The siege of Sarajevo, the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare, continues to be remembered for its brutal disregard for life. Nevertheless, amidst the grave destruction, daily shelling, and the constant struggle for survival, the people of Sarajevo refused to surrender. During this harrowing period, artists played a vital role, contributing to the birth of a culture of resistance in the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina and showing that the spirit of Sarajevo will never die.

Through their efforts, images from the Golgotha of Sarajevo traveled around the world. Moreover, these artists helped the people of Sarajevo preserve their spiritual identity, played a crucial role in preserving the spiritual identity of the people of Sarajevo. Resistance to cultural disappearance as well as the siege itself gave rise to a culture of creativity and resilience.

“Artists continued making art in order to uphold pre-war norms and as a means of coping with the extreme psychological stress that life under constant mortar and sniper fire entails,” said German historian Ewa Anna Kumelowski.

The siege of Sarajevo began in April 1992 and lasted a staggering 1,425 days. As confirmed by judicial verdicts, the deliberate campaign of shelling and sniping was carried out with the explicit purpose of terrorizing Sarajevo’s citizens. As a result, thousands of people were killed – men, women, and even children. Thousands more were maimed and wounded. The deep psychological scars and irrevocable trauma that so many Sarajevans endured remain with them to this day.

“We Resisted with Song”

Before the siege, Sarajevo was an important center for rock music in the former Yugoslavia on account of the numerous rock bands that originated in the capital, including Bijelo Dugme, Indexi, Plavi Orkestar, Crvena Jabuka, Zabranjeno Pušenje, and many others. With the disintegration of Yugoslavia, even the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina could not stop the music, sending the message that Sarajevo continues to thrive. Bands such as Sikter, Seven Up, and Erogene Zone helped carry this message to the world.

“Even during the war, for many Sarajevans, going to concerts was an escape from the harsh reality. It was a way to temporarily forget about the fear, pain, and uncertainty and to find the hope we all needed,” recalls Aida Tinjak, who frequently attended concerts and plays during the siege along with her friends.

According to Tinjak, it is difficult to say that attending cultural events during the siege of Sarajevo was either expected or unexpected, as it ultimately depended on the choices made by each individual. “For some people, going to a concert or play was too dangerous or impractical, while for others it was necessary to maintain their mental health and continue to fight against death,” Tinjak said.

Music was indeed a lifeline during the siege. The Sarajevo String Quartet performed more than 200 concerts over the course of nearly four years. Vedran Smailović, “the cellist of Sarajevo cello,” famously played Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor every afternoon for 22 days as a tribute to the 22 people killed by a shell explosion while waiting in line for bread on Vase Miskina Street in May of 1992.

In a statement for the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN BiH), Alma Alilović stated “Song was our medicine. We were children singing about peace, love, and our homeland, which we defended through song.” In 1993, at the age of 12, she joined the Palčić Choir, which operated throughout the war.

“To Be or Not to Be” in Sarajevo

According to Hana Bajrović Čardaković, author of the book and exhibition Theatre under Siege, the opening of the Academy of Performing Arts in the 1980s precipitated a vibrant artistic movement known as the New Wave. This period saw the emergence of new musical groups, as well as the production of plays such as “Tattooed Theater” and “Moon Show.” All of this had a profound impact on Sarajevo’s cultural scene at that time.

“In all that enthusiasm and new energy that the young, but also the more experienced artists brought to Sarajevo, the aggression happened. Sarajevo and its artists were unprepared for the war and everything that came with it. And maybe because of that, they continued to work and the theaters remained active throughout the years of the war,” Bajrović Čardaković explained.

Thanks to a dedicated group of enthusiasts, namely Dubravko Bibanović, Gradimir Gojer, Đorđe Mačkić, and Safet Plakalo, the people of Sarajevo were able to momentarily distract themselves from the insanity of war and escape the harsh realities of their daily lives. On May 17th, 1992, with the help of the acting community, they founded the Sarajevo War Theater (SARTR).

