Places that you visit spontaneously for the first time really have a special aura and soul. Just like that, with these emotions, my first trip to Rama was to study the traditional custom of tattooing among Catholics in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“Maybe there are two or three women left who have crosses in Rumboci village,” said Mare Vuročić, a grandmother from the village of Rumboci in Rama municipality. Mare was one of the people I interviewed during a visit to this village in northern Herzegovina, or southern Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), for research on traditional Catholic tattoos, sicanje.

Places that you visit spontaneously for the first time really have a special aura and soul. Just like that, with these emotions, my first trip to Rama was to study the traditional custom of tattooing among Catholics in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It goes by different names in different parts of BiH, such as bocanje or križićanje. For a long time, I was looking for the best possible example of traditional tattooing and tattoos, which are above all, the living history of a time and a dying tradition.

The idyllic landscape of the village of Šarci near Rumbok was illuminated by the colorful palette of the suns rays that day, when I spoke with Mare, Marta Šarčević, and Biljana Glibo. Mare was born in 1944 and Marta was born in 1938. They are relatives who are also tattooed in the traditional way. Biljana is an ethnomusicologist and leader of the ethnic heritage group ‘Čuvarice’ and she tattoos traditional designs, but with the help of modern tattoo studio equipment.

Sicanje tattoos were used by Catholic women to identify themselves as Catholics and thus save themselves from forced marriages, abduction into the harem, and rape during the Ottoman period. This method of tattooing in our country arose during the Ottoman occupation of medieval Bosnia and continued to be practiced extensively until the end of the Second World War. After the end of the Second World War, sicanje slowly disappeared into oblivion, but in certain areas, it can still be found.

During Ottoman times, anyone who was marked in this way would be prevented from converting to another religion, that is, to Islam. However, this was not always the case. According to the traditions collected by Croatian ethnologist Ćiro Truhelka, there is evidence that some Catholic women who were tattooed, but who still converted to Islam so they could marry the man they loved. A few months ago, I spoke with Toni Petković, a mythology researcher from Vareš. He also confirmed that in the Vareš area, there were also cases when tattooed women were abducted by the Ottomans or changed their religion.

According to one of the articles in the Glasnik magazine, published by the BiH National Museum, Truhelka and Dr. Leopold Glück were the first to talk about “common” tattooing, as it was called then. Marking religious, ethnic, or any other affiliation with tattoos was common at that time, but much more so among Catholics than any other peoples.

“When we were little girls, Mare’s aunt used to do it. That’s how it was in the old days, that’s what our people did to show that they were Croats during the Turkish occupation,” explained Marta, also a resident of Rumbok.

The girls who decided to get sicanje tattoos mostly did so between the ages of 10 and 15. Those I spoke to told me that they had done it at the age of 15.

“When I was little, this [tattoo] was done by your late relative,” Marta tells Mare, laughing.

