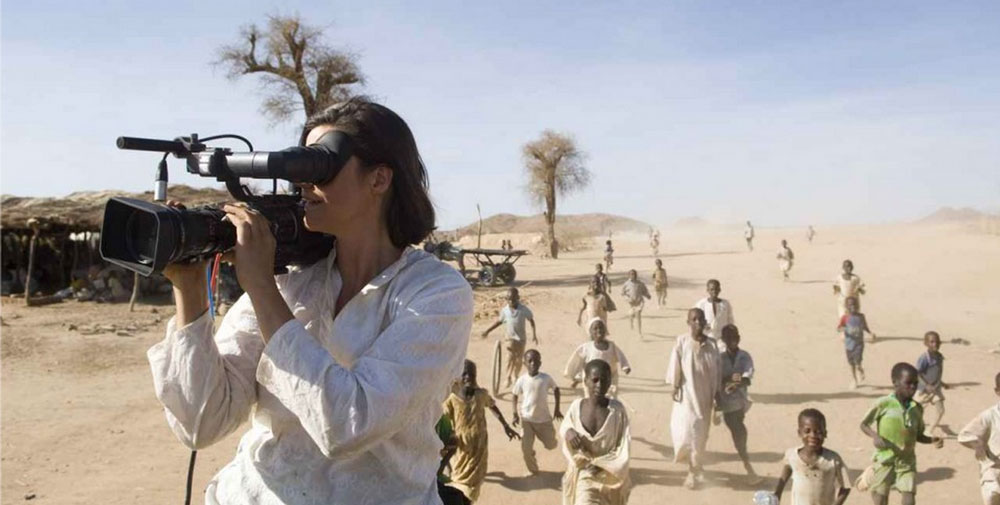

Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson is a highly personal take on her experiences of shooting various documentaries around the world.

Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson is a highly personal take on her experiences of shooting various documentaries around the world. The film takes its audiences on a journey across the feelings, dilemmas, joys, and concerns that accompany the filmmaker from the moment she picks up her camera and starts shooting.

After having had the opportunity to appreciate the intricacies of filming in places like Afghanistan, Bosnia or Guantanamo to the filming of beautiful and intimate family moments in her life, I kept wondering about the sort of critical reflections that go through Kirsten’s mind when shooting in such difficult contexts. It also made me reflect on the role filmmakers play in the processes that occur in sites of social conflict, the sort of ethical decisions that are made during shooting, and the way filmmakers connect with the communities and individuals they shoot.

Thanks to my internship at the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC) in Sarajevo I had the chance to interview Kirsten Johnson and gain an insight into many of these issues. PCRC’s Founder and President Velma Šarić previously worked with Kirsten on the Bosnian portion of PBS’ Women, War & Peace documentary series. Among other topics, we spoke about how to gain the trust of the individuals and communities one works with, the role of film as a source of narrative and memory construction, and the ethical preoccupations that this type of work entails.

Since Cameraperson depicts the ways people being filmed connect with the person filming them, I asked Kirsten about the process of relationship-building that occurs in this type of work and how she was able to gain the trust of the people she was working with. She said:

“There is this idea that filming is relationships, whether you are trying to create relationships or acknowledge their existence. Once the camera is present and images are filmed, they go into the future in ways that you cannot know and they may be very meaningful for the person behind or in front of the camera, or even both. It may be that you are putting evidence of a moment in history, or maybe that you are given a chance to let someone speak who has never had a chance to speak, or simply documenting a person being alive who may not be alive forever. There is no question that I feel a connection in those moments when I film with people and I think that has value for me.”

As a researcher, I was quite intrigued by the process of interaction that occurs between different cultures, between the researcher and the researched, and, in Kirsten’s case, between the filmmaker and the person being filmed. Without a doubt, these interactions are often marked by power relations that affect both research and film products. In light of this concern, my second question was about the cultural negotiation that occurs during the filmmaking process, to which Kirsten stated:

“Cameras are objects of power that can create imbalances as certain people can win and twist narratives and misrepresent. Or sometimes our own unconscious bias or naiveté leads us to terrible mistakes in the representations of others. This is the struggle that we are in and none of us should be so arrogant to imagine that we will ever get it right, but also none of us should be so heuristic to imagine that we are so important.”

Cameraperson shows us a collage of different stories, portraying different social, political and economic issues. As such, it relies on narratives and stories constructed from different viewpoints that can help illustrate the magnitude and complexity of social phenomena. Bearing this in mind, I asked Kirsten about her role in the process of constructing narratives in sites of conflict. Her response:

“Someone just called me a memory worker, which is kind of fantastic. I call myself a filmmaker, that is what I do, I make films, but I love when they call me a memory worker because certainly with this film I am doing work which represents a form of memory which is fragmentary and incomplete. All of our own memories are incomplete and get re-imagined. But there were things that actually happened, and clarity around what those facts are and what happened is important, especially in places that have had wars, so I am all for uncovering facts that have been forgotten, buried and never spoken of. But part of what I want to show in this film is that stories are constructed, history gets constructed by different people and our identities impact the way we choose to construct this story.”

Kirsten further illustrated her point by referring to some footage that was shot in Bosnia-Herzegovina:

“The movie’s scene with the girls playing ping pong in what used to be a wartime rape center in Foča engages directly with the contestation of memory. The construction of this narrative and that place are contested memorial spaces. People came and tried to put a plaque on that building which said that women were systematically raped there. They were driven out of the town and came back to Sarajevo with the plaque in their hands. People using that facility have no idea of what happened there, it was used as a sports center. I tried to speak to this and give evidence of all the different things we do with memory, of spaces where atrocities happen where some have no memorials and some are used as public space without any idea of what happened there. Others have expensive memorials built on them. All of these are factors that show how contested the actual events are and of the powers behind them.”

Finally, one of the most intriguing themes had to do with the methodological risks that can occur when planning and making these types of films, particularly when they rely on people who have experienced trauma, who may be representing one side of a conflict or who are interested in promoting a specific view or narrative of conflict. With this in mind, I asked Kirsten what consideration she has given to the ethics of filmmaking in conflict zones. She said:

“We are trying to understand very complex situations and it may be that we misunderstand, misrepresent or are maybe even fooled at times, but I think if we continue to acknowledge the edges of the film, the relationships around things, we are being ethical. I am intrigued by these moments where you know other things are happening during filming, where someone you thought had one agenda has a completely different agenda and how it plays out during filming. It makes you think about the issues. We need to acknowledge that these issues are part of what humanity is, of the role of survival and how war and trauma affect people. Through this, you can learn how reliable a narrator someone can be of a traumatic event. It leads you to question the reliability of all of our narrations, question our own subconscious bias and realize that all these things shift in different moments in our life. Take my filming in Foča. This area is still a hostile territory and a scary place for those people who testified in The Hague Tribunal. I have always wanted to know what it would take for me to take my footage and show it in Foča, but I cannot do that as I do not live there, the family I filmed has to live there. It is easy for an international to have a conceptual idea about what would be important to show in the film, but a local person has to live with the consequences afterwards.”