Experts on transitional justice and human rights activists predict that a fight is ahead. Only those armed with facts can stop the celebration of war criminals, unfortunately, left to the young generation as a cultural heritage.

Ratko Mladić is a war criminal. He is the former commander of the General Staff of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), a general by military rank, who was in hiding for almost 16 years and was finally arrested in Serbia in 2011. On June 8th of this year, after nine years of court proceedings, the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (MICT) upheld a verdict sentencing Mladić to life in prison for genocide in Srebrenica, terrorizing citizens in Sarajevo, and other crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995. However, disrespect for court-established facts can be seen in recent events in Serbia concerning a mural of Ratko Mladić. Despite calls to remove the mural, Serbian police banned its removal on November 9th this year, citing “security risks.” The situation is not better in Bosnia and Herzegovina, either, and only time can tell whether legal provisions banning genocide denial and other crimes will be implemented. Experts on transitional justice and human rights activists predict that a fight is ahead. Only those armed with facts can stop the celebration of war criminals, unfortunately, left to the young generation as a cultural heritage.

From the Indictment to the Final Verdict

The trial of Mladić began in May 2012 before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). After more than five years, on November 22nd, 2017, Mladić was convicted for “the worst massacre in Europe since the Nazi era,” according to the British magazine The Guardian.

He was convicted of genocide and persecution, extermination, murder, deportation, and forcible transfer from the Srebrenica area in 1995; persecution, extermination, murder, deportation, and inhumane acts of forced relocation in municipalities throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina; for killing, terrorizing, and unlawfully attacking civilians in Sarajevo; and taking United Nations (UN) hostages, as stated in the ICTY’s Trial Judgment Summary.

He committed the crimes by participating in and contributing to four joint criminal enterprises (JCEs), namely the comprehensive joint criminal enterprise, the joint criminal enterprise related to Sarajevo, the joint criminal enterprise related to Srebrenica, and the joint criminal enterprise related to hostage-taking.

He is guilty of orchestrating the murder of more than 7,000 Bosniak men and boys throughout Srebrenica, including the killing of more than 1,000 men in a large warehouse in the village of Kravica and 1,000 men near a school in Orahovac.

Under Mladić’s command, Sarajevo was under siege for 1,460 days – the longest siege in modern history, when hundreds of thousands of grenades were fired on the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina and more than 11,500 people were killed. This garnered him the nickname the “butcher of Bosnia.”

Mladić is guilty of ten of the 11 counts of genocide, crimes against humanity, violations of the laws or customs of war. His indictment was filed in 1995.

However, Mladić hid from international justice for the next 16 years. He was arrested in Lazarevo, Serbia, in May 2011. His trial began on May 16th, 2021. Three hundred seventy-seven witnesses were examined, and about 9,914 pieces of evidence were admitted. He was tried on the indictment last revised on December 16th, 2011.

