The citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) know well that war is the worst circumstance that can befall a nation. The people of BiH could not avoid the unfortunate events from 1992 to 1995.

However, these events did not extinguish the drive of educators to work together in the most difficult moments and to imagine a better future again, despite all the hardships of war.

In Bugojno, educators were local heroes. Instead of weapons, they were armed with pencils. They are the “heroes from the shadows” because, during the war, they tried to establish a way for children to have access to education and lead those young people affected by the war down the right path.

One such teacher from Bugojno is Edin Bevrnja, who first started working in the school in 1991/1992 in the nearby village, Vučipolje.

“At the beginning of the war, I was about to start my second year, when I was hired to finish the 1991/92 school year in the village of Vučipolje in Bugojno due to the sudden school’s lack of teachers. After almost a year without teaching during the war, in April 1993, the teaching process began again, which was held in the so-called ‘checkpoints,’ i.e., houses or business premises. This situation lasted until 1994 when the students finally moved back into the school building,” Edin describes.

He says that it was very difficult to work during the war, and it was particularly challenging because everyone was full of patriotism because of their struggles. Therefore, classes were organized by the teachers and people from the local communities where the checkpoints were located.

“We were also janitors. We took care of heating, cleanliness, locking the rooms, putting foil on the windows if the glass was broken. Coming and going from the school building was in and of itself extremely demanding, as there was often a danger of shelling. As few people had a car and fuel, we mostly went by foot or bicycle. Of course, there was no talk about the school board. The only thing we sometimes got were certain foods, like flour, oil, and the like.”

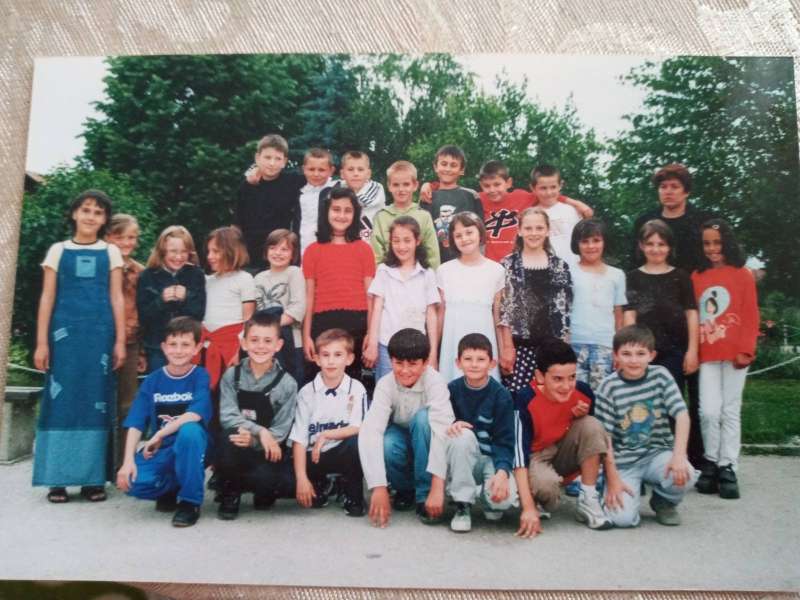

In addition to the rural school in Vučipolje, Edin also worked in the rural schools in Odžak, Hum, and Gračanica. After the war, he graduated from the Pedagogical Academy in Mostar. He continued to work in the village school in Odžak until 1998 when he transferred to the Third Primary School in Bugojno, where he still works today. When asked how he coped with fear for his life and the lives of his students, he answered: “Fear was present at every moment during the war, but while teaching you do not feel it, you defy war with your work.”

He also recalled some anecdotes from his teaching days at Odžak. During that time, first graders would come to school alone and give information about their names and the name of their parents. So, when one boy was asked, “What’s your mom’s name?” he answered, “Mujo’s wife” (BCS: Mujinica; most often in rural areas, women were not called by their names but by the name of their husband in female form). He says today, he meets his students every day on the streets of Bugojno and that he remembers many beautiful moments with them.

“These meetings are always cordial, with a smile, and when I meet those who are no longer in Bugojno, there are hugs.”

Another Bugojno woman who has dedicated her life to education is Dušanka Bujak, a now-retired teacher. Dušanka graduated from the Teachers’ High School in Sarajevo in 1971, which is now the Obala High School.

“After 16 years of working in Lug (local community), I moved to Vojin Paleksić School, which is now the First Elementary School in Bugojno, where I worked for 41 years and then retired.”

She recalls difficult times for teachers and how they were forced to make textbooks from “notebooks” because they did not have any textbooks.

“I’ve always thought about how the children will go home. I can protect them in the building, but how can I send them home and make sure that nothing happens to them? I was just waiting for an hour or two to see if a grenade would fall. That would be the hardest thing for me. I was not afraid for my life because no one ever warned me about anything,” says Dušanka.

She says the children would carry a log in their backpacks next to the books to burn at school for warmth, and the director would bring chalk in his pocket. Classes were interrupted for three, five, or ten days while the shelling lasted and then resumed, and they always tried to make it through a year so that the students could pass on to the next grade.

“During the war, I quit when two schools were formed in one school because I could not decide which school I would teach in. Both schools requested that I work for them, but I refused until after the war when the Bosniak school remained,” Dušanka recounts.

Dušanka emphasizes that she has never had any problems with anyone based on their ethnic and religious affiliation.

When asked about the most difficult moment in her teaching career, she singles out when they were ordered to make a list of students by nationality in 1992.

