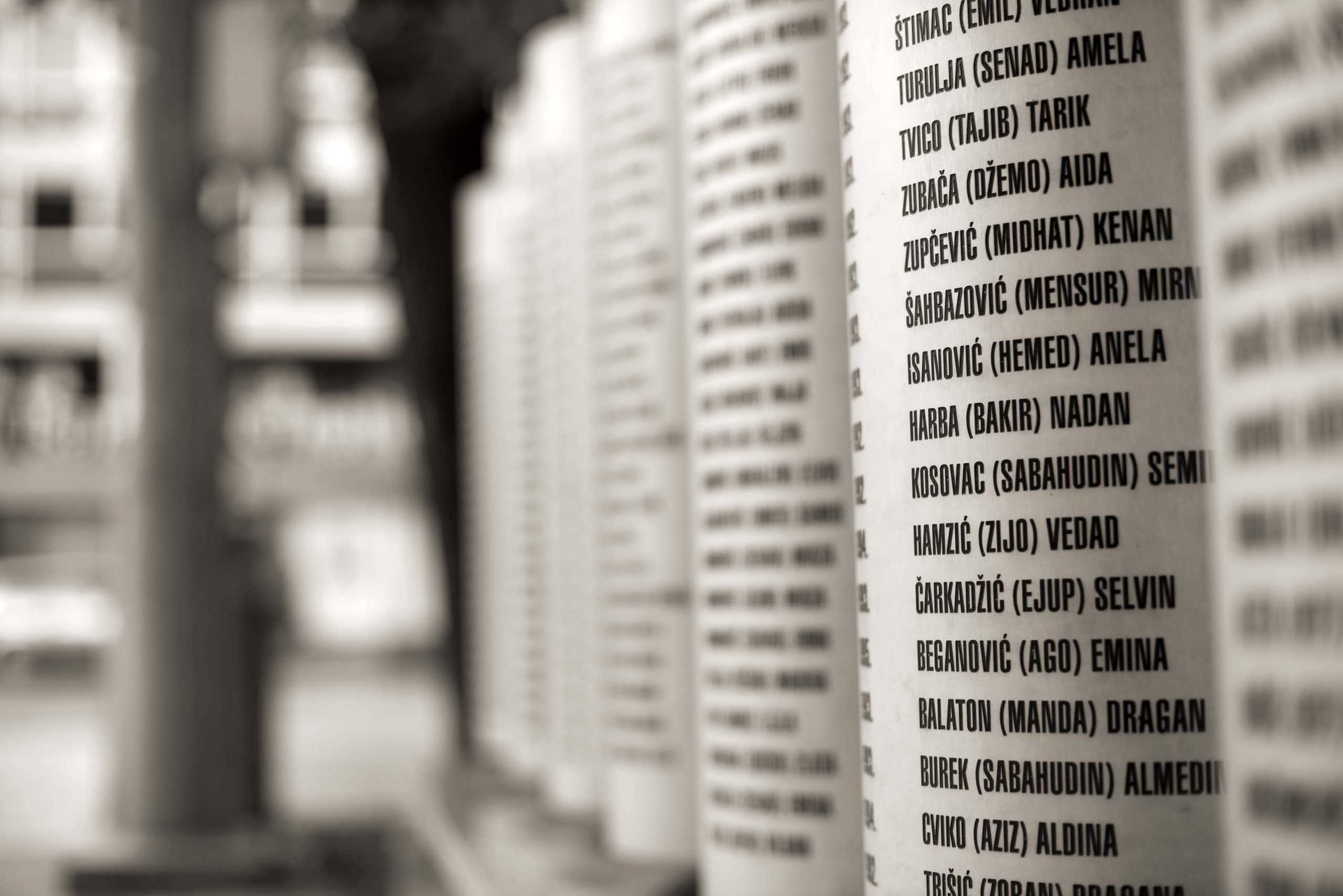

In the entire territory of BiH there are 2,143 monuments dedicated to the suffering of people during the last war, according to the list of the Central Register of Monuments. 270 monuments were built in the Sarajevo Canton, all dedicated to the suffering of people during the war. Most of them were erected to martyrs and fallen fighters, with their names engraved on plaques, but other monuments were erected to innocent victims and those who went missing during the siege.

The Memorial to the Murdered Children of Besieged Sarajevo opened on May 9, 2009, which is also the day celebrated throughout Europe as the Day of Victory over Fascism. A year after its opening, a pedestal was erected containing the names of 521 children, out of a total of 1,621 who died during this period. The monument was erected in Veliki Park in the municipality of Centar, and its creator is Mensud Kečo.

In addition to this monument, Kečo is the creator of the monument of Ramo from Srebrenica, which is also located in Veliki Park. The monument is symbolically called Nermin, come! and was made after the release of a shocking video taken after the fall of Srebrenica on July 11, 1995, in which a helpless father named Ramo, at the urging of the Serbian Army, calls on his son Nermin to surrender.

Neither Ramo nor Nermin survived, and their bones were found in 2008 in one of the mass graves near Srebrenica.

There are also “Sarajevo roses,” which are memorials to those killed by grenades that fell on the city during the siege. The roses were made by filling the grenade-made holes with red paint. They are called roses as they resemble a rose. Although most of these roses were removed over the years after sidewalks and streets were restored, some have still survived or were preserved over the years.

When asked what memorials to the memory of the victims of the 1992-1995 war represent for her personally, Amra answered that “the killed civilians, the youngest victims of the siege of Sarajevo, are among the most painful, most emotional issues from our traumatic past. The memory of them, as well as the monuments to them, should encourage us to find a more layered and omnidirectional way to observe difficult war experiences, in opening a dialogue, and in order to better understand the past.ˮ