BAFTA Scotland (New Talent) Award-winning photographer and filmmaker Chris Leslie began taking photographs whilst volunteering in the Former Yugoslavia in 1996. This led to the development of his career as a photographer, filmmaker, and communications manager for an international NGO documenting stories across Africa and Eastern Europe.

It all started when Chris graduated university in 1996 with a thesis entitled ‘The Forces Behind Nationalism and Ethnic Cleansing in the Former Yugoslavia’. As he himself says, these were 10,000 words that only gave a vague insight into the conflict but that, more importantly, started his obsession with all things Balkan. Lacking ideas on where to start his career path, Chris decided instead to look into volunteering in the region about which he had read so much.

While writing his first CV, he added ‘photography’ to the ‘Skills and Interests’ section, without ever having owned a camera nor taken a photograph. As luck would have it, he was soon invited to volunteer with an NGO in Pakrac, Croatia. His task was to teach black and white photography to children. This unexpected situation was the introduction to what would later become his life’s calling, and thus also began Chris’ long relationship and journey with the Balkan region and its people.

Chris’ Balkan Journey

“My whole love of photography started in the Balkans. That journey also determined the path of my career. Documenting peace and the slow rebuilding of a destroyed city resonated with me more than anything,” says Chris.

Many photographers became famous thanks to their images of the destroyed Yugoslavia. Many of them spent much of the war there documenting one of the darkest hours of human history. Later in the 1990’s, however, the international community turned its attention to other instances of global unrest. While other journalists, reporters and photographers began to engage in other conflicts to fulfill the daily demand for dramatic reporting, Chris Leslie had no idea that this region – the one that had already played such an important role in his student years – would change everything for him.

“I arrived in Zagreb, Croatia with somewhat sketchy photography and darkroom skills and armed with a donated Canon FT QL – a vintage 35mm camera – and Serbo-Croat phrasebook. Croatia’s capital Zagreb was in full late summer swing, packed out bars, restaurants, live music and cultural institutions aplenty. There was not a destroyed building or bullet ridden wall in sight. An hour or so into the train journey from Zagreb to Pakrac and this illusion of all being ‘normal’ was shattered as the landscapes and homes became increasingly bullet ridden and destroyed the closer the train got to Pakrac,” explains Chris.

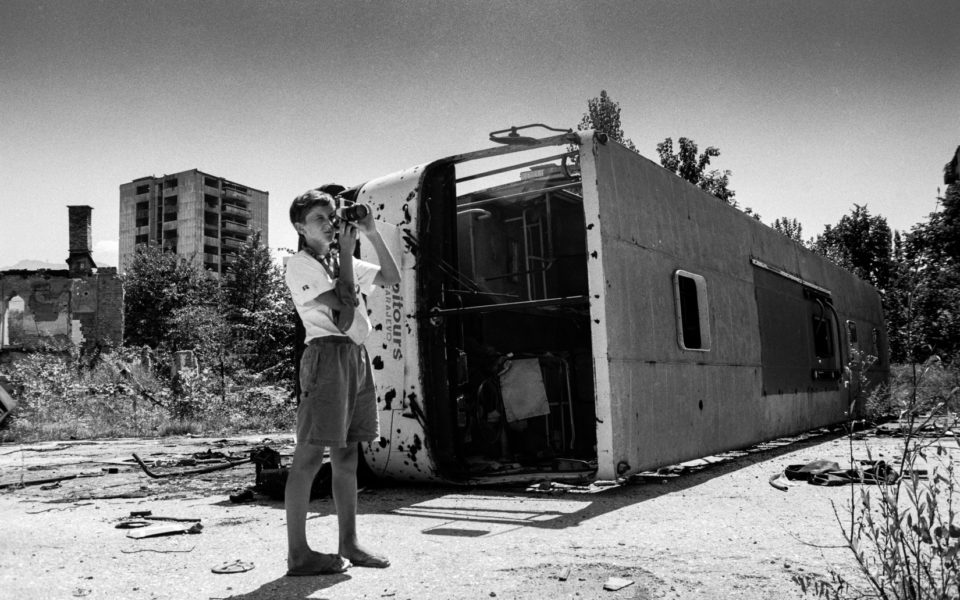

Chris’ early photographs are raw and unfiltered, just like the war itself. In them, we see the consequences of lives that carried on despite being surrounded by so much evil. His photographs reveal people attempting to live normal daily lives whilst the damage to their homes attests to the other very real reality of their situation. We see places of worship reduced to rubble and streets and homes pockmarked by bullets and bombs.

On the subject of why he chose to do peace photography, Chris explains that, although it is war that most interests other people, for him, it is the new struggles that peace brings with it that are the most interesting, and the least talked about. “Once the war ended, most of the media left and Bosnia and Croatia were no longer in the headlines, and yet that was a time of enormous change and rebuilding. I was really interested in how people managed to pick up the pieces and move on, and these were important stories that needed to be shared. The war may have ended but many people were faced with new frontlines.

Sarajevo Camera Kids

The end of the war enabled a more peaceful life to gradually return to the streets of Sarajevo. The city was enjoying its long-awaited peace, but Sarajevans had no idea that some new battles awaited them.

Although he spent four months in war-ravaged Pakrac, Chris emphasizes that nothing could really have prepared him for what he encountered in Sarajevo. “The destruction of the city was jaw-dropping, surreal and seemingly total: rows upon rows of broken, bombed-out high-rise flats; shell craters and explosion indents everywhere; hospitals, offices and factories all in ruins,” he writes evocatively in his essay A City in Ruins / Sarajevo Camera Kids. Chris recalls how a year later he would return to Sarajevo to start a project that would serve as a portal to a world that no longer exists.

