People with disabilities are among the most marginalized groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, facing discrimination and stigmatization daily.

The definition of a person with a disability is still not consistent in BiH, although the country adopted the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In Serbia, by law, the term “persons with disabilities” means “persons with congenital or acquired physical, sensory, intellectual or emotional disabilities.” Due to their status, many organizations strive to improve their socialization and motivation for professional development by giving them employment opportunities.

Legal Framework for People with Disabilities in BiH and Serbia

According to the BiH Agency for Statistics, around 270,000 people live with disabilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Laws at various levels regulate their employment and establish funds for vocational rehabilitation and work for those with disabilities.

In Serbia, according to the census from 2011, there are 571,780 people registered with disabilities. The “Law on Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment of Persons with Disabilities” defines vocational rehabilitation as “organizing and implementing programs and activities to train for appropriate employment, recruitment, maintain employment, advancement or change of professional career.” According to the same law, those employed with disabilities can earn 100% of the average salary earned in the previous three months before joining a government-sponsored rehabilitation program. The salary compensation may not be less than the minimum wage in Serbia.

“People with disabilities in the Republic of Serbia represent one of the most vulnerable groups in all areas of social life, which is confirmed by the practice of the Commissioner, i.e., the number of complaints received by the institution due to discrimination based on disability,” said Brankica Janković Commissioner for Equality.

In addition, similarly to the law in BiH, the law in Serbia defines the employment of people with disabilities under both general and special conditions. General conditions mean “employment without adjustment of tasks and/or workplace,” while special conditions are considered “employment with adjustment of tasks and/or workplace.”

According to research published by Istinomjer women with disabilities find it harder to get a job than men, who are often given preferential treatment by employers, particularly if they fall under the category of “war invalids.” They also found that in 2015 in FBiH, women made up 26.6% of the total number of people with disabilities employed in 2015.In Republika Srpska, women only made up 6.2% from 2013 to 2016.

Ana Kotur Erkić, a lawyer and journalist in BiH who also lives with a disability, began working as an activist for people with disabilities seven years ago. However, she says that it has been a lifelong struggle for her. Activism later grew into what she called “human rights advocacy.”

“I was also active as a child – I stood against injustices, I was loud and always questioned ‘why?’ and ‘how?,’ but [seven years ago], for the first time, I seriously got into this as a journalist. Then, I was an editor for a portal on people with disabilities and then a contributor to many media organizations. Being a human rights defender, as a person who goes through constant discrimination, almost from the moment I leave my home, is not easy. I am constantly exposed to criticism because I do not fit societal norms, and I also carry the burden of the community on my back,” says Kotur Erkić.

She points out that discrimination is most noticeable regarding employment since she has still not found a permanent job.

“Since I have experience with more than 80 rejections, [I know that] going through this process is long and difficult, and I can say to survive and endure is certainly even harder. There are moments when it is indescribably difficult for me, when I am desperate and when I feel very bad since it is really unrealistic that I am still told that I am not a good candidate after so many applications. But, on the other hand, constant degradation and humiliation is great motivation for me to keep fighting,”Kotur Erkić says.

She says that while she struggles, she has also had great joint successes with exceptional people, be they in a non-governmental or institutional framework, the academic community, or a shared experience with life on the margins.

“When I recall of where my starting position was, what battles I won – I simply do not have the space to give up. My environment – except those closest to me – my society and the country in which I live are not favorable to people like me,” Kotur Erkić continues.

In her work, she turned to advocacy for those who cannot speak out.

“We have seen that society and the state do very little for all the people who live here, but have we done everything not to be in the position we are in? I know that I am still doing everything and that I am, in many regards, far ahead of what is expected of me. The employment process, as well as other things like education, housing, and access to justice, are not adapted for people with disabilities,” she emphasized.

She points out that laws and bylaws are insufficient to remedy the situation, and inadequate implementation and lack of real sanctions for those who do not want to employ a person with disabilities add to the issue. There are also few vacancies and poor work environments.

All this, emphasizes Kotur Erkić, shows that the labor rights of persons with disabilities are not implemented adequately.

