The ICTY was tasked with prosecuting the enormous number of human rights violations that were committed in Bosnia during the war. Although it had a number of successes and was generally well-viewed by the public, the Tribunal faced setbacks and many cases of wartime sexual violence have most likely remained unpunished. As the Tribunal essentially had an expiration date from the start, local jurisdictions – such as the Court of BiH – have played a crucial role in completing its work and building on the precedents it set.

The establishment of the ICTY

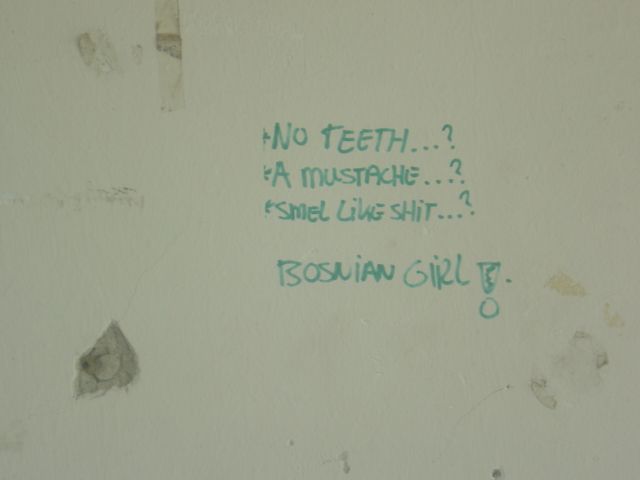

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), which was particularly prevalent during the war in the Former Yugoslavia, is set apart from sexual crimes outside of war zones by the fact that it is oftentimes used systematically as a weapon of war by belligerent parties in order to secure military objectives. Thus, it is not uncommon for wartime sexual violence to be committed as part of an “ethnic cleansing” or genocidal campaign. For example, CRSV can be committed with the intention of terrorizing a population to the point that they never wish to return to the land they were expelled from.

