Chris Much Bermudez explores two examples of forensic and imaginative war photography, as well as the problems each encounters.

“The Forensic Turn” and “Media and Myth: Mass Media and the Vietnam War” exhibitions, curated by Paul Lowe, Monica Alcazar-Duarte and Ziyah Gafić, explore different angles on war journalism and the stories told by depictions of conflict. On 30 June, as part of the 2015 WARM Festival, the Post-Conflict Research Center’s (PCRC) Velma Šarić joined the curators for a tour of both exhibitions and a panel discussion on contemporary depictions of conflict and the role that art plays in reconciling a violent past.

This article will first explore the content and message behind “Media and Myth”, which was briefly touched upon during the panel discussion, but mainly expanded on by Alcazar-Duarte during her tour of the exhibition, before covering the panelists’ views on “The Forensic Turn” and its exploration of the role of art in remembering conflict.

Alcazar-Duarte’s “Media and Myth” examines how aspects of the Vietnam War have become ingrained in popular culture. One piece visualizes the ‘iconization’ of the AK-47 by laying out hundreds of thumbnails of the weapon from a Google Image search. Why is the AK-47 iconic? First of all, because it symbolizes the Vietnam army’s resistance to the better equipped US Army. But mainly, according to Duarte, because of the influence of popular culture. The AK-47 is a classic example of the glorification of weaponry and the seamless integration of this phenomenon into the media and modern society.

Another section of the exhibit is dedicated to Stanley Kubrick’s film Full Metal Jacket and its depiction of Vietnam. This section explores how Kubrick’s attention to detail in set design allowed him to make parts of London look like Vietnam. For example, Kubrick used explosives and a wrecking ball to turn the disused Beckton Gas Works in London into something resembling a war-torn Vietnam.

When speaking about this work, Alcazar-Duarte placed a particular focus on Kubrick’s “perforating mythology”. In other words, how the actual production of Full Metal Jacket explored the myth that was established about the war and consequently spread by the media. Kubrick showed how easy it was to transform London into Vietnam, simply with the use of explosives and careful placement of palm trees. He transformed one thing into another, artistically recreating a conflict.

Thus, the exhibition aims to re-contextualize Kubrick’s work, underlining the power that art and the media have in telling a story, showing how easy it is to mythologize a war and obscure particular narratives. In doing so, it also highlights how we should always be wary of information received from mass the media. These were the kinds of issues that inspired Alcazar-Duarte and the artists behind the exhibition to investigate the intersection between media, journalism, art and conflict. Alcazar-Duarte added that because much of the work was unable to be explained by captions alone, the artists crafted essays to further explain parts of the exhibition and the motives behind each piece. These served to confirm the idea that there is a lot more to be said about the artworks, but also war, than media often allows.

At the same panel discussion, Paul Lowe introduced his work “The Forensic Turn” with a number of probing starting questions: “How should you photograph the un-photographable?” and “how do you represent the past?” War photography often utilizes graphic imagery that incurs many ethical implications. For example, victims of violence or torture may not want a photograph of an injured, mutilated or deceased relative or themselves to be published because it may reawaken traumas of the past. Furthermore, being repeatedly exposed to explicit imagery may actually desensitize the audience to the conflict, dampening their emotional response and running the risk of them no longer internalizing the gravity of the scene being portrayed. Such a phenomena is of particular concern given that pictures of traumatized people and war-struck towns or cities are becoming commonplace in modern media coverage.

