It is hard to understand the killing of a child. The deliberate and ruthless targeting of children during the Siege of Sarajevo tragically illustrates the contrast between childhood innocence and war’s brutality. To commemorate the start of the occupation of Sarajevo, the documentary, “Djeca Sarajeva”, was screened for the first time on the 4th of April at the Sarajevo City Hall.

The film was the result of a collaboration between the Post Conflict Research Center (PCRC) and the Sarajevo Memorial Center, together with Pinch Media. During her speech, Founder and President of the PCRC, Velma Šarić, stressed the importance of creating films like this, which collect and preserve the narratives of the victims and their families.

Within the context of the 5th of May, the Day of Remembrance dedicated to the killed children of besieged Sarajevo, the documentary “Djeca Sarajeva” (The Children of Sarajevo) presents four different stories of child victims and their families. Their viewpoints, shaped by their personal ties to the victims, each offer a distinct lens through which the tragedy is perceived.

“Every tenth child was killed by a sniper [during the siege]” stated Fikret Grabovica, President of the Association of Parents of the Murdered Children of Sarajevo. “They were killed most often in moments of socializing, playing and relaxing”, and after long periods of hiding in shelters and basements, the children would eventually come out to play and unknowingly become targets to the murderers that were waiting for them. We know that the one who kills with a sniper knows exactly who he is firing a fatal shot at.” Socialization and play are crucial components of the development of children, and yet Sarajevo’s children would lose their lives for pursuing it.

An Unexpected Forever Goodbye: Miroslav’s Story

The tragedy of Marko, told by his brother, Miroslav Lukić, is based on his mother’s memories. On 26 July 1995, before his life was taken from him by a grenade, his family was supposed to leave for Croatia and then from there to Italy. From the perspective of a child, the life they have built in their hometown is all they know, and saying goodbye to their loved ones is a crucial moment.

Marko had gone to say one last farewell to his friends and grandmother, when a grenade was fired by Serb forces and killed him. “He died in the hands of his friends with whom he was saying his goodbyes a few minutes before,” noted Miroslav, taking a deep breath on camera.

Having been about to embark on a better future in a new safe haven, the tragedy resulted in their family never moving to Italy. “That’s something I am actually proud of,” Miroslav asserted to the interviewer confidently as he held back a tear. As he recalls this painful memory, Miroslav’s eyebrows are both raised, conveying an underlying tension and inner turmoil that threaten to overwhelm him at any point. The viewer finds themselves immersed in his vulnerability, as we witness the emotional toll the siege has had on children like Miroslav.

The Youngest Witness of Horror: Kemal’s Story

Kemal Karić was a baby during the Siege of Sarajevo. As his mother was heading for shelter, a shell fell behind her. The shrapnel killed her, while baby Kemal, whom she held tightly in her arms, survived. Kemal lost his leg, making him the youngest civilian to be wounded in the siege.

Although Kemal did not have a carefree childhood, he can hardly remember the 13 surgeries he had to endure because of the injuries he suffered on the day his mother died. What he does remember are the insecurities he experienced about his physical appearance growing up. Like every child, Kemal wanted to belong. “I didn’t want to tell anyone that I didn’t have a leg. I wanted to be like other children,” Kemal said to the camera. Now that he is older, he says he “overcame that fear” and is no longer insecure and ashamed to share his story with anyone. He now sees missing his leg and his mother as a part of him. “I don’t mind approaching a girl, saying I’m Kemal, I’ve lost my leg, I don’t have a mother because of the war.”

Whilst watching the film, the viewer cannot help but sympathize with Kemal as he recounts his childhood insecurities and his desire to belong. His journey to self-acceptance and overcoming those insecurities is a testament to his fortitude and courage. It is striking how he has embraced his physical differences and turned them into a source of strength rather than shame.

Most of us remember vividly our early interactions with our parents. For Kemal, they are missing. “I don’t remember a hug, I don’t remember anything. I have absolutely nothing from her…” Kemal says, while looking away from the camera. Despite her physical absence, he does feel his mother’s presence and parental advice during his daily life: “When things are hardest for me, it’s like she’s pushing me forward […] I’m sure she’s watching from above.” The absence of his mother’s physical presence is palpable in Kemal’s story, but the profound impact she has had on his life is undeniable. His goal is to honor his mother’s memory by becoming the man she would have been proud of, even though he never got the chance to know her. Kemal’s desire to make his family proud will resonate with many young adults navigating independence. Despite this similarity, Kemal’s journey is shaped by the trauma of war, which robbed him of his mother, setting it apart from the paths of his peers. His unwavering faith in her spiritual guidance and his determination to make her proud reflect the enduring bond between a mother and child that seems to transcend even death. While the scars of his childhood will remain with him, the viewer is struck by Kemal’s positive outlook. “I think she is happy with what I have achieved,” he concludes hopefully.

