A new photographic exhibition in Sarajevo documents the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war. It aims to help survivors transform from victims to participants in the struggle for justice.

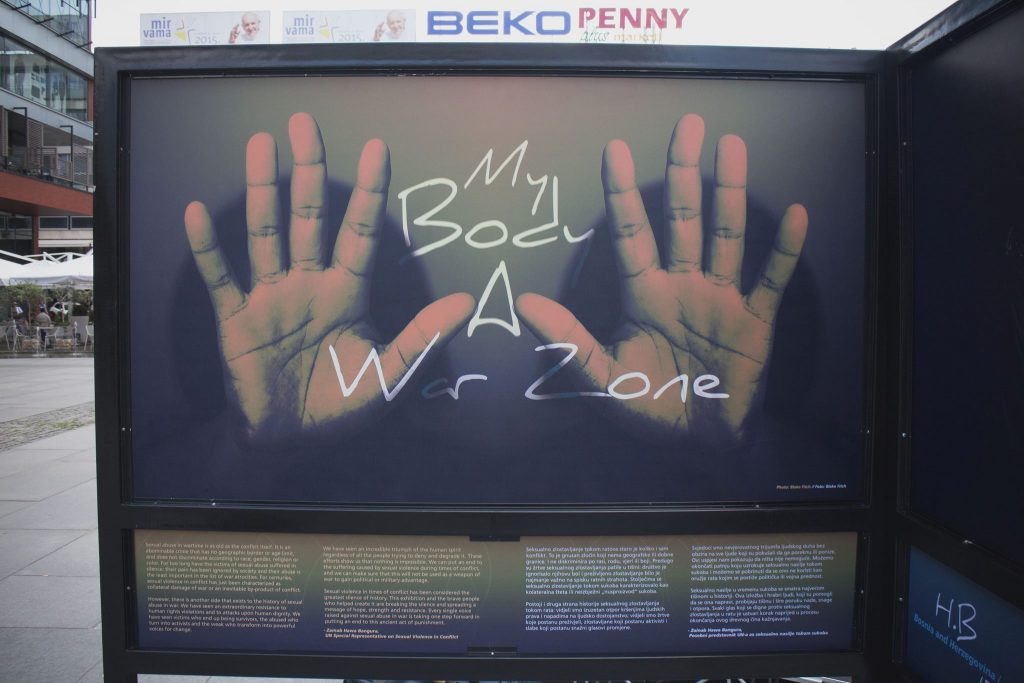

The photographic exhibition My Body: A War Zone was unveiled in the heart of Sarajevo’s city center on 1 July 2015 as a part of the War Art Reporting and Memory (WARM) festival. My Body: A War Zone features the portraits and testimonies of survivors of wartime sexual violence from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Nepal, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The exhibition, developed by PROOF: Media for Social Justice in partnership with the Sarajevo-based Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), aims to bring individual stories of injustice to the broader public in an effort to overcome the silence and stigma associated with crimes of sexual violence. The exhibition is also aimed at replacing the culture of impunity for sexual violence with one of deterrence.

Award-winning photographer, Paul Lowe, opened the exhibition, discussing the importance of making the stories of sexual violence more widely accessible to the general population.

“Displaying these stories in such a visual and public manner is a strong approach to overcoming the stigma associated with such crimes,” Lowe explained.

PCRC and PROOF partnered with photographers Midhat Poturović, Blake Fitch, NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati and Pete Muller to capture the images of survivors from the respective countries. Due to the sensitivity that continues to surround the topic of sexual violence, emphasis was placed on the survivors’ security, well-being and ownership of the final result. Many of the women who shared their stories wished to remain anonymous, which resulted in powerful imagery that, while successfully concealing their identities, captured the cultural nuances of each location and conveyed the gravity and depth of each woman’s struggle.

In his speech at the unveiling ceremony, the British Ambassador to Bosnia-Herzegovina, H.E. Edward Ferguson, stated that “the United Kingdom has been proud to support this exhibition.” While highlighting the UK’s global approach to ending sexual violence in conflict, the Ambassador emphasized that “the UK believes that we must all do more to tackle this problem of wartime rape, to support survivors and to bring criminals to justice.”

Each project photographer used his or her own unique approach to create the intimate portraits of the women who came forward to tell their stories. Bosnian photographer, Midhat Poturović, plays with shadow, light and reflection, to symbolize the plight of Bosnian survivors who are struggling to step out of the dark with their stories. Blake Fitch reveals the intricacies of a woman’s hands, which themselves convey a story of shame and fear, but also of resistance and strength. NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati from Nepal captures dorsal images of each survivor that depict moments of reflection and remembrance. Utilizing the colors of traditional dress and his surroundings, Kenya-based photographer Pete Muller’s photography embodies the vibrancy of Congolese culture, while illustrating the beautiful vulnerability and femininity of each subject.