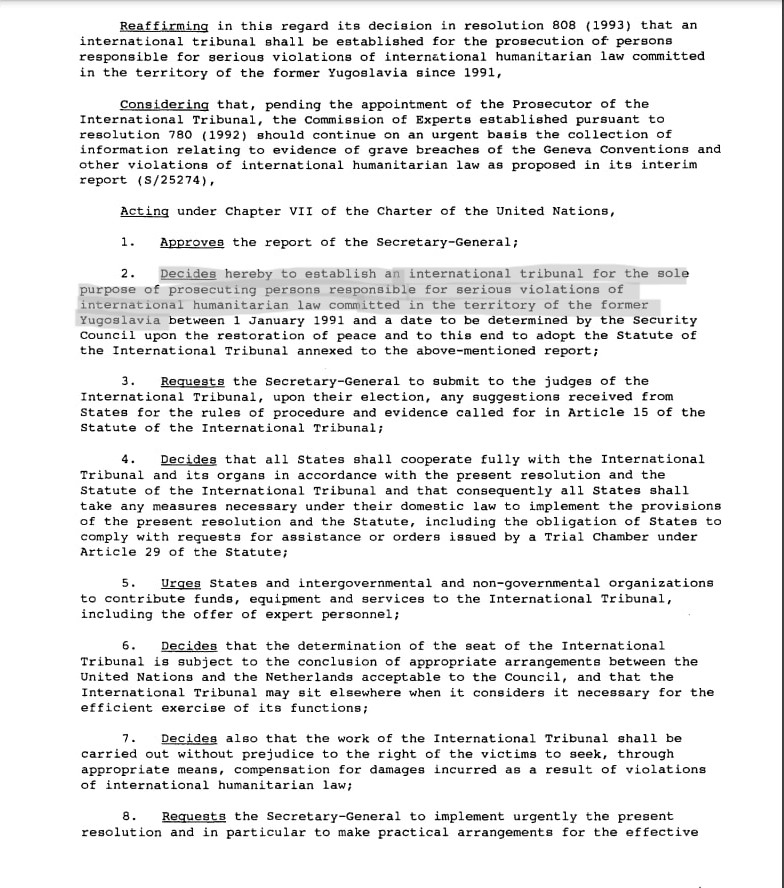

In response to the vast violations of humanitarian law that were being committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the surrounding region, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 827 (1993) set up the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (Bridget Quitter, 2013. This Tribunal, alongside the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), was the first international criminal court since the Nuremberg and Far East trials, and shone a light on the atrocities that took place in the Former Yugoslavia – where tens of thousands of women, men and children were victims of sexual violence, opening up a space for survivors to testify and help bring perpetrators to justice.

Article 4 of the ICTY Statute allowed the court to prosecute genocide, and – under its definition of this crime – established that genocide can take place through “causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group” (Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia). While not explicitly stated, rape and other forms of sexual violence can fall into this category, and thus the Statute paved the way for sexual violence to be tried not just as a weapon of war, but one of genocide as well. Likewise, Article 5 of the Statute gave the Tribunal the power to try those who commit enslavement, torture, and rape in armed conflict, under the umbrella of “crimes against humanity.” This facilitated both explicitly (by mentioning rape as a crime) and implicitly (considering that sexual slavery and sexual torture can fall into the categories of “enslavement” and “torture”) the prosecution of sexual violence in conflict. However, as the ICTY did not establish “sexual slavery” as a crime against humanity, and thus lacked the ability to directly try it as such ( as opposed to prosecuting this form of sexual violence under the “broader crime of enslavement as a crime against humanity”), it was not until the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) was set up that sexual slavery was recognized as a crime against humanity by a Statute (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010).

As of August 2016, 78 people, or 46% of the 161 accused of war crimes by the ICTY, were indicted with charges of sexual violence, including rape, while 32 of those indicted with such charges were convicted (ICTY, “In Numbers”). The MICT was set up to perform functions previously fulfilled by the ICTY after it closed in 2017 (IRMCT, “About”). In the period leading up to its closing, the ICTY also transferred cases to local jurisdictions, such as the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Court of BiH).

The effectiveness of the ICTY in trying CRSV

The ICTY was successful in many ways. It paved the way for reconciliation through the establishment of a body that would at least attempt to ensure war crimes were not left unpunished. One way the Tribunal’s success is made apparent is through the public’s positive opinion and trust in the court. According to a 2021 article published by the International Criminal Justice Review, which surveyed victims of human rights violations in BiH who testified before the ICTY or the Court of BiH, respondents were more likely to see the ICTY as fair when compared to the Court of BiH (Ivković et al., 2021). However, this does not mean the public had no trust in the Court of BiH. While the study reported higher trust in the ICTY than the Court of BiH, a 2007 survey found that Bosnian victims still saw the Court of BiH as the only “fair” domestic court (Ivković and Hagan, 2016).

However, the ICTY faced setbacks which affected its ability to fight impunity and ensure perpetrators of CRSV were brought to justice. A report by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations states that the ICTY and other tribunals established in post-war settings – which are meant to be temporary and thus have an expiration date – are not capable of dealing with all instances of crimes that theoretically fall under their jurisdiction (due to the sheer number of crimes that occurred) (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010). Furthermore, as it is difficult to gather evidence that would prove someone’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt, prosecutors will typically not press charges for cases they are not entirely certain will hold up in court, even if some evidence exists that the accused is guilty of those crimes. For instance, in 2009, Amnesty International criticised the ICTY’s conviction of Milan and Sredoje Lukić, for its failing to take into account allegations and “credible evidence” that the brothers were responsible for the rape of victims near Višegrad (Amnesty International, 2010).

