‘… your tattoo is a symbol of your bravery and courage to remain Jewish, despite the evils you had to endure.’

“You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves: I am the LORD.”

– Leviticus 19:28 –

The above scripture explains the historical prohibition on the act of tattooing, but Jews have a much more recent and heinous association with tattoos: millions were marked, against their will, as they filed through the gates of concentration camps.[1] The numbers running along their forearms were meant to demonstrate to the recipients that they were nothing more than a number – subjects to a bureaucratic system that attempted to control every aspect of their lives.[2] Even after liberation survivors still had that blue branding. Those little numbers were silent yet eloquent witnesses to the systematic process of dehumanization to which they were subjected.[3]

A conflicted conscience befalls survivors given their own bodies disobey their sacred code. This physical paradox is exhibited in religious forums. Sites like Chabad.org and Aish.com contain the following in their ‘Ask the Rabbi’ column: ‘I have a tattoo on my left arm from the Auschwitz camp. Since the Torah prohibits tattoos, should I get it removed?’[4] Trauma of such magnitude embeds itself deep into the folds of the ephemeral generations meaning that some older Jews whose children do tattoo themselves with Jewish symbols worry that they are putting themselves at risk by calling attention to their Jewish identity.[5]

The way forward through this seemingly impassible dogma is to acknowledge that the prohibition is open to interpretation and that Judaism – like other religions – is not a stagnant thing. It can change and evolve with the times. It is this reason, this ability to adapt to monumental and absurd vicissitudes that shaped the Aishi rabbi’s reply to the aforementioned question:

‘In your case, the tattoo is not a Torah prohibition, since it was done under coercion. On the contrary, your tattoo is a symbol of your bravery and courage to remain Jewish, despite the evils you had to endure.’[6]

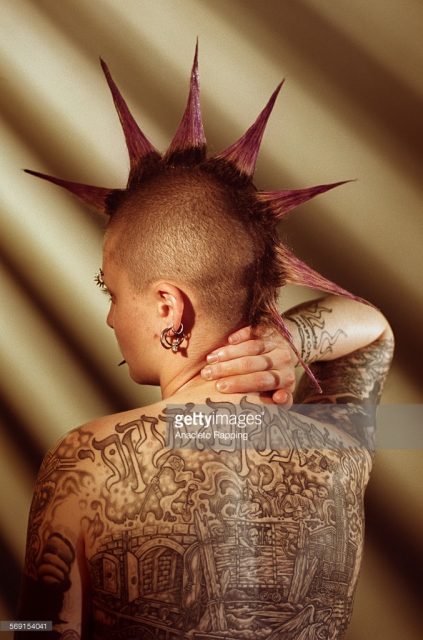

In recent years, the tattoo has emerged as a puissant emblem for some younger Jews to connect to their past and to assert their identities. Marina “Spike” Vainshtein is a renowned example of such a young person. Born in the Soviet Union, she came to the US when she was four and was raised in California. In the early 1990s, at age 18, she began styling her body with explicit Holocaust imagery. Now, more than twenty years later, almost 90% of her skin, or her ‘canvas’ as she describes it, is strewn with graphically detailed remembrance: a smoke-belching crematorium, an escaped inmate dying on an electrified fence, a can of Zyklon B (used in gas chambers) and a skeletal angel sitting on a coffin weeping.[7]

Reactions to her work have run the gamut from complimentary to fascination to utter disgust. I would argue that the latter is symptomatic of a first-time viewing, which may miss some of the more subtle elements. One such element is Spike’s individual attachment to the Holocaust— she is the granddaughter of survivors, whose portraits are a part of her corporeal gallery.[8] Another element is the degree of detail in her tattoos, not only the consummate illustration and technique but also her ink’s capacity to shed educational light on a horrific history. For example, ‘Adagio’, a piece on her right arm, depicts a man playing the violin—seemingly innocuous enough—represents the orchestra that was placed at the gates of Auschwitz to fool the herd of incoming prisoners into thinking that it was a resort rather than a death camp.[9]

With an appearance so drastically different to others, Spike believes she can open up a dialogue on history’s barbaric treatment of people, which has fastened itself to other genocidal episodes in Armenia, Sierra Leone or the Balkans. Finally, for those still questioning Spike’s choice of tattoos, they should perhaps ruminate on these words: ‘Why not have external scars to represent the internal scars?’ With this sentiment, Spike is transposing the unseen hurt from within onto the bare surface of flesh-disrobing an ostensibly ameliorating amnesia.

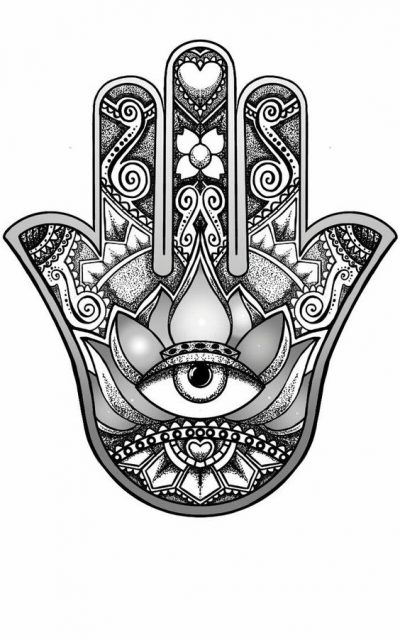

While her early pieces focus on suffering, recent additions have ushered in a revitalizing optimism. On her neck is the intricate leaf-work of a Hamsa whose intricate pattern symbolizes how ‘the Jews after almost complete European extinction took root and flourished, each leaf getting stronger than the last’.[10]

For Spike, the most important principle of her Jewish faith is the concept of the mitzvah. Mitzvoth are generally understood as ‘good deeds’ but can also be interpreted as a performed act that fulfills a commandment from the Torah. Since her tattoos are indelible and serve as a public commitment to her Jewish identity, they ironically constitute such a performance because, according to the Torah, it is a mitzvah to be seen in the world as a Jew.[11] So maybe one day even the hair-raising tattoos of the camps, those numerical nightmares that once symbolized the attempt to eradicate identity, could shift in meaning and become a heroic mark of survival.[12] How successful this may be – only time will tell.

(Cover Photo: Ian Waldie/Getty Images)

—–

[1] Yona Zeldis McDonough, ‘Marked Woman’ (7/8/13) <http://lilith.org/blog/2013/08/marked-woman/> [accessed 7/7/17]

[2] Stefany Truesdell, Jews and Tattoos: ‘Rooted in Conflict’ Harvard Divinity Bulletin Summer/Autumn vol. 43 no. 3 & 4 (2015) <https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/articles/summerautumn2015/jews-and-tattoos-rooted-conflict> [accessed 5/7/17]

[3] McDonough, ‘Marked Woman’

[4] Truesdell, ‘Jews and Tattoos…’

[5] Andy Abrams essay “Kosher Ink: The Emerging World of Tattooed Jews” in Truesdell, ‘Jews and Tattoos…’

[6] Ibid

[7] McDonough, ‘Marked Woman’

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Verena Hutter, ‘So That They Never Forget the Holocaust’ Memorial Tattoos and Embodied Holocaust Remembrance in ‘Sentient Performativities of Embodiment: Thinking alongside the Human’ edited by Lynette Hunter, Elisabeth Krimmer, Peter Lichtenfels Lexington Books (2016) p. 283

[11] Truesdell, Jews and Tattoos…’

[12] Hutter, ‘Sentient Performativities…’ p. 284