During the unveiling ceremony, Poturović explained that the Balkans has a history of repeating its past mistakes. “Documenting and preserving these powerful stories for future generations can help us to avoid a recurrence of such atrocities down the road and can serve as a tool to end impunity for perpetrators.”

Also included within the exhibition is background information about each of the countries from which the stories originate, providing the viewers with the context of each conflict. PCRC and PROOF believe that bringing this topic into the public arena can inspire other victims to come forward and tell their stories, which can open the door to improving the current status of victims worldwide.

In an emotional address to the audience, H.B., who survived rape, torture and detainment as a teenager during the Bosnian war, then highlighted the ongoing struggle of women victims of war: “We have been left to our own devices on the margins of society, with no options for psychological, financial or legal support. I urge the Bosnian government to adopt a state law that will regulate our status so that we may have the chance to experience a normal life.”

Sexual violence as a weapon of war

It is estimated that between 20,000 to 50,000 people, predominantly women, were raped during the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia. In the most extreme cases, special camps were established where women were forcibly held and systematically raped over the course of several months. Although women were more likely to fall victim to this sort of institutionalized and systematic discrimination, it is important to note that men were also subjected to sexual violence during the Bosnian war.

Unfortunately, Bosnia is no exception in the widespread recurrence of sexual exploitation during conflict, and there are numerous examples of this throughout history. Sexual violence against German women was exercised by the ‘liberating’ allied forces during and after the end of WWII. In 1971, between 200,000 and 400,000 women were raped during the battle for Bangladeshi independence. Rape was also a common practice during the Peruvian conflict from 1980-2000.

The case of Bosnia differs from other cases, however, in that it resulted in a monumental step forward in defining international humanitarian law. In February 2001, and for the first time in human history, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) recognized rape as a powerful tool of war, used to intimidate, persecute and terrorize the enemy. In the various judicial proceedings that followed, the ICTY enabled the prosecution of sexual violence as a war crime, a crime against humanity and genocide.

Despite such progress in the field of transitional justice, sexual violence continues to be an intrinsic part of war and conflict today, and its consequences have long-lasting and far-reaching impacts that must be continuously addressed.

Breaking the taboo and empowering the victims

It is alarming that twenty years after the end of the war in Bosnia, victims of sexual violence continue to face stigmatization and social exclusion, which often originates within the circles of even their closest relatives. Even more disconcerting is the fact that many of these victims must continue to cross paths with the perpetrators in their everyday lives.

By placing the exhibition in front of the BBI Center, one Sarajevo’s most trafficked areas, PCRC aimed to bring these stories into the public arena in an effort to break with the prevalent practices of victim blaming and silence surrounding rape.

“We need a change of attitude. It is the support of families and communities that can make a key difference in whether survivors of such crimes can regain their dignity and make a positive contribution to their societies,” highlighted Ambassador Ferguson.

Including the general public in the dialogue on post-war justice is an important step in demanding accountability from the perpetrators and breaking the taboos associated with crimes of sexual violence. Most importantly, exhibitions like My Body: A War Zone bear the potential of empowering the victims to speak up and thereby evolve from mere objects of violence to active participants in the struggle for justice.

Beyond the Exhibition

In 2010, PCRC’s Executive Director, Velma Šarić, began working with UNHCR Special Envoy, Angelina Jolie, in an attempt to further catalyze the discussion surrounding survivors’ rights. With the discussions elevated to an international level, the International Protocol on Investigation and Documentation of Sexual Violence in Conflict finally emerged. Partnering with the British Embassy in Sarajevo, PCRC was involved in a range of local activities that brought together representatives of public institutions, civil society organizations, youth, academia and the media to raise awareness on this important matter and to introduce international standards for the documentation and investigation of sexual violence in conflict. PCRC assisted in the organization of the Protocol’s launch in the Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia-Herzegovina and was in charge of bringing it to public audiences across the country. Together with the Protocol, the exhibition was presented in Mostar, Banja Luka, Brčko and Zenica.

Exhibitions like My Body: A War Zone make up only one part of PCRC’s approach towards empowering women and advocating for the rights of survivors of sexual violence. Additional PCRC projects that contribute to these aims include the photographic exhibition Warriors of Peace and the documentary films I Came to Testify and Unprotected.

PCRC believes that incorporating the use of multimedia to address human rights issues can prove highly effective in bringing to light the injustices of contemporary conflict that remain neglected by politicians, misrepresented in the press and often ignored by the public.

Paying testament to the women who came forward to share their experiences with the world, PCRC’s project developer, Tim Bidey, brought the exhibition opening to a close, concluding: “Without your bravery, all that we are talking about and trying to achieve today would not be possible.”