Monica Alcazar-Duarte’s latest project aims to transform the general public’s perception of her home country of Mexico. David Schafer and Zuzana Pavelkova speak with her to find out more.

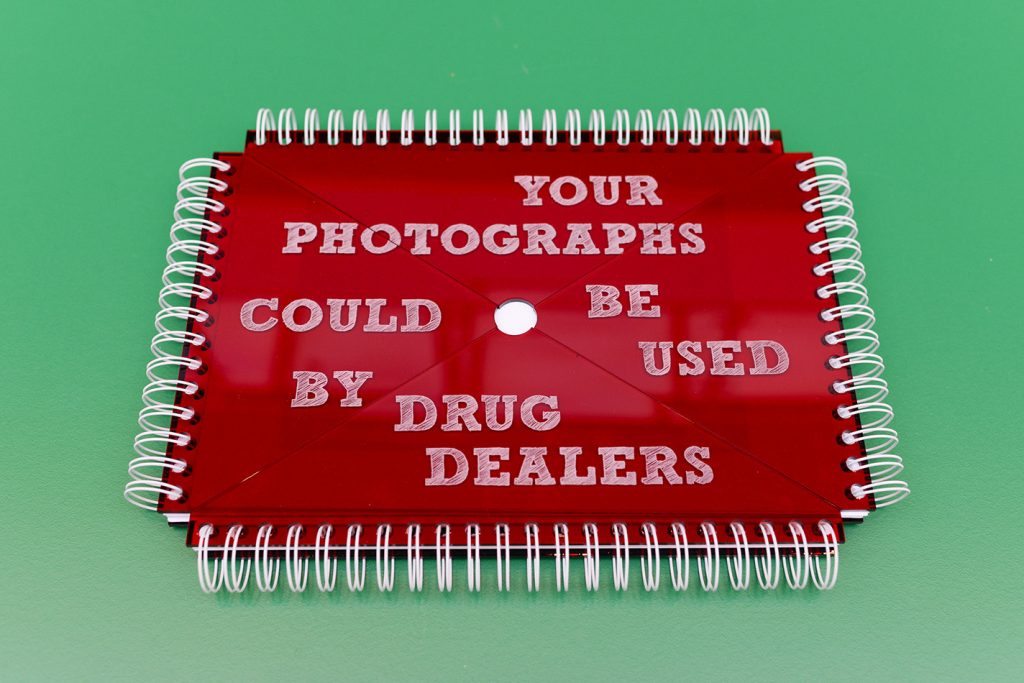

Monica Alcazar-Duarte’s eyes light up as she begins to discuss her most recent photography project, “Your Photographs Could Be Used By Drug Dealers.” She finds herself in Sarajevo after being invited by the organizers of the WARM festival to participate in several panels on media and myths, as well as contemporary photography and photojournalism. Speaking quickly, her remarks on the new project are interspersed with tangents and asides on the abstractness of art and on her desire to inspire interaction amongst her audience.

Alcazar-Duarte’s work was born from the fatigue she felt at constantly seeing her home country of Mexico represented in foreign media as a place of widespread violence. Determined to change what she perceived as a one-sided view, and passionate about transforming the public’s perception of her home country, for her latest project she embarked on a journey to document life in two neighboring towns on the Pacific coast of Mexico, Ixtapa and Zihuatanejo, in the state of Guerrero.

The title “Your Photographs Could Be Used By Drug Dealers” is essential in playing on the expectations of audience members, invoking their perceptions of the country shaped by the media.

She began the project with three objectives in mind. First, to positively influence the charged images that audiences have of her country; second, to use familiar formats and mediums of expression – photography and photo books – in an unfamiliar manner; and third, to question the way that we construct knowledge from images.

Alcazar-Duarte stresses that the work is “less about the photographs, [and] more about the experiences” of both the subjects and the audience, explaining that “you know what you see; you know it from what you [yourself] have seen in the past.”

The project itself focuses on the daily lives and activities of the two towns’ residents, featuring images from families swimming in the ocean at dusk, to moviegoers enjoying a film. The normality of these images is designed to stand in stark contrast to the project’s title and its evocation of the country’s ongoing trouble with drug-related violence, purposefully playing with the audience’s expectations and existing perceptions of Mexico.

The everyday nature of the photographs means that they successfully represent a “certain dignity, certain strength [inherent] in daily life.” Indeed, Alcazar-Duarte does not want to hide the fact that locals are concerned with the rising number of security and police personnel in Guerrero tasked with protecting residents from the drug cartels. The people of the region, she notes, are scared by the violence.

Yet, to truly appreciate them, one should not quickly scan the photos and simply move on. A second, or even third, look is required to appreciate their subtleties. Many of the pictures, for instance, either show or at least imply that something significant is happening outside of the frame, engaging the viewer’s imagination.

By using a photo book where each viewer can change the order of the pages and hereby re-create the story, a fixed understanding or single meaning is discouraged, while subjectivity is stressed.

Key to Alcazar-Duarte’s desire to portray the strength of Mexico and its people is the format of her project – a simple photo book. As an artist she is passionate about the fluidity of meaning, and her work seeks to provide a space for audiences to form their own interpretations of the pictures and to engage with each other.

By using a photo book where each viewer can change the order of the pages and hereby re-create the story, a fixed understanding or single meaning is discouraged, while subjectivity is stressed. As Alcazar-Duarte explains, “a person coming after you would see your version of the book. And that connection is exactly what I am interested in.” Indeed, by removing herself from a position of authority, she allows viewers to be the architect of their own experience and hopes to encourage discussion among viewers on the pictures. At times, when she is present at the exhibit, Alcazar-Duarte will also participate in discussions with audience members: “My presence adds another extra layer of information that the people are missing when I’m not there.”

From the work’s title and images, to the exhibit’s format and open forum for discussion, “Your Photographs Could Be Used By Drug Dealers” is an important piece of work for challenging contemporary perceptions of Mexico. At present, Alcazar-Duarte’s major focus is to grow this project and help it to expand throughout Latin America. The wider implications of her work cannot be ignored, and its success in consciousness-raising can serve as a model for future exhibits portraying the numerous sides to the struggles we face in our daily lives.

More importantly, if used in conflict and post-conflict environments, similar approaches also bear the potential of raising awareness and mutual understanding of different perspectives on contentious issues. Mutual acknowledgment by each of the opposing sides is often key to reconciliation processes. As Alcazar-Duarte concludes, this work emphasizes that though “perspectives can be contradictory… it does not need to mean that they oppose each other.”

This article was published in collaboration with Warscapes. The WARM Festival took place in Sarajevo from Sunday 28 June to Saturday 4 July 2015. Run in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center, the WARM Festival in Sarajevo brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.