Anna Idzigna explores the history and everyday work of Human Rights Watch, an international NGO that conducts research and advocacy on human rights.

On the fourth day of the 2015 WARM festival, members of the Post-Conflict Research Center attended the Human Rights Watch conference with Peter Bouckaert, a member of the Emergency Team of Human Rights Watch, Emma Daly, the Communications Director at Human Rights Watch, and Klaartje Quirijns, an independent documentary maker.

Human Rights Watch was founded in 1978 under the name Helsinki Watch. In the 1990s, the organization was operating in the Balkans during the Yugoslav Wars – a conflict that would have a fundamental influence on its work. Before the conflict, the main task of Human Rights Watch was to document the facts brought forth by investigators and later write reports about their findings. However, the horrors of the Balkan Wars were deemed to necessitate immediate international attention. Thus, while documenting facts remained an important task of the organization, it shifted its focus to facilitating the flow of information during conflict as a means of helping people.

Today, Human Rights Watch fieldworkers gather facts in order to both inform the writing of reports and engender immediate media attention. In particular, as many people do not have the time to read its detailed analyses, the organization tries to disseminate these facts and gain the attention of policy makers through as many channels as possible, such as press releases, blogs and social media channels.

To demonstrate the importance of providing information about conflicts to the public, Bouckaert showed the audience a video about the conflict in the Central African Republic. Bouckaert first arrived in the Central African Republic in 2006, by which point hundreds of thousands of people had fled their homes. He, together with his Emergency Team, then travelled throughout the country and talked to local communities as part of a fact finding mission designed to uncover, document and report the true horrors of the conflict. In 2013, after the anti-Muslim rebel movement Anti-Balaka emerged in same country, Bouckaert again went to local villages to talk with them about the actions they were undertaking.

Both cases are examples of how Human Rights Watch goes about its everyday work. The organization believes in the power of telling stories. Staff also believe that if they do not tell the story then no one else will. By putting people in the field, while working together with people who experienced the conflict, they aim to accurately publish facts with the goal of stopping human rights abuses. In this way, they try to put pressure on governments to intervene in conflicts. In September 2014, this worked in the Central African Republic, as a United Nations peacekeeping team was sent and the worst of the violence stopped.

Yet with all the media attention Human Rights Watch attracts, one might view the organization’s staff more as journalists than as criminal investigators. However, Bouckaert and Daly explained that this is a misconception. According to them, the task of a journalist is to tell a story, but the task of Human Rights Watch is to both tell the story and make a difference by putting pressure on the international community to intervene through the documentation and publication of factual evidence.

The panel cited several examples to underline this point of differentiation. Firstly, as opposed to simply checking the facts when visiting a site, Human Rights Watch fieldworkers also focus on gathering detailed information about the victims. Secondly, they try to find physical evidence that confirms the story, such as discarded documents or emails to superiors referencing their actions. Finally, fieldworkers also help people living in conflict areas to relocate to safer places.

The panel also discussed how the organization negotiates the challenges of reporting on the condition of human rights in more than 90 countries and territories worldwide. In each of these countries they cover both conflict-related cases and human rights abuses in general, but, due to security reasons, it is not always possible to have fieldworkers on the ground. However, this does not mean that they are not able to provide accurate reports. For example, the Syria Investigator at Human Rights Watch has conducted research through trained local contacts and activists for the last 10-12 years. In addition, recent advances in technology have increased the possibilities of ‘remote reporting’. The Syria Investigator at Human Rights Watch is also supported by a video expert who analyzes YouTube videos and satellite images to create a better picture of what is happening on the ground.

Finally, the panel also explained how a range of qualified experts support the work of Human Rights Watch’s criminal investigators and fieldworkers. One of the experts’ main roles is to check fieldworkers’ reports, verifying facts and asking the authors critical questions about the sources of information. This ensures a level of accuracy that enables the documents to be used in legal cases or by policy makers and governments. In addition, experts based at a regional level also help to decide which countries or conflicts should be considered as a priority.

Although it seemed Bouckaert loved every part of his job with Human Rights Watch, he admits that is by no means an easy one. Over the years he has found that, not only is it sometimes difficult to see all the horrors that happen in the world, it is also hard to lose so many friends through conflict.

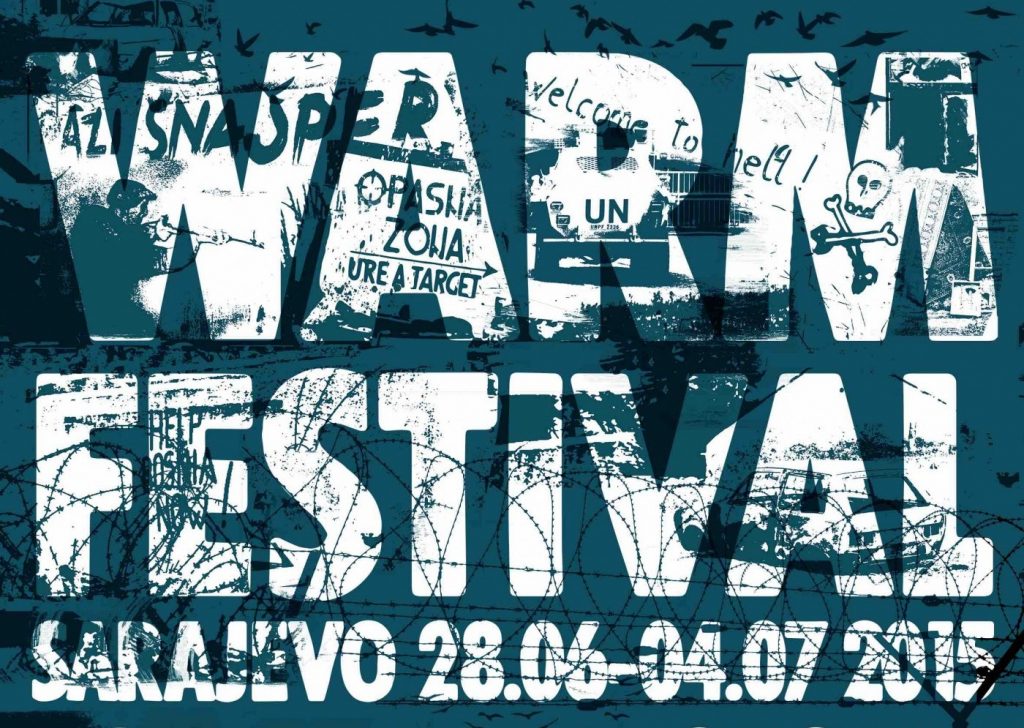

This article was published in collaboration with Warscapes. The WARM Festival took place in Sarajevo from Sunday 28 June to Saturday 4 July 2015. Run in collaboration with the Post-Conflict Research Center, the WARM Festival in Sarajevo brings together artists, reporters, academics and activists around the topic of contemporary conflict.