Sarajevo Camera Kids is a photo project that was developed in the basement of the Sarajevo orphanage, Dom Bjelave, and the surrounding neighborhoods. Using equipment and resources donated by people from across Scotland, Chris worked with children aged 6 to 16, teaching them basic photographic techniques and film development.

Chris explains how he was a bit overwhelmed by the interest at first and how his classes were packed with children eager to learn about this exciting new technology, and to run around their neighborhood taking photos of the places where they played and hung out. Although, as he puts it, his “basic language skills did not extend to teaching the technicalities of photography”, the most important thing was that the classes were simple and easy to follow, and that the children had fun. “The intention was to provide a creative outlet for these children who had dealt with a near lifetime of war and siege,” he adds.

“The war was over and I think photography gave them something in a period when they had absolutely nothing. It gave them time, space and a new way to look at their city,” adds Chris.

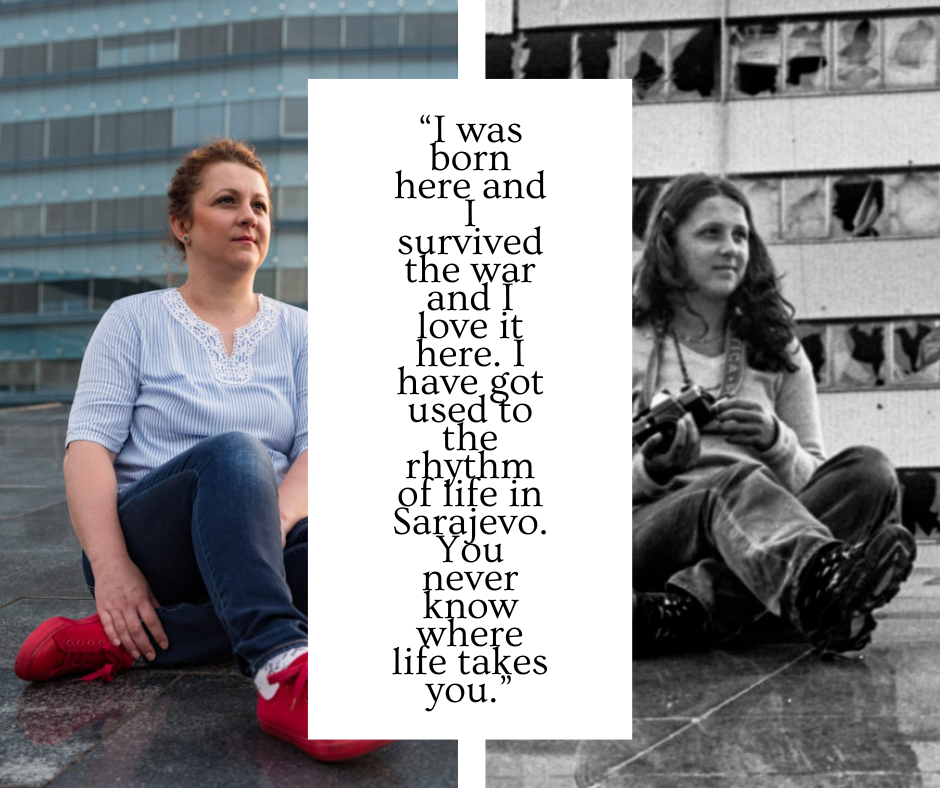

Although many anecdotes, memories and stories of great friendships sprung out of the three years that Chris worked on the project, one story in particular stands out for him. “There are a lot of memories. Perhaps the most vivid and memorable was when a young Oggi Tomić came into the basement as my first student. He grabbed the brush that I was using to clean out the darkroom space from me and explained I wasn’t using it properly. He then explained that he could get me lots of children from the orphanage to take part,” he recalls.

Sarajevo Camera Kids exhibition

More than two decades ago, Oggi Tomić, Dina Džihanić, Edina Hrnjić, Rina Trifković, Dženita Hodžić, Nusret, Muhamed Bošnjo, Jasmina Sabrihafizović, Amra Džihanić Barac, Senad, Mirnes Gagula, Sabina Demirović and Armin Demirović were experiencing the most devastating conflict in Europe since World War II. It attacked their city, their homes, and even their bodies. As children, they found respite in Chris and in photography.

As part of a project that includes the A Balkan Journey book, Chris Leslie opened the Sarajevo Camera Kids exhibition in Sarajevo on November 11, 2021, in partnership with the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), with support from the Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in cooperation with the City of Sarajevo’s Information Centre on the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. It is dedicated to Edina Hrnjić and the other children of the Bjelave Orphanage. The exhibition testifies to the long-term con – sequences that orphanages and war have on the orphans themselves.

“I’m just glad the Sarajevo Camera Kids – now adults – will get a chance to see their work exhibited, and for all of Sarajevo to see it too. It’s an important documentation of a time in Sarajevo’s history,” says Chris.

Chris hopes that both the exhibition and book will show Sarajevans how special this city is and how much it has changed and been rebuilt since the end of the war. The road is long, and the journey is not over, but the stories of these children must not be forgotten. Their story is not just theirs – it belongs to every child. Although the past cannot be corrected, it is in our hands that the future lies.

——————————

This article was initially published within the first edition of MIR Magazine. MIR, which means ‘peace’ in Bosnian is an annual publication and platform for young inventive people developed by the Post-Conflict Research Center and Balkan Diskurs. It is dedicated to individuals and organizations that left us a legacy of strongly built foundations to continue our fight for peace and justice.