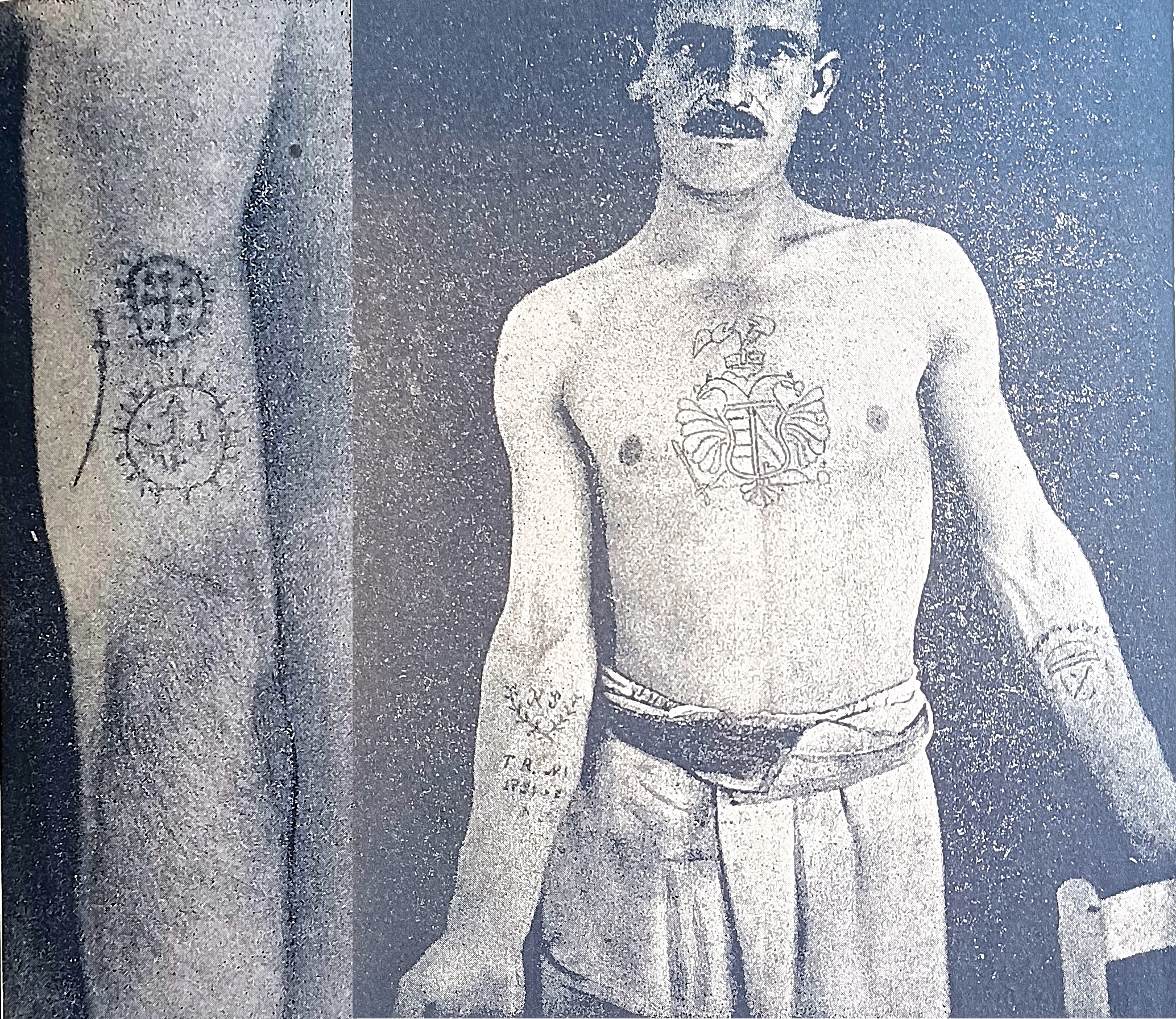

A question that really intrigued me was whether men also tattooed each other. The answer I received was “rarely,” to which Mare added, “It was so nice for us and us women wanted to do it.”

They confirmed that while “almost every girl had tattoos,” it was rare for men. Later in the conversation, Marta mentioned that her late brother had tattoos similar to hers.

Truhelka’s sources confirm that tattooing was more frequent among women. Both hands were tattooed, but according to Truhelka, the left hand was slightly more tattooed. Sometimes women had so many tattoos on their hands that the color of the hand wasn’t visible. Women tattooed their arms, above and below the elbow, as well as their hands. Chests were also tattooed along the sternum. Sometimes you could also see some simple design on the forehead. Truhelka says that in that period, it was mostly women from Central Bosnia who were tattooed, especially in the cities of Sarajevo, Visoko, Travnik, Fojnica, Prozor/Rama, Bugojno, and the Banja Luka area. The custom was slightly less common in Olovo, Vareš, Vijaci, and in the Neretvica river valley.

When men decided to get tattooed, they would get a simple design above their right elbow or a cross on their index finger. Towards the end of my trip in northern Herzegovina – or southern BiH, if you prefer – I had an informal conversation with Zdena, a priest from Guča Gora and a lover of traditional tattoos. He told me that men also used to get tattoos under their armpits or behind their ears. They even got designs from stećaks or traditional tombstones.