Another obstacle faced by such tribunals is that prosecutors often find it difficult to convince victims and witnesses to help with the investigation, since those who suffered from or were present during instances of sexual violence often do not want to speak up due to trauma, shame or fear of retaliation. Nevertheless, the ICTY did set monumental precedents for witness and victim protection standards. Rule 96 of the ICTY’s Rules of Procedure and Evidence addressed the trauma that survivors of CRSV may experience in court and established that it is not necessary for a victim of sexual violence to corroborate their testimony, and that their sexual history cannot be admitted as evidence by the defence (ICTY, “Innovative Procedures”). It also allowed for witnesses, especially survivors of CRSV, to be protected by them to sit behind screens or even in an entirely different room while testifying (to preserve their anonymity and ensure that they do not have to see their aggressor) (ICTY, “Innovative Procedures”). Nonetheless, many instances of CRSV in Bosnia most likely remained unpunished, allowing as “sexual violence in armed conflicts, including grave sexual crimes amounting to have atrocity crimes, is a much more widespread war crime than is reflected in these judgments” (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010).

The necessary role of local jurisdictions

According to the ICTY’s website, as a part of its Completion Strategy, the Tribunal transferred many cases to local courts, such as the Court BiH, and the majority of the cases transferred included sexual violence charges (ICTY, “Landmark Cases”). Between 2005 and 2013, the Court of BiH, the Federation of BiH and the Republika Srpska, passed convictions for 76 war crimes cases involving sexual violence, which was more than the 68 CRSV charges the ICTY had issued by that point (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014). An increased prioritisation of CRSV cases by Bosnian courts is apparent when one takes into account that between 2011 and 2013 around one in four war crimes cases in these courts involved sexual violence charges, a number which rose to one in three in the period of 2014-2016 (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017).

It is not necessarily that either the ICTY or the Court of BiH was more effective or essential in solving cases than the other. Rather, the two institutions complemented one another, offering different statutes and jurisdictions. The ICTY was not set up to deal with civil suits, or “ordinary” crimes under international or national law (it was, rather, designed to prosecute “grave international crimes” and “consequently their judgements dealing with sexual violence usually concern only grave instances of sexual violence” (UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010). Thus, the assigning of certain cases to the Court of BiH could, in many ways, have overcome this barrier, as this body operates under the country’s domestic law and is capable of trying CRSV cases that do not amount to “grave international crimes.” Given that it is staffed by Bosnian nationals, the Court of BiH has also had the advantage of being able to provide what the Tribunal lacked: an environment where staff understood the culture, social norms, mentality and language of the survivors.

Meanwhile, administrative and judicial support from the international community was a necessary measure during and after the war. It is likely that without internationally established precedents and the oversight of the UN, local jurisdictions such as the Court of BiH would never have been trusted by the local population. It is also plausible that, without an UN-sponsored tribunal, there would have been a greater degree of impunity for war crimes in general, considering that many people involved in the conflict later took on high-level social and political positions in the region.

However, both the ICTY and the Court of BiH have faced a common setback in their attempt to ensure justice is served: the passage of time. Victims of CRSV, potential witnesses, and perpetrators are passing away, setting the stage for certain cases of wartime sexual violence to never come to light or be prosecuted. To combat this issue, a practice was introduced by the Court of BiH in which evidence presented at the ICTY is kept as records, so that certain facts do not have to be substantiated and proven again in the Court of BiH trials, thus cutting down the length of procedures (Diane F. Orentlicher, 2017).

Despite their achievements, local jurisdictions have failed to acknowledge instances of CRSV as what they are, instead labeling them as “regular crimes.” This failure to recognise that certain sexual crimes took place within the broader context of ongoing armed conflict is problematic for three reasons, according to the Organisation for Security and Co-operation (OSCE). First, it denies “survivors an acknowledgement of the specific trauma associated with such crimes” (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017). It also means that victims of wartime sexual violence cannot benefit from the following precedent set by the ICTY: that claims of ‘consent’ cannot be used by the defence in cases of CRSV. Finally, by categorizing CRSV cases as “regular crimes”, limitations on these crimes are imposed, whereas such limitations cannot be applied to war crimes.