Getting a Job Through the NGO Sector

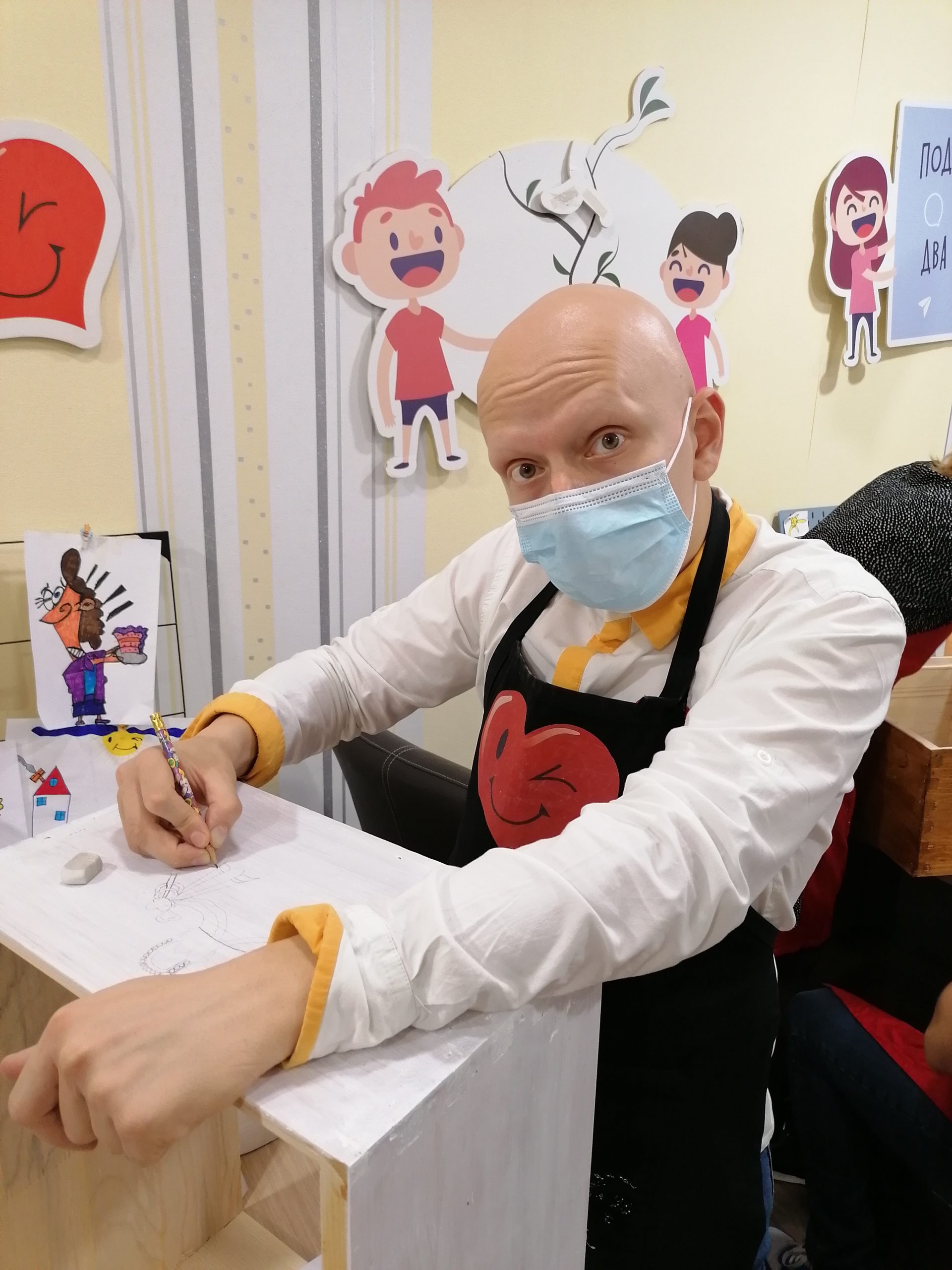

Goran Rojević is the director and founder of the organization “Children’s Heart” from Serbia, which has been helping people with disabilities, their parents, and people who care for them for 20 years. According to Rojević, the organization now runs the “Sounds of the Heart” café, which, according to them, is the only one in the region where all employees are people with mental disabilities.