Sicanje began with a family gathering at the home of a female relative who was skilled in tattooing. According to Truhelka’s sources, tattooing usually began on holidays such as Midsummer Day or the Feast of St John (June 24th), the Annunciation (March 25th), St. Josip Day (March 19th), Palm Sunday (April 2nd), or any other day during Holy Week (the week before Easter, the most scared Catholic holiday). However, the grandmothers from Rumbok said that there was no specific date when it was done. The only thing that was certain was that it was done more often in the summer. About how many women would be tattooed in a day, Marta said, “however many you would like to receive, two or three. They would mostly come on Sundays when everyone was at home.”

From her sources, Truhelka states that women tattooed themselves, but the grandmothers from Rumbok refuted this, because when tattooing, the skin of the hand had to be held taught with the other hand.

“We were glad to do it. But it was hard, you know. Take honey, black ink, and mix. First, you draw what you want and then with a needle proceed to tattoo it,” said Mare. Marta elaborated, “from coal or crushed coal, honey, you would make the mixture. Take a needle, the one we used to sew with, and draw.”

Before the actual injection of this mixture, the design would first be painted with some black ink. Then, with a sewing needle, as Marta specified, one would tattoo into the skin until the design was finished.

“This is how [the skin] was tightened, you had to endure the pain. We would be covered in blood. It surprises me, but thanks to dear God, we never pierced any veins,” Marta said with a laugh.

After the tattoo was done, the hand would be wrapped in a bandage which would be worn for a whole day. The next day it would be washed with very cold water.

