Enrico Dagnino’s photography tells the stories of conflict. Most often, these stories are difficult to convey, difficult to observe, and difficult to understand. An interview with Dagnino gives insight into both his career as a photojournalist and his exhibit, “Untitled”.

Enrico Dagnino’s photography tells the stories of conflict. Most often, these stories are difficult to convey, difficult to observe, and difficult to understand. They are stories of war, of the atrocities committed by humanity against its own kind. Through documenting and processing these narratives, Dagnino also shares stories about himself within the private workings of his studio. An interview with Dagnino gives insight into both his career as a photojournalist and his exhibit, “Untitled”.

By: Laura Feehs & Anna Bianca Roach, Interns at the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC) in Sarajevo

Enrico Dagnino’s current photography exhibit, Untitled, offers a glimpse behind the published photographs and into the humanity of the artist. This solo show featured at the 2016 War Art Reporting and Memory (WARM) Festival in Sarajevo, peers into his lived experience working in the field of war photojournalism, and his attempt to reconcile his professional life with that of his life at home in his studio in Paris, France. Raw, unfiltered, and deeply cynical, Untitled is more about Dagnino himself than about the events he covered, and portrays the intense turmoil he has faced.

Prior to the exhibit’s opening, Dagnino discusses the integration of photography into his life – a pivotal moment that propelled him into a career in war photojournalism. On 29 June, over a morning espresso at the Meeting Point in Sarajevo, he recounts his early struggle with writing and how he never excelled in conversing with people, but he explains that photography gave him the platform to speak out, a voice to be heard. At the age of 18, a friend placed a camera in his hands thus unwittingly transforming Dagnino’s ability to communicate with the world.

The fall of the Berlin Wall marked the beginning of Dagnino’s ongoing journey to document conflict. At the time, the adrenaline he experienced while capturing history enticed him deeper into the field. While relaying memories of his time in the Balkans, he laughs as he recounts his late night navigation through the streets of Sarajevo, where he had to briefly pause as mortars exploded, then continue his sprinting around the blocks. “It wasn’t for a photo, though,” he notes. “We desperately wanted pizza from across town, so we ran through fire to get it!”

In 1991, Dagnino found himself in Vukovar, Croatia during the three-month siege of the city. “Vukovar was the Berlin Wall of my own life,” he solemnly states. “I lost hope. If people are able to do the things I’ve seen, anything is possible. We are capable of anything.” He continues sharing his sense of guilt – of indirect responsibility – that we, humankind, contribute to violence. “We are part of the same humanity,” he says, to suggest that we are all culpable at some level for the barbarism of war.

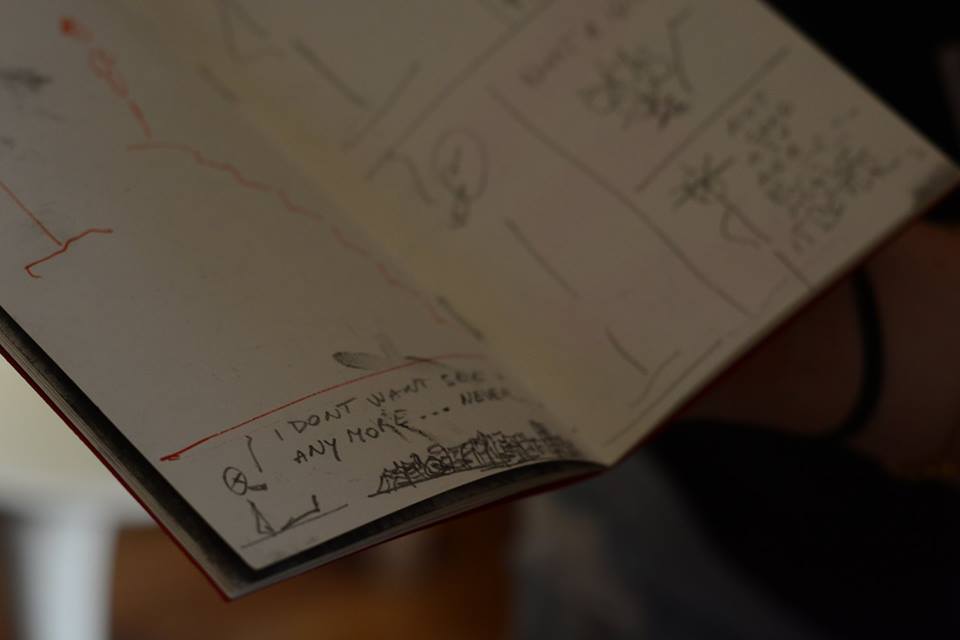

In his attempt to process these realities, Dagnino finds solace in the haven of his home studio where he sketches, writes, and withdraws for a time. The pieces included in his current exhibit help to explain the dichotomy of “living in two different worlds.” Dagnino’s Untitled is particularly striking for the immense sense of vulnerability and intimacy it leaves his audience with.