“The crown jewel of our work is helping them become as independent as possible and enabling them to live well and be professionally useful members of society. The café, together with the work center, aimed not to differ much from life in Belgrade, where restaurants and cafes function best. We have determined professions that could be performed well,” says Rojević.

He says that the employees live with them and go through the “School of Life” and “School of Life Skills” programs and additional training for bartenders and waiters.

“We place them in real-life situations from which they learn at a concrete level. When you train someone to be a waiter or a bartender, you put him in a challenging situation. When he says, ‘but I don’t know this,” then you teach him. Social mentors our employees with all of this,” describes Rojević.

He emphasizes that they are exceptional in all fields of work and that a good atmosphere is important for their productivity. Rojević adds that they help other colleagues in their activities when they finish one job. Working in a café has a positive effect on them.

“Together, we developed various social services and helped spread awareness so that people no longer think so much about their suffering in the past, but instead about how they can help other people. Society is more open than it was 20 years ago. Then, people were more focused on themselves and their problems. Now, [people with disabilities] are present in many schools, kindergartens, and educational institutions, where they were not 20 years ago,” says Rojević.

Rojević states that people with mental disorders tend to age out of the workforce more quickly, so it is better to hire them at an early age so that they can work longer and be active members of the community.

“When they are 18, we look for activities where they can spend a lot of physical energy. We have continued this with the “Center for Training and Employment of Persons with Disabilities. ”Through that, we recommend them to certain companies from the local community, and those companies employ them. They always have a kind of partnership with us, and in case of problems, we act as mediators.”

In addition to cafes, the organization also has a “Personal Companion of the Child” service, which operates at the local level through the government. Personal assistants are trained and cooperate with schools and institutions attended by children with disabilities. Rojević also says often, employees manage to become independent.

One of the employees, Marko, regularly makes espresso and waits for the guests’ reaction when they taste his coffee. Nemanja decorates beehives with his drawings for the agricultural farm in Vinča, where people with disabilities will work.

“I am drawing the coat of arms of Obrenović on the baskets here. I try to make it look perfect. I get tasks from my work instructors,” says Nemanja (27), one of the employees whose mentor says he has a photographic memory.

Nemanja says he would love to meet foreign actors in person and insists he would not be shy.

“I try to make everything nice and invite celebrities to visit here. I wanted the actors from the “Game of Fate” series to come here,” Nemanja says.

“I get the assignment to be in a café sometimes, and sometimes in a workshop to help. I make coffee, cocktails, and lemonades. Sometimes I cook lunch in the kitchen. I know how to make macaroni, I know pasta, and how to cook soup. I know how to bake sausages, and it is easy for me to prepare mashed potatoes,” says Nemanja as he describes his working day.

Not only can Nemanja cook, but he can also draw. It is not difficult for the versatile Nemanja to draw the “Children’s Heart coat of arms.”

When asked what he dislikes, he pauses.

“People joking around with me. And unsalted food.”

In general, he says, “I love everything.”

When asked how long he has been here, Nemanja knew the exact date immediately – the 24th of December, 2018. He tried to look for a job elsewhere, but it was difficult for him. He says that, eventually, he would like to do some work related to drawing.

“I would like that; I was thinking of doing something in a printing house, printing T-shirts and mugs. One day, not now. I still have to learn from work instructors. I can’t learn anything without them.”

Another employee, Anđela (22), has been at the center for three years, and she helps grow lavender there.

“I listen to what the work instructors tell me. It’s not a problem for me,” she says.

In addition to growing lavender, she also likes to work as a waitress and in the kitchen. She says she wouldn’t change a thing about her experience.

“I would stay here, and I would not change anything. Unless one day I get bored. Maybe I would do something with a computer, write and draw, something like that. I also like to draw at home,” says Anđela.

Parents are the Biggest Support for Those with Disabilities

In Goražde, a small town in BiH, there is the “Association of Persons with Cerebral Palsy and Dystrophy.” For many in the small town, this association represents a positive side of the society in which they live. One of their members, Alen Hedo, shares his life story with us.

“Since I was seven months old, I have had cerebral palsy. My family tried their hardest to make society include me. When it came time to enroll in school, the biggest problem was, to some extent, systematic barriers. Some people thought it might be better for me to be at home than to go to school because they thought it was too difficult for me,” says Alen.