“An oft-mentioned story comes from Safet Plakalo, who says that after watching the play ‘Shelter,’ Sarajevo’s first wartime premiere, one woman wrote in the impressions book, ‘Thank you for helping me to not go crazy.’ I believe that this encapsulates the greatest value of the Sarajevo War Theater,” said Bajrović Čarkadžić.

The play “Shelter” was performed in SARTR’s first year of operation. This black comedy offers a satirical depiction of the daily life of Sarajevo citizens during the siege. The cast of the play included Senad Bašić, Zoran Bečić, Miodrag Trifunov, Jasna Diklić, Nebojša Veljović, Irena Mulamuhić, Alija Aljović and Nisveta Omerbašić.

“Not wanting in any way to impose judgments or set criteria regarding collective and individual interests, I must acknowledge a few facts. The Sarajevo War Theater, particularly Chamber Theater 55, followed by the Sarajevo National Theater and Sarajevo Youth Theater, made the biggest contribution to the field of performing arts,” stated Gradimir Gojer in the book, Opsada i Odbrana Sarajeva: 1992-1995 [The Siege and Defense of Sarajevo: 1992-1995].

During the siege, about 2,000 play reruns were performed, and 57 new plays were produced, which, as Bajrović Čardaković points out, isn’t far off from the number of plays currently produced annually in Sarajevo. The Sarajevo National Theater staged 11 plays, with the play ‘Bolero’ being performed 16 times in the course of the siege.

In addition to SARTR’s cultural contributions, it also played a role in Sarajevo’s defense. In August 1992, SARTR was established as a military unit at the Regional Headquarters of the Armed Forces of BiH in Sarajevo. Subsequently, on January 12th, 1993, it was designated as a public cultural institution of special importance for the city’s defense by a resolution of the War Presidency of the Assembly of the City of Sarajevo.

