On July 14th, 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers shot Mevludin Orić at the Orahovac execution site in Zvornik Municipality – one of several locations where mass executions were carried out during the genocide in and around Srebrenica.

The body of a slain relative fell on top of Orić, who was unconscious at the time. When he regained consciousness, he wandered through the forests for days, hungry, thirsty, and afraid. He eventually managed to reach the free territory under the control of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). After 27 years, he is still willing to talk about what he survived to ensure that the Srebrenica genocide is never forgotten or repeated. His story teaches a valuable lesson.

As the Srebrenica enclave was falling to the Bosnian Serb Army, a column of 15,000 Bosniaks set out on a journey of hundreds of kilometers through the woods to Tuzla, the nearest free territory. As mostly able-bodied men, they knew that staying in the UN headquarters would be equivalent to suicide. They grasped onto the last straw of hope, which was to march through the forest. Archival footage from July 1995 shows the men and boys setting off into the woods. Some are waving to the camera, while others appear to be staring into a void. Living for more than three years under siege in deplorable humanitarian conditions had taken a visible toll on them. Yet, the will to survive is written all over their faces.

A mere 3,000 of those who embarked on the journey came out of the woods alive, some only after months of living in caves, evading Serb patrols. The majority of the men were either killed in ambushes or captured by Serb soldiers and taken to execution sites. Only a handful survived the mass executions that followed. Mevludin Orić was one of them.

“We didn’t even know what nationalism was”

Orić was born in Lehovići, a small village near Srebrenica. His family owned some land and earned the majority of their money from growing tobacco. He recalls having had a normal childhood. When asked whether there were any problems with the local Serbs, he is quick to say no. In his own words, “We didn’t even know what nationalism was back then. We were like one people.”

Although he has positive memories of the past, the ghosts of the genocide still haunt him. Talking about his childhood, he struggles not to mention the impact the genocide has had on his family. “Of the 33 men who were killed from our village, 25 were my relatives.”

After moving to Zagreb briefly at the start of the 1990s, he returned to Bosnia in June of 1992 when his daughter was born. After arriving in Tuzla, he set off to Srebrenica on foot. “I will see my daughter or die trying,” was his only thought. Two months later, he reached Srebrenica.

“Nobody believed I was still alive,” he recalls. “They all thought I’d died in the woods.” Upon his arrival, he didn’t have much time to rest as the local war hospital was in dire need of medical supplies and a surgeon. Somebody had to go to Tuzla to pick up the surgeon and the medications and bring them back to Srebrenica safely. Since Orić knew his way around that territory, he agreed to go. Leading the way, he set off for Tuzla along with three other men. They collected the surgeon and the supplies and returned to the besieged enclave safely. This heroic deed surely saved countless lives.

Just a Gram of Salt

Orić and his family lived on the outskirts of Srebrenica which meant that they were able to live off of the food they grew. By the spring of 1993, however, wheat, corn, rye, and oats were depleted. There was hunger on a massive scale, and people began to starve. Still, he always tried to help when people came knocking on his door, asking for food. “You give what you have. I could never turn someone away. I just couldn’t,” he says.

This and many other problems should have been solved with the arrival of UN protection forces. On April 16th, 1993, the Security Council passed Resolution 819 which declared the Srebrenica enclave a “safe zone.” Notably, it was not designated a “protected zone” – a distinction that would be shown to have massive consequences in 1995. “The shelling stopped, and some humanitarian aid started coming in. But I never trusted them. They sent too few troops to really defend the enclave. I never believed in them.”

Orić was right. Not only did the UN fail to deploy a sufficient force to the enclave, they also never intended to protect it. The key sentence was that the safe zone “should” be free from any armed attack. This vague definition of the safe zone left room for different interpretations based on political convenience. “After all, everywhere in the world ‘should’ remain safe,” war correspondent Adam LeBor wrote in his book Complicity with Evil.

The Death March

When it became clear that the UN troops would not stop the Serbian soldiers led by Ratko Mladić, thousands of refugees gathered in front of the UN base in Potočari. Those who did not trust the UN decided to go through the forest. The column formed in Šušnjari, a few kilometers from Srebrenica. “When I saw the mass of people, instantly knew that at least half was not going to survive. I knew the way. I knew how dangerous it was“, remembers Orić.

The first ambush in Kamenica was the last time he saw his father. Close to 500 people died during that ambush, showing to the men and boys that this was not going to be an easy march to Tuzla.