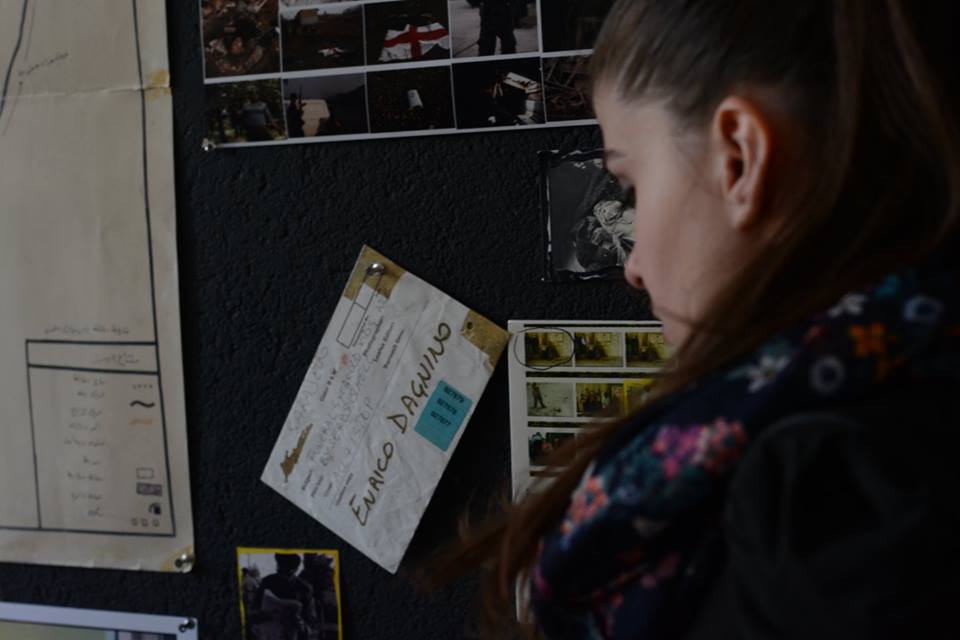

The exhibition, hosted in an apartment in one of Sarajevo’s Austro-Hungarian era buildings, consists of two parts. Half of the space is dedicated to the exhibit proper, where one can see some of his best photographs. The other half – the more personal and more striking part of the exhibition – is a room left in purposeful disarray, with a replica of his desk and a wall decoration filled with his own personal belongings for the audience to rummage through.

The exhibition also leaves the audience with a sense of voyeurism: Dagnino’s journals reveal conversations with his partner and loved ones, deeply personal accounts of his travels, and pages upon pages of raw, visceral anger and sadness. Interestingly, he also notes that “[conflict zones are] the only place I feel good. I feel good with the people. I feel good with myself.”

Interspersed with the existentialism of his thoughts on conflict and personal relations are more light-hearted pieces. In the array of memorabilia, the audience can also find Dagnino’s old press passes, credit cards, and pornography. “This is my desk,” he declares, when asked why he chose this medium for his Untitled exhibition. “I’ve done this once before [in Paris] – but this time, it’s smaller. It’s different.”

Fraught with Dagnino’s harsh perspective on reality and his characteristic mix of cynicism and audaciousness, Untitled has the intense ambiance of a memorial exorcism. It feels like a pyrrhic declaration of freedom – perhaps from the duty to report, perhaps from the psychological effects this duty has had on him, perhaps from the audience itself.

Through his incredibly brave vulnerability to share his inner experience in conjunction with his professional work, Dagnino thrusts the weight of his career onto his audience, shedding the photojournalist’s classic bravado. Whether it is ultimately put up for himself, for his audience, or for a third party is unclear: nonetheless, it deconstructs reporters’ often-romanticized experience of war to demonstrate that “beyond the violence, there is a story. A human story.”

—

The 3rd annual War Art Reporting and Memory (WARM) Festival took place in Sarajevo from Sunday 26 June to Saturday 2 July 2016. Organized by the WARM Foundation in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), the Festival brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.