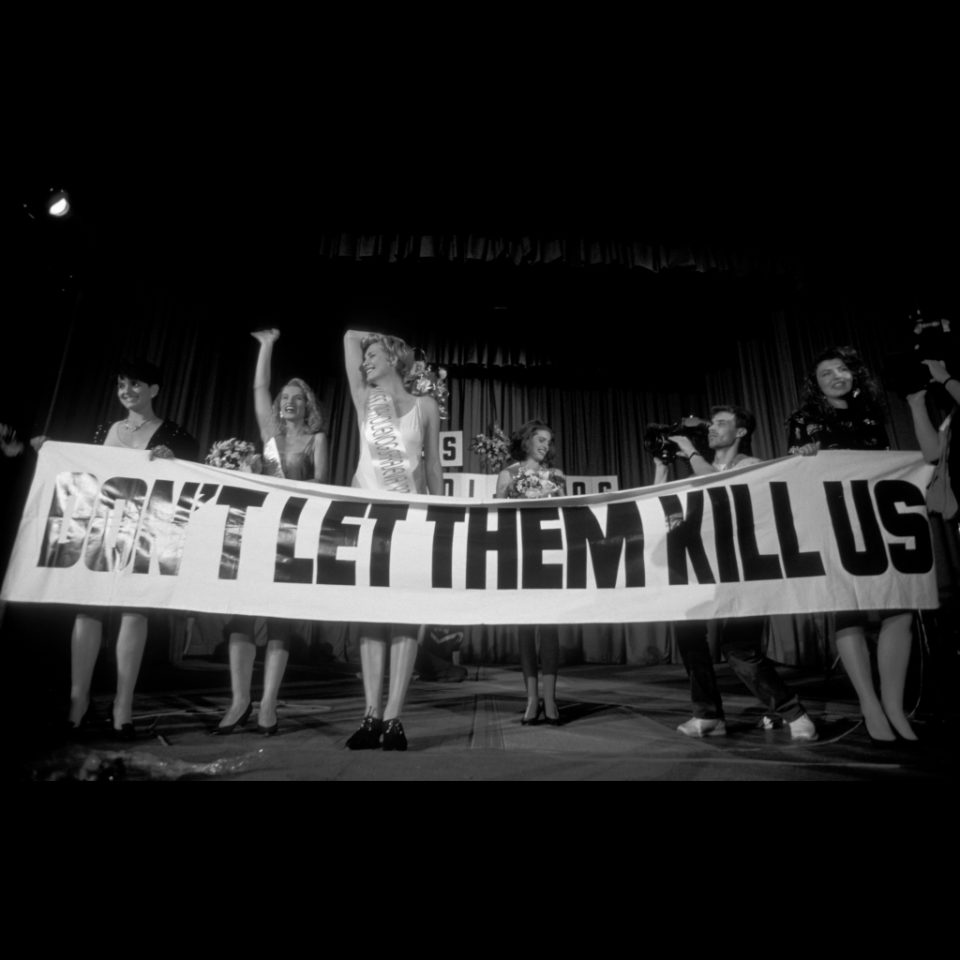

“A theater in the middle of a war in the middle of a besieged city signified civilization, it signified cosmopolitanism, it signified that people who are part of Europe and whose legacy is part of European cultural heritage were being attacked. The message from Sarajevo was clear: no matter what, you can’t destroy us,” said Bajrović Čardaković.

Unbreakable Bonds of Art

Mirsada Baljić, a Bosnian-Herzegovinian painter, highlights the significant role played by the Art Department in the cultural resistance of Sarajevo, alongside theater actors and musicians. Baljić led the department with support from Alma Suljević, Stijepa Gavrić, Ana Kovač, Dževad Hoza, Jasmin Duraković, Edin Numankadić, and others. They also initiated a collective exhibition project featuring fine artists active in Sarajevo during that time.

“The commitment to art helped us overcome all the adversities of those challenging times and connected us by unbreakable bonds. Today, even after so many years, we are proud of our activities at that time. We wanted to demonstrate what unites us amidst all our differences and enriches our existence,” said Baljić. During the siege, Baljić served as the director of fine arts in the Artistic Unit, making significant contributions to the cultural landscape despite the hardships of the time.

One of the most notable projects was “Artists of Sarajevo for a Free BiH.” After being exhibited in Sarajevo in 1992, the exhibition traveled to Ljubljana and Maribor in 1994 and 1995, and later to Fojnica in 1997.

“Time, as a concept, meant only uncertainty. Every moment of our existence was an inner existential scream, a sense of hopelessness, not knowing if we would be alive in the next moment. This gave us a sort of invisible armor of energy, strength, perseverance, optimism, and hope. We believed in a better tomorrow. It was difficult and many moments remain etched in our memory,” explained Baljić.

She emphasized the artistic immeasurable contribution and significance of artists during that challenging period, stating that “through various cultural events and expressions, we showed the world and image of spiritual resistance in the face of evil, establishing a kind of cultural dialogue with the world.”

After the initial shock, the people of Sarajevo adapted to the abnormal circumstances, leading to a revolutionary cultural transformation: the citizens embodied their resistance. Some continued to work, some planted vegetables in gardens while dodging snipers, some played the piano, some organized film festivals, some performed plays, and some sang.

“In this way, Sarajevan artists conveyed multiple messages to the world: intimate, political, intentional, or unintentional statements that diversely represented their unique experiences of the horrors of the siege,” said Kumelowska. She added that the visual arts scene was also remarkably productive despite the numerous limitations and dangers imposed by the siege. It even welcomed a number of established international artists, such as Christian Boltanski and IRWIN, and maintained, to some degree, connections with other cultural centers in the former Yugoslavia.

Art triumphed over death and the politics of aggression, not only through the sheer number of premieres, reruns, recorded songs, and painted works but also through the extraordinary creativity that opposed evil with art in the game of life

“Artists acted because it was their natural response. An actor’s need to perform is always present. This is their answer to every life situation – to portray what they have heard, seen, and experienced. To perform even when they have nothing else left. Cultural resistance arose from the artist’s decision to remain true to himself and to create life even while others are trying to kill him,” said Bajrović Čardaković.