“I couldn’t force myself to write down the number of Serbs, of Croats, of Muslims. Someone from the school administration wanted to have the list. That’s when I saw that something ugly was happening.”

She left Bugojno for Novi Sad in 1994 to follow her parents since classes were suspended for five to six months due to the bombing. She ended up only staying there for one month when she heard that her colleagues had started working again. She immediately contacted the school principal to ask if she could return to work. She returned in April 1994 and worked until September 2012.

Today, she sees more parents than the students themselves because, as she says, they got “lost.”

“They usually greet me when they see me because I’ve always taught them that and asked them to do that. If you are a cleaner, a merchant, you are still a child to me, just like my own. There is Dr. Jusić, who never missed calling me on a holiday, asking if I needed anything. There are such examples.”

She also tells us how a young Croat boy she babysat saved them during the war. Since his family is from Split, they came to Bugojno to the funeral, but in the meantime, a war broke out, and she stayed to look after him.

“We collected sugar and flour, and I made syrup-drenched pastries [BCS: hurmašice] because it was his birthday. We were all in the same apartment because it made us feel safer. I put the cooking pan on the table, and we sat down. When the shelling started, he shouted, ‘quick, to the basement!’ We all went down right away, and nothing was left of the apartment because of the destructive shrapnel shells. Today, he is married and lives in Vienna,” says Dušanka.

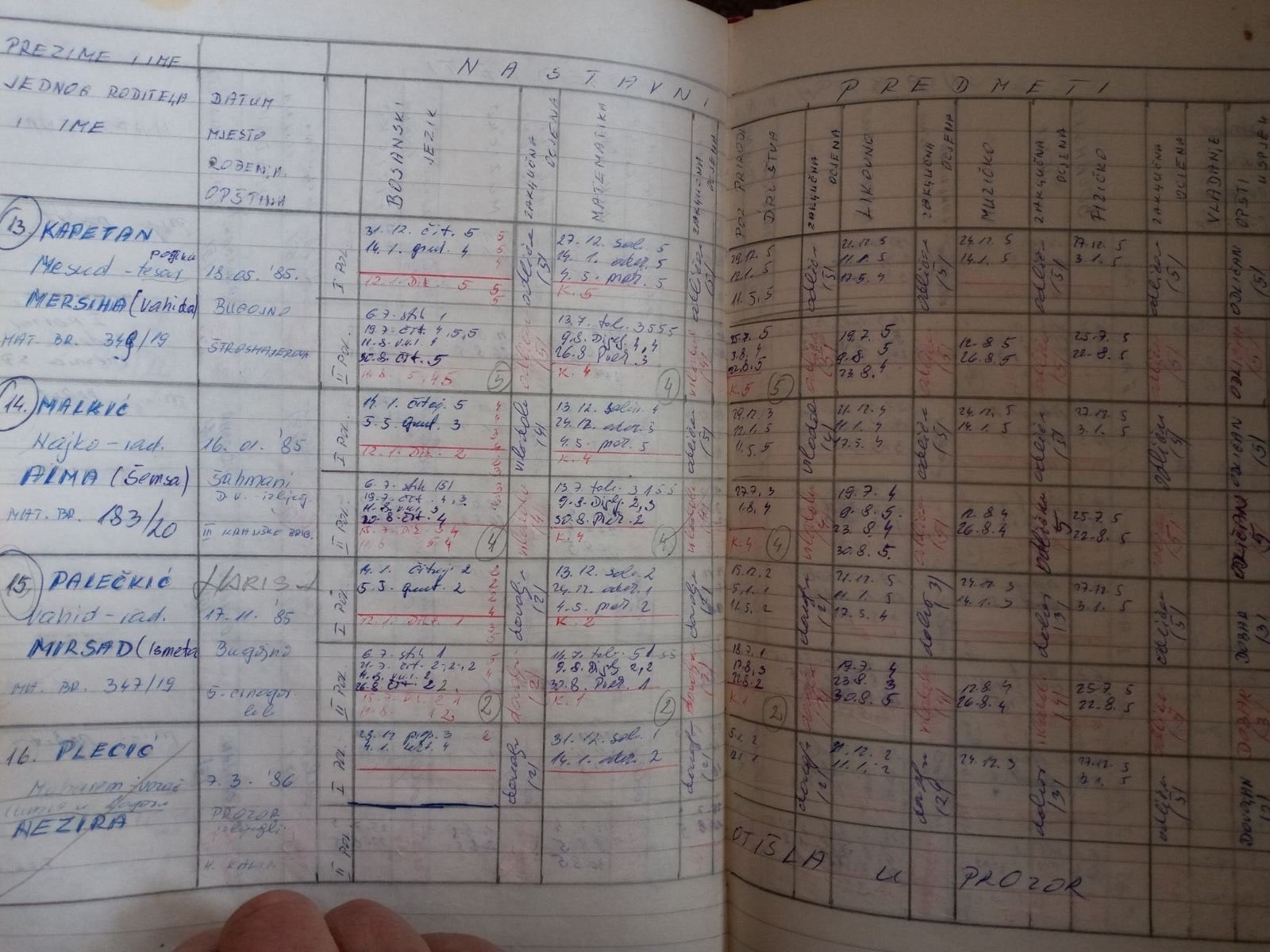

“I did not feel like the ‘other.’ I am a human and nothing more,” concludes Dušanka, who had a class book, but could not find it after the war. Nevertheless, what remains are memories, heartfelt goodbyes, and school desks full of history.