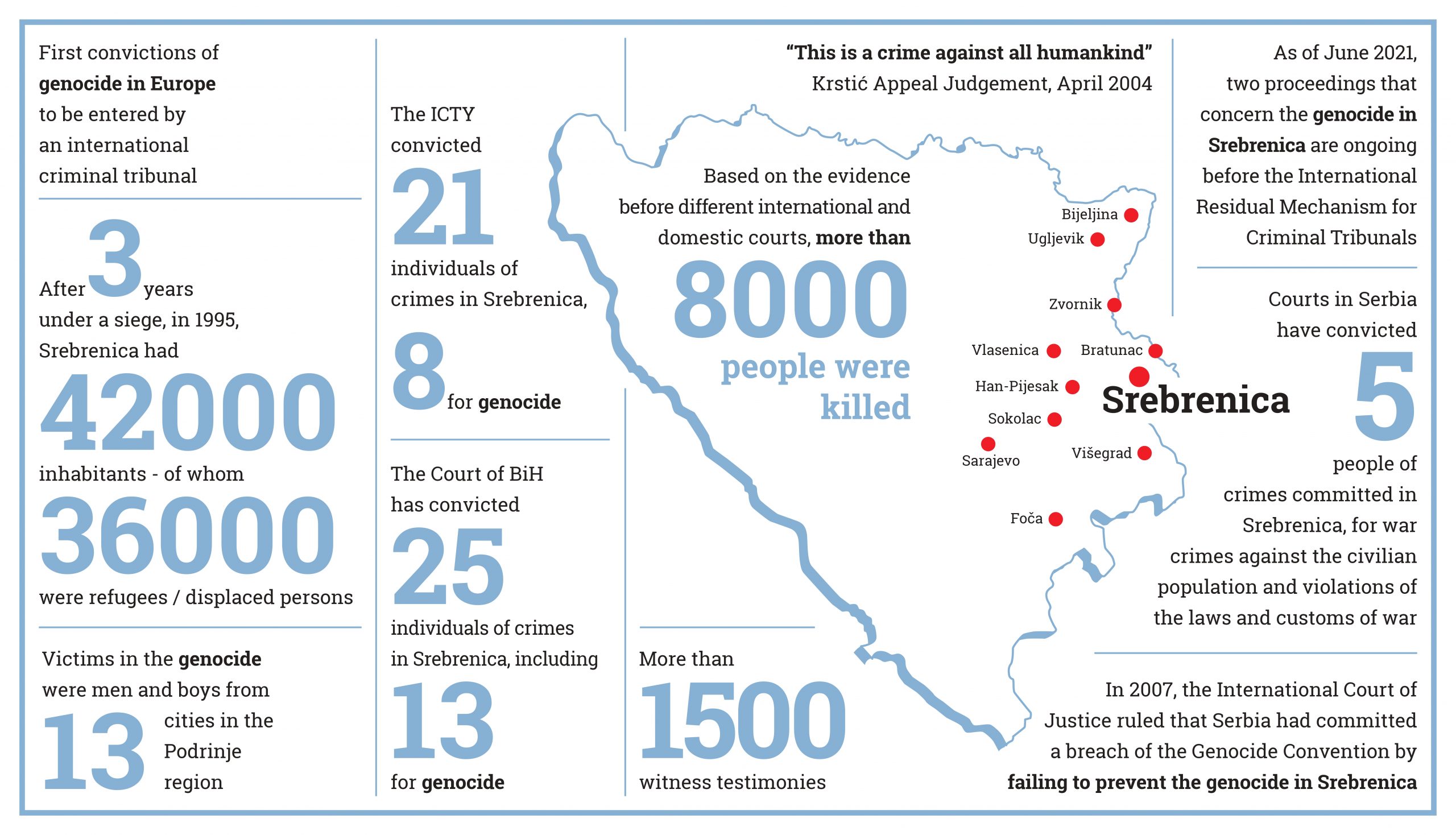

The Genocide of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica

The Trial Chamber, chaired by Judge Alphonse Orie, found that members of the Republika Srpska Army (VRS) intended to eradicate all Bosnian Muslims from Srebrenica, who represented a significant part of the protected group.

The verdict found that between July 12 and 14, 1995, members of the VRS and the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) organized transportation for approximately 25,000 Bosnian Muslims, mostly women, children, and the elderly, from the Srebrenica enclave to the territory under the control of the BiH Army, in convoys of buses and trucks. Bosnian Serb soldiers systematically separated men from the rest. Among the separated men, there were boys as young as 12 and people over 60.

The separation was aggressive. People on the buses were told that Bosnian Muslim men would come later. They never did. The Bosnian Muslim men taken from Potočari were detained in temporary facilities and later taken by bus, along with others captured from a column of fleeing people to execution sites in Srebrenica, Bratunac, and Zvornik.

The Trial Chamber found that many of these men and boys were cursed, insulted, threatened, and forced to sing Serbian songs while waiting to be executed.

Bosnian Serb forces, primarily VRS members, systematically killed several thousand men and boys.

For several weeks in September and early October 1995, senior VRS and MOI officers tried to cover up their crimes by exhuming the remains of victims from several mass graves and reburying them in remote areas of Zvornik and Bratunac.

Furthermore, the Chamber found that killings were committed in several municipalities in Bosnia and Herzegovina that constituted a crime against humanity and a violation of the rights and customs of war. It was stated that many victims were killed before, during, and after the Bosnian Serb attacks on non-Serb villages. The circumstances were terrible; those trying to defend their homes faced relentless force. Many of the perpetrators who captured Bosnian Muslims showed little or no respect for human life and dignity.

