Long before July 1995, when they witnessed the destruction of their own community in the only recognized genocide in Europe after the Second World War, they had learned about the Holocaust. This was confirmed by Munira Subašić, the President of the Movement of Mothers of the Srebrenica and Žepa Enclaves Association, whose son and husband were among the more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys killed by Bosnian Serb forces in July 1995.

For European Jews and Bosnian Muslims, analogies between the two atrocities often feel inescapable. On the eve of the 28th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, however, Jewish and Muslim leaders gathered at the Memorial Center in Potočari not to engage in comparative suffering, but to promote solidarity.

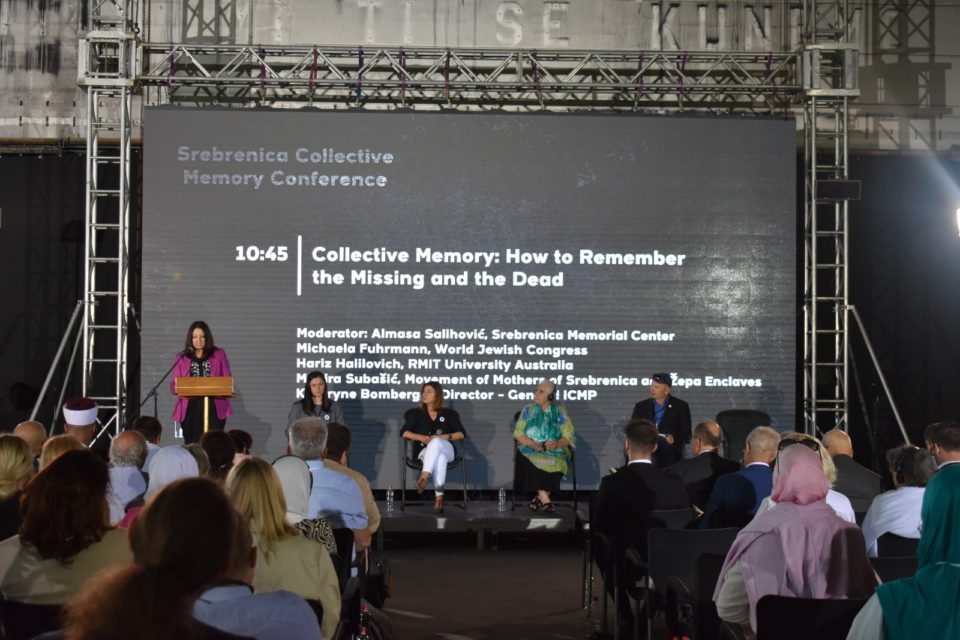

The gathering took place on July 10th, as part of the “Srebrenica Collective Memory Conference,” organized by the World Jewish Congress (WJC) in partnership with the Srebrenica Memorial Center. In what Daniel Radomski, the Head of Strategy and Programs, described as a “strong signal” of commitment to interfaith dialogue, the WJC decided to send 18 delegates from their global leadership branch, the Jewish Diplomatic Corps. The day-long event, held at the former headquarters of the Dutch UNPROFOR Battalion in Srebrenica, featured panel discussions on preserving collective memory through education, combating genocide denial and distortion, and addressing future extremism throughout Europe.

“We thought that horrific experience [the Holocaust] would never happen again,” said Hasan Hasanović, who, at age 19, fled Srebrenica with approximately 10,000-15,000 other Bosnian Muslim men and boys. “It happened again, not on that scale, but it happened to 100,000 people some forty years later.”

Hasanović was one of only 3,500 who survived the grueling 100-mile trek to Muslim-held territory. In the aftermath, he was connected with Holocaust survivors in the UK to discuss trauma. As the current Head of Oral History at the Srebrenica Memorial Center, Hasanović was given a set of oral history guidelines from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as a starting point for his own project, through which he collected 521 personal testimonies in less than four years.

The theme of collective, active, and preventative remembrance resonates strongly in a community still struggling to bury their dead. As the July heat bore down in Srebrenica on Tuesday, thousands gathered at the ever-expanding Memorial Center cemetery for the burial of the remains of 30 genocide victims identified by the International Commission for Missing Persons (ICMP) through DNA analysis.

In an interview with Balkan Diskurs, ICMP Director Kathryne Bomberger said that identifying the 40,000 individuals missing across the former Yugoslavia has the power to “ensure that the state itself takes responsibility — not just for the healing process but for ensuring the justice which contributes to peace.”

That justice has been on hold in Srebrenica for 28 years, as families wait for the remains of their loved ones, which are typically scattered among multiple mass graves, to be found. In a coffin, where one would expect a complete body, Subašić buried two small bones of her son, Nermin, who was murdered at age 16. The bones were found in graves 25 kilometers apart.

In Srebrenica, the lessons of the Holocaust are “tangible in a way that really can’t be experienced anywhere else,” Radomski said. “What they [the Mothers of Srebrenica] are doing here, on the ground, while still awaiting the burial of their children, is astounding.”

For the Jewish leaders in attendance, many of whom are direct descendants of Holocaust survivors, the conference opened a meaningful door for interfaith dialogue.

WJC Executive Committee member Efrat Sopher said that the type of “informal bridge-building” she experienced “wouldn’t happen any other way” than being physically present to support the Bosnian Muslim community at a painful time.

As a descendant of Sefardi Jews, Sopher said, those conversations are critical to establish trust: “Jews have lived in Muslim countries side by side beautifully. But there were also times when Jews were expelled from various countries within the Middle East. It’s important to commemorate and to share those experiences.”

As popular refrains of “never again” confront dead-ends amidst what some have labeled an “age of genocide,” part of that exchange is the simple knowledge that “it didn’t happen only to us,” Jewish journalist and activist Konstanty Gebert said.

Panelists denounced not only atrocities of the past, but ongoing genocide denial which pervades the present. The Srebrenica Memorial Center produces a report each year chronicling instances of Srebrenica genocide denial throughout the public media space. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, the number of documented cases surged from 234 to 693. An epidemic of Holocaust denial has plagued the Jewish community, too, which witnessed a 36% increase in antisemitism between 2021 and 2022 in the US alone.

Back in July 2021, Vice President of the World Jewish Congress, Menachem Rosensaft, had penned an extensive open letter denouncing Gideon Greif, a prominent Israeli historian who specializes in the history of the Holocaust, for his role in a report sponsored by the Republika Sprska government which presents Muslim Bosniaks as having “brought the genocide upon themselves.” As the son of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen survivors, Rosensaft drew a direct comparison between what he labeled the “Greif Report” and Joseph Goebbels’ justification of the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policies.

At a time when political leaders “speak more the language of national identity than faith,” said Friar Franjo Ninić of the Franciscan Monastery St. Peter and Paul, the denial of the genocide in Srebrenica “has become a kind of nationalist myth based in one of our religious communities.”

As one of just two panelists from the local Christian community, and a member of the Srebrenica Memorial Center’s new Board for Inter-Religious Dialogue, Ninić advocated “investigating and reinvesting the positive capacity of [religious memory]” by reminding Christians, Muslims, and Jews that their religious texts share critical overlap.

On one point of religious difference, however, a comment by Rosensaft sent a brief burst of levity through an otherwise somber atmosphere.

“There is one thing that you and we share,” Rosensaft said, speaking directly to Bosnian Muslim leaders. “We are not Christians. We do not have an ideology predicated on forgiveness… Our ideology requires action.”