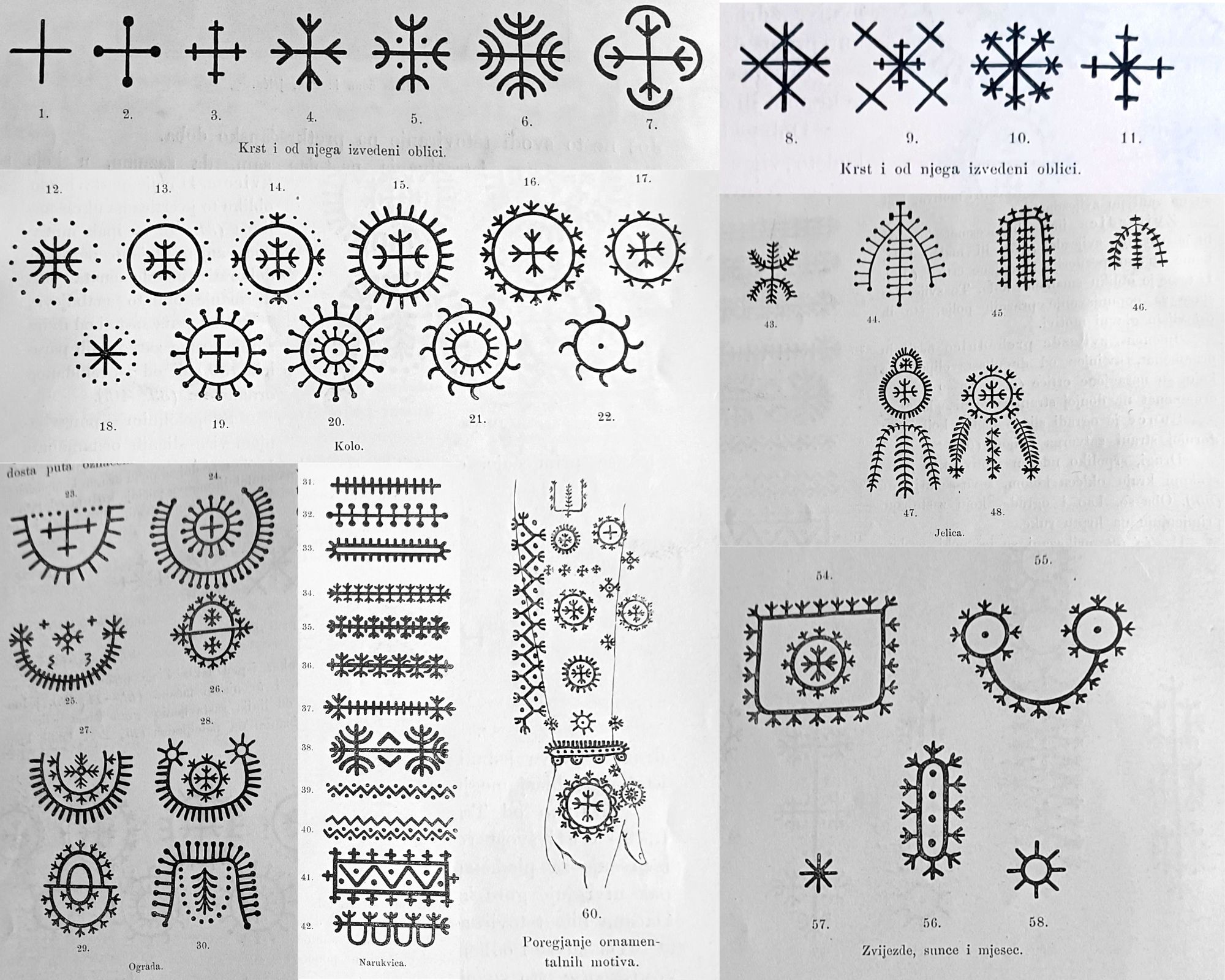

Crosses were the most commonly tattooed design, but not the only one. Certain sets of designs also developed that were characteristic of a particular place and had their own names. Crosses were usually placed on the finger, forehead, hands, or in the middle of some larger designs. The crosses numbered 4 to 7 in the photos below are called Fir crosses, because the ornaments at the ends of the crosses represent fir buds. In the area of Kraljeva Sutjeska, there were somewhat more ornate designs.

Then follows a series of secular symbols formed by dots or a circle, which were generally placed on the upper side of the arm, under the elbow, and on the chest. The circle usually had a cross inside, but more often it was empty, or with a single star (photo 18). The circles were usually concentric, with a smaller one inside a larger one. On men, the circle was placed above the elbow, while on a woman, it was on the upper arm.

The crescent shaped fence opens at the bend of the elbow. The other side facing the fingers is decorated with lines, berries, and fir trees. The inside contains a cross or a star with several lines, and the middle of the fence has a cross or some other design.

There is often a design below the fence, circling the wrist, such as a branch (photo 43). The more ornate designs in photos 44, 45, 46 are called fir trees. There are also variants where these designs adorn a wheel, as in photos 47 and 48.

The most common design in the Bila area is an ear of corn (photos 49 to 53), consisting of a vertical line, crosses, and twigs. It was often placed on the lower arm, below the elbow. The stars have shapes with eight lines (photo 57) or a circle bounded by lines (photo 58). The stars mostly served to fill the space between the main designs. The star composed of an oblong ellipse with lines on it was formerly called an ornament (photo 56). The sun is surrounded by a similar design and closed by a line on the upper side (photo 54). A sickle-shaped design with a wheel at both ends is called a moon (photo 55). Photo 60 shows the layout of the ornaments.

My travels through Rama ended with a conversation with Biljana, the ethnomusicologist and leader of the Čuvarice ethnic heritage group. She tattoos these designs because it’s her profession, but also because it’s a tradition that she loves and wholeheartedly wants to preserve. As she stated for Balkan Diskurs, today people react really well to these kinds of tattoos and she got a couple of questions from her former students who were looking for advice on what to do when they get a traditional tattoo.

Young people are still interested in traditions and this one from long ago still lives on, Biljana concludes.

Sicanje, although a long-forgotten tradition, is quietly returning to new generations.

1

Lana Lakić

This is such a good read! I wasn’t even aware the tradition existed until I had to do research for a story I’m working on. What a gorgeous tradition! This article is making me want to ask my mom and her older relatives about it to learn more.