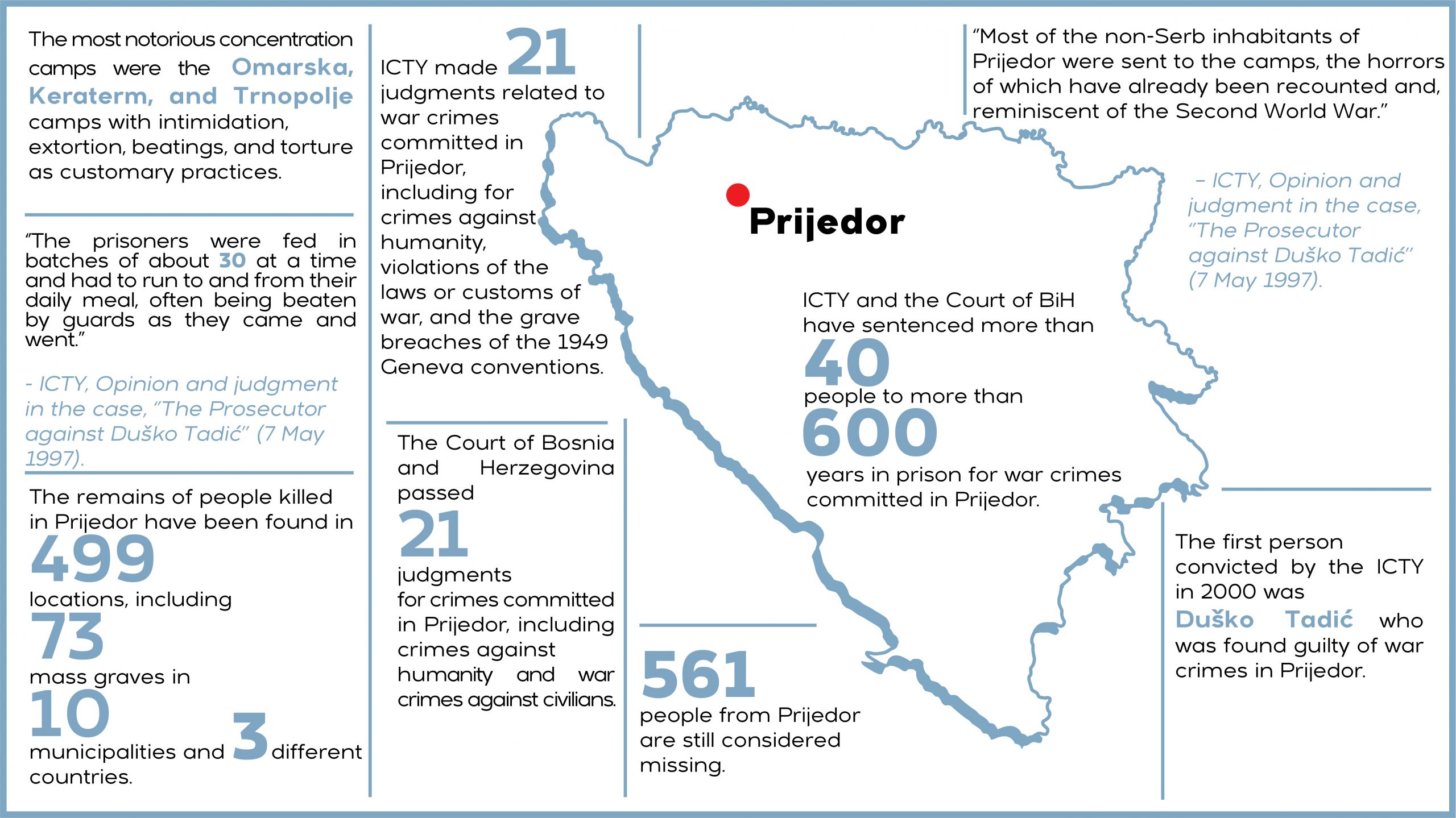

Regarding the accusation of genocide committed in six other municipalities (Sanski Most, Vlasenica, Foča, Kotor Varoš, Ključ, and Prijedor), the Chamber did not conclude that there had been intent to exterminate a significant part of the protected group of Bosnian Muslims in UN safe zone.