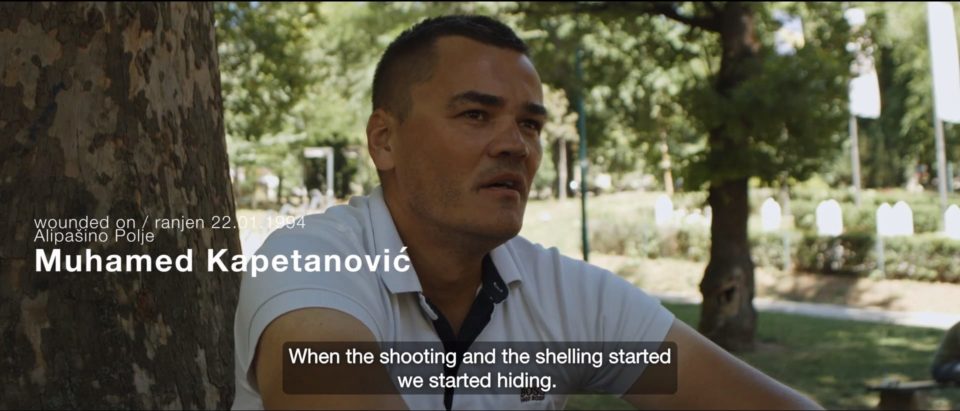

Remnants of a Destroyed Childhood: Muhamed’s Story

“Djeca Sarajeva” makes clear to the viewer that there were many children in Sarajevo who had an extremely direct and violent encounter with death. Like Miroslav and Kemal, Muhamed Kapetanović experienced it firsthand. He tells us how a sunny day of fleeting joy soon turned into a nightmare. “On the day that I was wounded, on the 22nd of January 1994, we had snow, but it was a sunny day, so we went out. […] At some point a grenade fell behind our backs.”

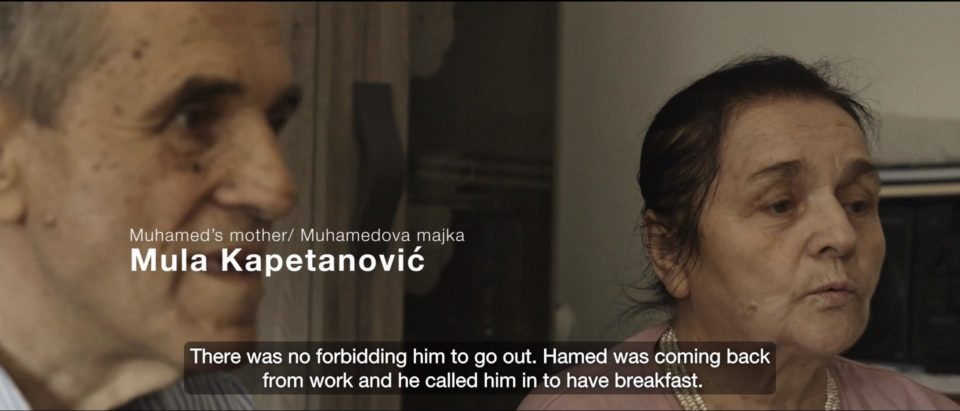

While Muhamed was one of the direct victims of the bombing, his parents have their own painful memories of that day. Hamed, his father, was returning from work when the first grenade landed. A man offered his car to transport the wounded and Hamed climbed in with him. Six children died that day, including two sisters, whom Hamed tried to help. “What got buried in my memory is, the driver said not to take the children who were massacred and dying, but to take those with a chance of being saved,” Hamed tells us, as he recreates the scene with his hands and shakes his head with profound sadness. Hamed’s message comes through loud and clear to the viewer. In war, there is no time, energy or resources to care for everyone, no room for real mourning.

Hamed and his son, Muhamed, tell us, not only with words but also with their body language, how much they suffered during the days of the siege. “At the beginning of the war we did not understand what the grenades were, what the dangers were,” Muhamed says while he takes a deep breath. It is that contrast between the innocence of children and war’s brutality, which the documentary “Djeca Sarajeva” portrays. Children who believed in the possibility of a peaceful day to go out and play, instead, found death and mourning. Part of that mourning has evolved into the search for justice. For Muhamed, this means justice for himself and for his friends who did not survive. That is why Muhamed accepted the Hague Tribunal’s invitation to testify in the cases against Stanislav Galić and Ratko Mladić. “I am very proud that he was brave enough to go to the Hague and to document what happened to him. Not only to him but to his friends, neighbors,” Hamed stated.

“Djeca Sarajeva” is not only a story about the past, but the living history of what life means today for all those victims of the Siege of Sarajevo. Muhamed, now 39 years old, still questions what can lead a person to organize aggression against civilians. “You always wonder […] How can one do it without their consciousness eating them alive?” Muhamed questions himself, as he clears his throat and recalls the trial at the Hague.

He remembers with particular sadness his friend Danijel. “Whenever I see his mother, I always remember Danijel. I always think about what he could have become in life. You simply cannot get over the fact that someone took him, killed him.”

An Eternal Emptiness: Barbara’s Story

“Try explaining to a child that he cannot go outside,” exclaims Barbara Jurenić, mother of Danijel Jurenić. Throughout the siege, Barbara was concerned for the safety of her children: “If I heard a bullet fired, that was a sign for me not to let the kids go out.” But Barbara recalls 22 January as being especially peaceful, emphasizing the absence of warning signs. On that unassuming day in 1994, her 11-year-old son Danijel, along with five other children, were killed by shelling while sledding near their homes.

When the shells were heard, Barbara ran outside amidst falling shrapnel and grenades to find her son. Among the smoke and sounds of children crying, she found Danijel lying face down, dead in the snow. To this day, Danijel’s memory lives on through Barbara who says there is no day that goes by where she doesn’t think of him and the horrors that occurred on that January day.

A mother’s love knows no bounds. Barbara’s bravery is testament to that. What strikes the viewer is how she placed aside her own safety in an effort to save her sons. Her remarkable display of bravery is something no parent should ever have to exhibit. Stories like that of Danijel and the other murdered children shared in “Djeca Sarajeva” illustrate the indiscriminate nature of war’s brutality. Viewers are left with the feeling that the killings impact ordinary citizens akin to ourselves, like Barbara, Muhamed, Hamed and Mula Kapetanović, Miroslav and Marko Lukić, Kemal and Adela Karić, and countless others.

Even in the midst of conflict, children are still children – no child anywhere should even have to bear the burden of war. Nor should their parents have to worry about their child losing their life to shelling when their child is simply being a child. “Djeca Sarajevo” is a documentary that brings home the contrast between childhood and war, making it a necessary watch for all.