He also said that navigating the stairs to reach the upper floors of his school was also a big challenge.

But Alen overcame it all with the help of his family. He says that he would not be what he is today without them. He grew up with two sisters, and he received full support from both them and his parents.

“After enrolling in primary school, my mother firmly decided that she wanted me to go to school. We didn’t have a car at the time. Every day, she carried me for five kilometers in both directions, including a backpack and all the equipment I needed. After a couple of years, we finally resolved the problem. A van was provided to drive the teachers, and they started picking me up along the way. After that, I enrolled in high school, and my father drove me,” continues Alen. He explains that his father could not get a job because he drove him to school every day, including university and sports activities.

He says he felt at home with the association and found many activities he could participate in.

“Society, ordinary people, my friends – they have never made me feel like I am less of a person. It indicated that I actually need to fight like any other person to achieve success in every aspect of life. The same is true for education. My main motivation is my family. I also wanted to show others that everything is possible, and if you decide that your place is among those with Master’s degrees, then you can achieve that,” says Alen, who has his Master’s degree and plans to enroll in a doctorate program.

After graduating, he was given the opportunity to volunteer at the local MOI. There, he says, he had everything he needed as a person with a disability.

“There were no stairs, and the workplace was adjusted. I really enjoyed every day while working there. I was especially happy to work with citizens who had the opportunity to meet people with disabilities through my engagement. I worked on issuing personal documents, and I mostly met people there who were physically capable. They had the opportunity to see that people with disabilities deserve a place in society.”

He was subsequently employed in the high school, but the COVID-19 pandemic paused his two-year employment. Since then, he has struggled to find employment again.

“It is very difficult for people with disabilities to get a job. The system is somewhat to blame, and, on the other hand, the private sector does not invest enough in knowledge about people with disabilities. They prefer to pay penalties to the state rather than employing people with disabilities. It’s not something that really helps a person with a disability,” says Alen.

Alen believes that anyone who invests in Goražde should receive benefits, but on the condition that they employ people with disabilities, especially since many jobs can be adjusted. After talking to the mayor of Goražde, he became motivated to continue working in his hometown, and he did not want to leave.

“I had the opportunity to leave the town, but Goražde is where I am at home. Every street is my house. All these people are mine, and I see them as a family. If I went to Sarajevo or anywhere else to work, I would lose much more than I could gain. So he [the mayor] gave me hope that I would be employed since he applied for the Fund for Rehabilitation and Employment of Persons with Disabilities.”

According to Alen, the Fund for Professional Rehabilitation and Employment of Persons with Disabilities recently announced a public call for grants for legal entities that want to employ someone with a disability or for those with disabilities who are self-employed.

“In my case, the Town Administration, headed by Mayor Ernest Imamović, applied within that public call, and, in the end, the Town Administration leadership received approval for the funds for my employment for one year. Now it is up to the mayor and town administration to complete the paperwork so that I can start working soon. I believe that we will not wait long for this to be completed so I can start serving my fellow citizens,” said Alen.

He explains that there are no social stigmas against people with disabilities in Goražde.

“You have no problems on the street; no one will ever call you derogatory names. The only thing you may encounter is someone who hesitates to approach you, which is justified because they do not know your needs or potential. But if you make a request or ask for help, trust me, you will get more than you asked for.”

The desire to be behind the wheel was always a dream of his, and he has finally achieved it. He says they didn’t have a vehicle in the beginning, so he often sat behind the wheel of his uncle’s car. He now drives without any problems, even though he had a few obstacles when taking the exam.

“Whenever he [his uncle] came, instead of spending time with my family, I spent time behind the wheel. I really love it. I think that the vehicle is kind of an orthopedic aid for me, and that’s how I use it,” he says.

Various obstacles, prejudices, stereotypes, and non-implementation of laws are obvious setbacks for those with disabilities in BiH and Serbia. Anja, Alen, Anđela, Marko, and Nemanja represent a statistical rarity but also a great step forward for employing people with disabilities. They are an example to all.

This article was created as part of the “Media for All” program realized by the “Young Journalists Competition” project with the support of the British Council.