The Chamber found that the physical perpetrators in the municipalities of Sanski Most, Vlasenica, and Foča, as well as certain perpetrators in the municipalities of Kotor Varoš and Prijedor, intended to murder Bosnian Muslims in those municipalities as part of a protected group. However, they concluded that these victims did not constitute a significant part of the protected group. This is the only count in the indictment against Mladić for which he was not found guilty.

Furthermore, the Chamber found that deportations and inhumane acts of forcible transfer as crimes against humanity were committed in the municipalities of Banja Luka, Bijeljina, Foča, Ilidža, Ključ, Kotor Varoš, Novi Grad, Pale, Prijedor, Rogatica, Sanski Most, Sokolac, and Vlasenica.

The Chamber found that many victims had been subjected to unlawful detention and cruel treatment on political, racial, and religious grounds. In several detention camps, the conditions were appalling. There was not enough food and water, which led to malnutrition and death. Detainees were often beaten, sometimes with brass boxers and iron bars. The detainees were forced to rape each other and perform other degrading sexual acts on each other. Many Bosnian Muslim women, who were detained illegally, were raped.

From mid-May 1992 to November 1995, the VRS and the Sarajevo-Romanija Corps (SRK) deliberately fired grenades and sniper shots at Sarajevo’s civilian population, often at locations of little to no military importance. As a result, hundreds of civilians were killed and thousands injured, many of whom were shot while performing daily activities such as walking with their children, fetching water, collecting firewood, or going to the market.

The Chamber found that SRK members intended to spread terror among Sarajevo residents and that terrorism was the primary purpose of sniping and shelling. The Chamber found that members of the SRK committed murder, unlawful attacks on civilians, terrorism as a violation of the laws or customs of war, and murder as a crime against humanity.

Appeals were filed against the first-instance verdict. In detailed appeals, Mladić’s defense demanded that he be acquitted or tried again, while the Hague Prosecution requested that he be found guilty of genocide in six other country’s municipalities.

Appeals were filed before the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Courts (IRMCT), the legal successor to the ICTY. The second instance and the final verdict were passed on June 8th, rejecting the requests made in the appeals. Mladić was sentenced to life in prison for the genocide in Srebrenica and other crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, terrorizing the citizens of Sarajevo and taking UN members hostage. The verdict states that Mladić committed crimes by participating in four joint criminal enterprises:

- First, an Overarching JCE whose objective was to permanently remove Muslims and Croats from Serb-claimed territory in Bosnia-Herzegovina through commissioning the crimes charged in the indictment.

- Second, a Sarajevo JCE, whose objective was spreading terror among the civilian population through a campaign of sniping and shelling.

- Third, a Srebrenica JCE, whose objective was the elimination of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica.

- Fourth, a Hostage-taking JCE, whose objective was taking UN personnel hostage to prevent NATO from conducting airstrikes against Bosnian-Serb military targets.

Denial and Minimization

In 2011, Azra Hadžiahmetović and Beriz Belkić, members of the House of Representatives of the BiH Parliamentary Assembly, submitted the Bill on Prohibition of Denial, Minimization, Justification, or Approval of the Holocaust, Crimes of Genocide, and Crimes Against Humanity for consideration. Republika Srpska lawmakers did not support the proposal. The RS joint commission suggested that the issue be introduced through criminal law. However, that was not adopted either. The state parliament did not adopt a ban on genocide and holocaust denial in the years to come.

Only in 2021, at the very end of his mandate, did High Representative Valentin Inzko use his Bonn powers to introduce an amendment to the Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which prohibits and punishes denial of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and glorification of convicted war criminals.

“The amendment to the Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina aims to address the lack of an existing legal framework, which does not offer an adequate response to the problem of hate speech, and which manifests itself through denial of crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, even when final verdicts have already been finalized by domestic and international courts,” the Office of the High Representative said.

Anyone who publicly endorses, denies, grossly diminishes, or attempts to justify the crime of genocide, a crime against humanity, or a war crime shall be punished by imprisonment between six months and five years, which applies to both groups and individuals.

The final verdict against Mladić was not accepted in Republika Srpska. Denial of war crimes, genocide, the celebration of war criminals, and murals celebrating criminals like Mladić walls significantly impede transitional justice. – journalist’s point of view

Marijana Toma, a historian and expert on transitional justice and dealing with the past from Serbia, says few transitional justice initiatives exist, and many people deny judicially established facts.

