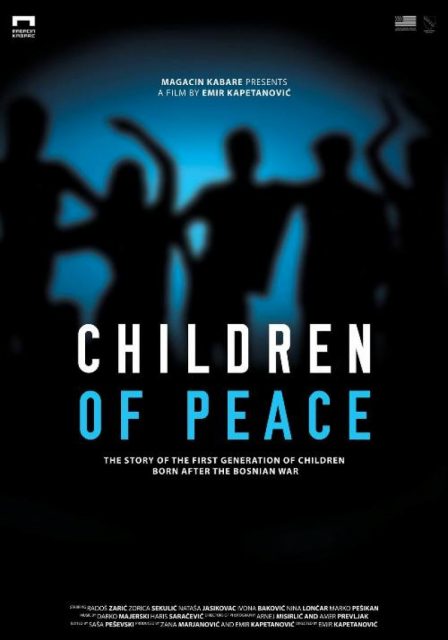

Balkan Diskurs correspondent Louis Monroy Santander talked to Emir Kapetanović, director of “Djeca Mira” (Children of Peace) – a documentary that takes a look at the post-Dayton generation in Bosnia, their concerns, their realities and perhaps more importantly their dreams.

Balkan Diskurs correspondent Louis Monroy Santander talked to Emir Kapetanović, director of “Djeca Mira” (Children of Peace) – a documentary that takes a look at the post-Dayton generation in Bosnia, their concerns, their realities and perhaps more importantly their dreams.

Louis Monroy Santander (LMS): How did the idea for Children of Peace come about?

Emir Kapetanović (EK): I started doing documentaries at the Academy of Performing Arts in Sarajevo and the focus was on the National Anthem. We approached citizens in three major cities, asking them to give us a voice and lyrics to our National Anthem. After this project, I started organizing the Magacin Kabare, a space where we could talk and deal with complex social issues via a satirical approach that allowed us to open dialogues with our audience. This project led to the creation of the Mali Magacin Kabare, a space for young people where we approached social activism through art. We just wanted to have a dialogue on the things that were most important to kids, to hear their views and to support them in presenting their work. We also taught them how to present to different audiences and create films.

During the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Peace Accords, we came up with the idea of ‘resemblance,’ of those things that are common to all people. What we understood was that we needed to avoid putting people into the usual ethnic categories and to instead find just one thing that was common for all of us. We came to this realization that we have different words for war in our local languages, but we have the same word for peace. This led to developing an understanding that there is no one better to talk about peace with than those who were born during times of peace, and this is how the idea for Djeca Mira started.

Kids are used to talking about the past, they learn about it from their relatives and often repeat what they are told. This particular challenge allowed me to develop the idea for Children of Peace: to visit six cities and ask kids about their views on their cities, the country and the future without necessarily talking about the past. You can see what their thoughts are and what are those of their parents when they express views about the past. We wanted to work on the future, on their situation today and to create an artistic performance via multimedia in order to spread this idea. We all hear the phrase “the children are our future” but then we never really ask kids about how they see their future. So we developed the methodology for this, to spread this idea.

LMS: What sort of challenges did you encounter when making Djeca Mira?

EK: Certain politicians in BiH do not want these types of projects around. The reality of the situation is that they do not want kids from different backgrounds to get together. For the older generations, it is possible to meet as we have an understanding of a united past. Children who didn’t grow up with that shared narrative, however, are more susceptible to divisive politics. In the case of the film, we made the children choose for themselves who would be the representatives of each of the six Bosnian towns that we would be filming in, and without asking anything about ethnicities or religious affiliations. Yet, when discussing the film and its methodology people constantly asked why there was no mention of the children’s ethnic identity or information about their ethno-religious background. For me, the movie is about them and their views, so why must people ask about ethnic backgrounds?

These types of projects can be successful simply by gathering two kids from one small town to meet with others across boundaries. It will be harder to divide them once they develop relationships with each other. In BiH, we don’t know enough about one another. When you know someone it becomes much harder to maintain hateful stereotypes and viewpoints about them. The methodology for Children of Peace allowed for these kids to come together. What we did was get every kid to write down what their assumptions were about each city and we used them to compare and contrast with their field visit findings. Through this process, it was easy to visualize how the media manipulates us and how little we really know about the different towns in BiH. I think we need to keep exploring, to maintain these cultural excursions, to go and visit different places and form our own opinions. NGOs need to work more and more on this, on making art that highlights different views and understandings of social and political issues.

LMS: Do you see your work as a form of political resistance?

EK: I think this form of art is oppositional in a way. We are doing what politicians should be doing, finding ways to live in harmony and contribute to the process of building a country together. Don’t get me wrong, we need politics, we should have politicians and political parties. They should, however, exist in a system where we are not simply just voters but active creators of a program. In my work as a producer it helps to have a political atmosphere that allows me to create and not worry about things outside of my reach, but in Bosnia what we need is for politics to work for us. Then again, through creative work you can have a strong cultural impact. I cannot work without combining politics and art. Culture and sports can make this country more united and work a whole lot better.

LMS: In your opinion, what is your contribution to the peacebuilding process in Bosnia?

EK: I think we are simply connecting different spots. This is what peacebuilding is about. You cannot build peace simply with your own bricks. All people, from different backgrounds and different viewpoints bring their own bricks and build together. What we need to do is help the people to work together, without necessarily rejecting or going against the beliefs that construct their identity.

LMS: What are your views on the process of dealing with the past, remembrance, and memorialization?

EK: I think that, as adults, we need to talk about the past, particularly to prevent future mistakes and learn from what happened. But with kids, they live in a new era; they do not need to be a constant part of that painful past. We need to be able to talk about the past without manipulating the kids. It’s not right, they had nothing to do with that, they were not part of that war and it’s not their responsibility. Perhaps we can get them to deal with the past by studying and looking at things from a completely different perspective.

In relation to the memorials about the past, I am more of a future-oriented person. Yet, if I tried to work on dealing with the past, I would make a film where we could combine different pasts. I would make a film that looks at the issues of war from the perspectives of three directors from different areas of Bosnia, combining their viewpoints to expose the nonsense behind the conflict. It is important to talk about Srebrenica and Auschwitz, but you need to see it as a tragedy of civilization. We should not dwell on political points for one side or another, but instead show humans and the evil we are capable of, in order to prevent future genocides.

Correspondent’s note:

After spending over an hour with Emir Kapetanović, I found his focus was primarily on his relationship with the youth and his concerns about the ethnic divisions that were put in place both by postwar Bosnian demographics as well as polarizing practices within the Bosnian education system. Despite these concerns, he has hope for the future. He believes that Bosnia’s youth can one day approach historical divisions from a different perspective and can help positively influence and transform Bosnia’s ongoing social reconstruction.