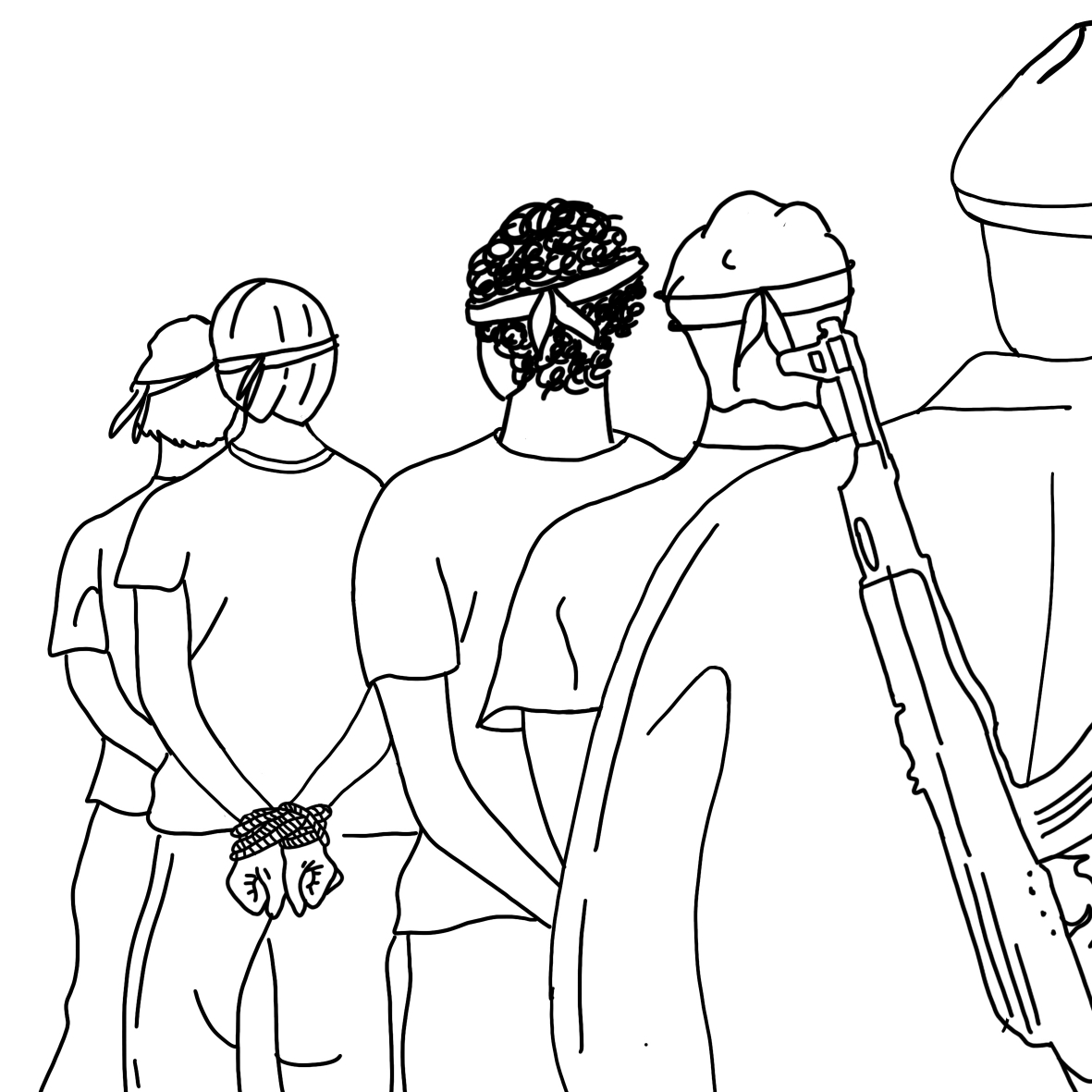

On July 13th, Orić was captured. He was first taken to the Vuk Karadžić school in Bratunac, where he and others had to spend the night sleeping in a bus. The next day they were blindfolded and brought to Orahovac, a village near Zvornik.

Orahovac was one of the largest mass execution sites of the Srebrenica genocide. The judicial verdicts of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the Court of BiH have established that members of the Army of Republika Srpska, including soldiers of the Zvornik Brigade, participated in the shooting of men on July 14th, 1995, near the school in Orahovac. The Zvornik Brigade assisted with the executions as well as the transportation and burial of corpses in mass graves. Later, they would also exhume and move the bodies to secondary and even tertiary mass graves.

“I was standing next to my cousin Hariz. He was sure that they would kill us. Before I could contradict him, they started shooting at us,” recalls Orić with tears in his eyes, remembering the most horrifying moment of his life.

“He was shot right away and fell on top of me. I felt the life go out of his body as he shivered for a couple of seconds and then died.”

According to Orić’s testimony, while he was lying among the dead, he heard Bosnian Serb soldiers insulting the dead, cursing their “Turkish mothers” and saying that they were “best dead.” One prisoner managed to escape, and he heard a soldier complain that the operation wasn’t done properly because there were survivors. The soldier then shot one man in the head and shot Orić’s cousin once more.

Orić was unconscious under the body of his cousin, and Serb troops didn’t notice that he had survived. He stayed like that all night. “I was so hungry, thirsty, and tired. At this point it wouldn’t have made any difference if they killed me. I didn’t care,” he remembers.

He was woken up late at night by rain. When he looked around, he saw a meadow full of dead bodies. Together with another man who had survived, he ran into the woods. It was not until July 21st that they arrived in Nezuk, free territory under ARBiH control.

“I felt joy and sorrow at the same time. Joy because I had survived, I had made it out. But sorrow because I kept thinking about my family. The days went by, and I was thinking that they would show up. But they didn’t. At one point you just have to realize that they won’t come back.”

Seven bones from the body of Orić’s father were found in three different mass graves. His brother’s body was found and buried at the Srebrenica Memorial Center in Potočari.

Living with Trauma

Today, Mevludin lives in Iljaš, a town on the outskirts of Sarajevo. Although he tries to lead a normal life, his trauma follows him at every step. Memories of the mass execution remain with him constantly. He suffers from debilitating anxiety and struggles to find work.

Nevertheless, he is still determined to tell his story, even though he must relive his trauma every time. In this way, he contributes to ensuring that the crimes committed during the Srebrenica genocide are never forgotten.

The exhibition “In the Footsteps of Those Who Did (Not) Cross,” which is on permanent display at the Srebrenica Memorial Center, thoroughly thematizes the Death March during the Srebrenica genocide through video testimonies, court documents, and authentic artefacts recovered from the woods by the research team of the Memorial Center.