“Now we have a complete military leadership of the Bosnian Serb army, which is basically responsible for the crimes in Bosnia, but primarily for the genocide in Srebrenica. I think that is important on a symbolic level. What I do not get, and what I see as a potential problem, is a very aggressive campaign against the court-established facts that have been established before the Hague Tribunal, and also before the International Court of Justice,” says Toma.

The denial campaign is not something new, Toma believes, because we have witnessed it unfolding over the last ten – or even 12 – years.

“A party that denies court-established facts will not just change its mind because of, you know, the verdict against Mladić,” Toma continues.

She notes that one of the key things is education, which can be seen as an example of good practice in Germany.

“What proved successful is when Holocaust education entered the official education curriculum when students and young generations could learn about it, see themselves concentration camps. That’s when society changed. I think this is the best possible strategy, but unfortunately, in our region, it can be a big problem because we have a reluctant education system or institutions that do not want to open this issue,” said Toma.

She also notes that fear prevents things from moving forward because “there is already a nationalist agenda in our curricula.”

“I do not have the right answer on how to fight genocide denial. It would be easy to say that we respect judicially established facts, but we already know that no matter how many times the Hague or another tribunal (International Court of Justice) says it is genocide, you will still have people saying, ‘but in my opinion, it is not genocide,’ not realizing that they are not qualified enough to have an opinion on it,” says Toma jokingly, as she describes the importance of the Hague Tribunal and the Srebrenica Memorial Center.

“I Consider Them All Cowards”

“If it weren’t for the Hague tribunal, we wouldn’t have a life sentence. And I think that’s important. As a historian, what is important to me is the abundance of information they have – the archive they have compiled. This is very similar to what the Srebrenica Memorial Center is doing now because they really want to have information in one place. All the information serves as knowledge for the new generations. I think it is something that can make a change in society in the long run,” said Toma.

Tanya L. Domi, adjunct assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University and an associate at the Harriman Institute, visited Bosnia immediately after the war to help implement the Dayton Peace Accords.

“As a former US Army officer, I possess utter contempt for Ratko Mladić and Radovan Karadžić, the military and political masterminds of Bosnia’s destruction. And from Belgrade, Slobodan Milošević played his hand in accelerating the disintegration of Bosnia. I consider them all cowards – to have killed more than 110,000 people in Bosnia alone. These persons are dishonorable; they are war criminals; they are sociopaths; they are beyond redemption. I also came to understand that there were many genocides carried out in Bosnia, but not all were prosecuted or investigated,” she said.

According to Domi, Ratko Mladić fought a genocidal war under the pretext of ethnic cleansing, including the mass rape of predominantly Muslim women and the siege of Sarajevo, the longest siege in modern European history.

“The legacy of these wars continues to challenge and haunt the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina and their diaspora that fled to more than 80 countries around the world. If Germany in the aftermath of World War II is an example to point to, it will take at least +50 years with hard work in peacebuilding and responsible political leadership to overcome the past that has torn Bosnia asunder,” Domi said.

Many Serbs in Republika Srpska and Serbia still celebrate Mladić as a war hero, and younger generations do not want to acknowledge the truth about the Srebrenica genocide, which calls into question whether the verdict will drastically change the minds of those who deny genocide.

Tanya shares her experience from August 1996: “I was posted to the regional office of the OSCE Mission to BiH in Sokolac, and on number of occasions, I witnessed likely Mladić’s and Karadžić’s motorcades travelling at high speed with flashing lights on the side roads of Eastern Bosnia countryside – this was the heart of war crimes denial, located closely to Pale, the operating Bosnian Serb capitol during the war. It would not be until the British and French SFOR troops began arresting war criminals in 1997 before Mladić and Karadžić completely disappeared from the sovereign territory of Bosnia. Serbia handed over Radovan Karadžić to The Hague tribunal in November 2008.”

In retrospect, she says, the UN did not serve in the interests of the ICTY by funding an ongoing communications project in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia.

“By failing to engage in standard public affairs practice, the ICTY has lost a difficult battle by failing to effectively shape public opinion on the need for trials to hold war criminals accountable for horrific war crimes. It was a significant missed opportunity. At a time of belated leadership, High Representative Valentin Inzko took action to impose amendments to the BiH Criminal Code in line with his largely underutilized Bonn powers approving sanctions for conduct glorifying convicted war criminals who committed genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes,” said Domi.