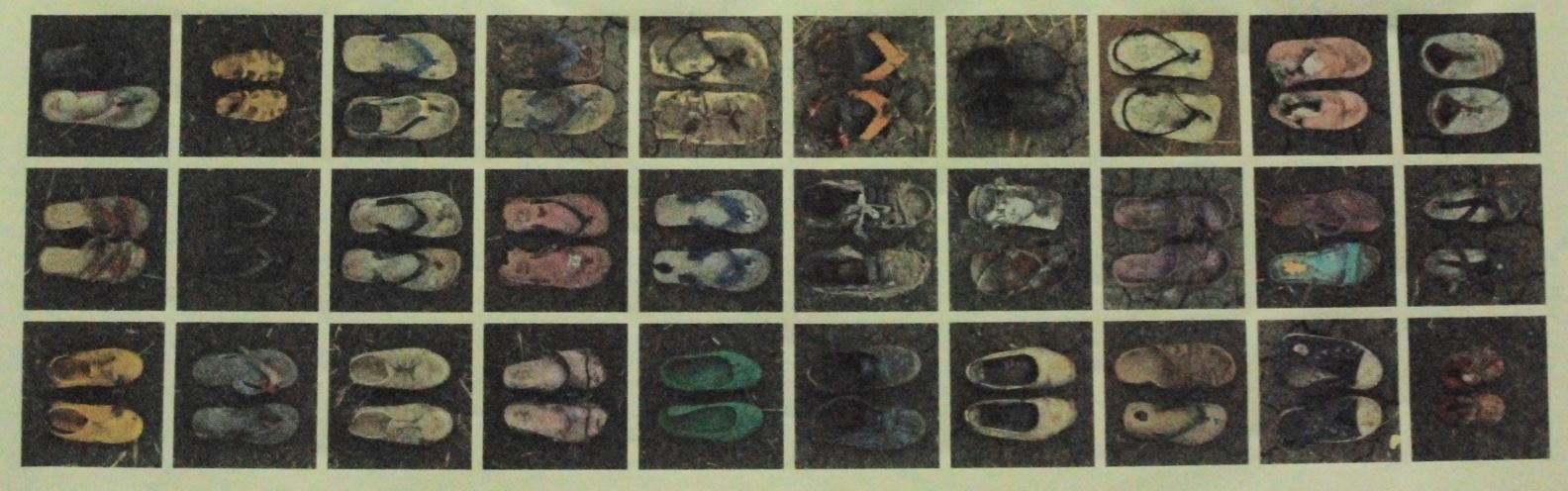

In response, Lowe’s exhibition aims to portray conflict without the explicit imagery to which we are becoming accustomed. Instead, it aims to portray conflict through the presence of absence. The exhibition focuses on artistically showing the audience the forensic element of conflict. One of the pieces, for example, lines up a multitude of pictures of shoes and sandals of missing persons, while another large print eerily portrays the empty bedroom of a missing person.

As Lowe explained, the forensic turn in photography aims to avoid victimization and ethical issues by focusing on “giving the banal a story”. By focusing on ordinary objects instead of people, the audience is invited to think about the conflict and the people affected by it, without having to see the kinds of suffering, destruction and gore of more graphic war photography. The forensic turn is a type of imaginative photography – it portrays what remains of a conflict in order to stimulate the audience to engage with what is missing.

After showing how imaginative war photography was born in the twentieth century and how it was developed by photographers such as Roger Fenton, the panel discussion turned to the problems that this kind of photojournalism encounters. Ziyah Gafić, who photographed parts of “The Forensic Turn”, stressed that though forensic and imaginative photography are seen as more independent and less of a ‘propaganda tool’ than other types of photography, they struggle to remain attention-grabbing and publishable. The mainstream media prefer graphic (i.e. explicit) war photography, because it paints a sensationalist, crude and violent picture of conflict that sells, even though the same images only give a single perspective on the conflict.

Forensic war photography frees itself of just telling that one story, but faces several problems. Firstly, it is less demanded by the media, or, in other words, those that employ photographers. Gafić bluntly added that photography like that contained in “The Forensic Turn” is often deemed to be ‘boring’, exactly because it is not as sensational as other kinds of photography, thus making it even less desirable to those looking for war photography. Secondly, forensic photography fails to fully escape the ethical problems that plague more graphically explicit photography. For example, Gafić did not consider how relatives would feel about him publishing images connected to a deceased or disappeared loved one when photographing the belongings of victims from the Yugoslav Wars. However, he found that the same experience also highlighted a positive ethical element to forensic photography. He explained, “once these [forensic] objects served their purpose, the forensic anthropologists lose interest, and the families do not claim them. And, in a way, photography preserves the objects’ value. Though they have lost their forensic or anthropological purpose, they still have historical or personal value.”

Velma Šarić, Executive Director of PCRC, then added to the debate through stressing the importance of war photography in post-conflict scenarios. She noted that photojournalism is an excellent way of sharing information in public spaces, emphasizing that art and media are crucial in proliferating that information. Šarić discussed how PCRC uses the power of photography, permanent art installations and documentaries to visually present Bosnia-Herzegovina’s recent war-torn history to the current and future generations.

She also explained how photography, along with other forms of media, is capable of generating change and moral courage in times of adversity and rebuilding. Šarić explained that this was the motivation for PCRC and PROOF’s exhibition “My Body: A War Zone”, which opened on Wednesday 1 June in front of the BBI Centar, Sarajevo, adding how it is crucial to share stories, information and photographs about genocide and other atrocities in order to get closer to the truth about the past. In essence, only by understanding the past can we prevent similar actions from occurring in the future.

The floor was then opened to questions, with the ensuing discussion focusing on whether the story told by a picture can ever share what happened within the actual conflict, in addition to whether reconstructing atrocities is a manipulation of the audience and of the facts. Lowe commented that photojournalism theatrically “plays around” with the conventions of truth. Photography can be understood as a form of testimony – not a manipulation as such, but rather a reconstruction of events from the perspective of the photographer.

Alcazar-Duarte then closed the panel discussion by highlighting how projects such as “The Forensic Turn” and “Media and Myth: Mass Media and the Vietnam War” are examples of how photography is constantly trying to reinvent itself. There is no doubt that photojournalism is going through a scary, but exhilarating phase due to the ever-growing influence of social media and the Internet, and is becoming increasingly ethnically and artistically complex. However, discussions such as these both highlight how the field is responding to these challenges in ever more creative ways and remind us that the importance of good photojournalism is a matter of both artistic and social concern.

This article was published in collaboration with Warscapes. The WARM Festival took place in Sarajevo from Sunday 28 June to Saturday 4 July 2015. Run in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center, the WARM Festival in Sarajevo brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.