This new law, in her opinion, gives human rights defenders and democratic activists the opportunity to improve the rule of law while facing hate speech.

“To make this law manifest will be an arduous undertaking by prosecutors, lawyers and human rights advocates and defenders. The international community should aid by funding education campaigns to the Bosnian public. Training and education about the new amendments to the BiH criminal code should be liberally distributed and the international community should strongly support such efforts by providing funds and hosting events about the important application of the new laws to seek accountability for genocide denial,” Domi explained.

Domi mentioned that the Srebrenica Memorial Center in Potočari published a report on the denial of genocide in Bosnia and the wider Balkan region for 2021.

“Armed with documented truth, now is the moment to pursue those who deny the most heinous crimes committed in Europe since World War II. Many Bosnians feel there has been little accountability because so many perpetrators have not been brought before courts and prosecuted for their crimes. To brazenly deny these crimes, is not only wounding but insults the pervasive suffering by the survivors. Thus, the new genocide denial law offers another avenue to accountability that is more than deserved by the Bosnian public and especially for the thousands of victims whose lives have been changed forever by the consequences of the war,” concludes Domi.

The Cultural Heritage of Celebrating War Criminals

Unfortunately, celebrating war criminals has often been inherited by younger generations in the region. Young people are often exposed to ethnonationalist narratives at home and as part of their formal education. The recent around-the-clock police protection of Mladić’s mural in a trendy Belgrade neighborhood only reinforces the celebration of the war criminals. Protestors who wanted to remove the mural on November 9th, the International Day against Fascism and Anti-Semitism, were prevented by Serbian police and Mladić supporters. This was followed by numerous clashes during protests led by activists who said they had the permission of the communal police to remove the mural. However, the Interior Ministry concluded that such action could lead to disturbances of public order and peace.

Marko Milosavljević, a program coordinator at the Human Rights Initiative of Serbia, explained how the conflict between the state and activists escalated.

“As the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, we wanted to mark the International Day against Fascism and Anti-Semitism together with the residents of the surrounding streets and our guests from other countries by removing the mural of Ratko Mladić. As a reminder, the tenants of the buildings where this mural is located received an order from the communal militia of the municipality of Vračar to remove it. However, although the housing community initiated the removal, no public or private company accepted the job. That is why we have taken on the responsibility to organize a public gathering and try again to find a company that would remove it,” said Milosavljević.

When they found professionals who would remove the mural, he stated they were banned from the rally, which intimidated both the company and the tenants.

“Since the gathering was banned, despite citizens’ attempts to protest by partially damaging Mladić’s mural, the entire area has become a zone of lawlessness because there are a group of hooligans who control the movement of residents and disturb public order and peace. However, the removal of Mladić’s mural remains the city and state’s obligation. It is our right to demand that because the removal of that mural will open space for an inclusive culture of remembrance in Serbia, where the victims of Mladić’s army from Prijedor, Sarajevo, Srebrenica, and Foča will be respected,” Milosavljević said.

Milosavljević explained that the denial of genocide and other war crimes and the celebration of war criminals is present in Serbia: “The initiative to remove the monument to Mladić has exposed what we have been warning about for years, and that is the celebration of war criminals in and by Serbian institutions. That is why they constantly deny genocide. If, for the Prime Minister of Serbia, genocide is a misunderstanding, and, for the President of the Parliamentary Committee on Justice, July 11th is ‘the day of the liberation of Srebrenica,’ then it is clear why a mural becomes more than just a mural…it becomes a monument to Mladić.”

However, he points out that a sufficiently loud minority in Serbia does not agree that the image of a war criminal should be an image of society in Serbia. He also cites citizens’ interventions to remove graffiti and place symbols of remembrance for Srebrenica genocide victims.

Due to the nature of their work, there was also vandalism on the organization’s premises: unknown hooligans graffitied their property with various vulgarities. This puts great pressure on activists who want to fight the system based on ethnic divisions. However, Milosavljević says that “there is pressure, but it is negligible in relation to the need to do our job.”

These events also affect the younger generations who grow up hearing hateful narratives.

“The extent to which the narratives of denial are great can be seen by the fact that even after 25 years of war and genocide, new generations have been pushed into the lobby for a new war by threatening to form a new Army of Republika Srpska,” Milosavljević concluded.