It has been eleven years since the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were established. While a number of challenges remain, the defense reform and subsequent unification of the forces offers an example of how carefully crafted legislation can support the advancement of post-war reconciliation and state-building efforts.

It has been eleven years since the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were established. While a number of challenges remain, the defense reform and subsequent unification of the forces offers an example of how carefully crafted legislation can support the advancement of post-war reconciliation and state-building efforts.

January 2017 marked the 11th anniversary of the establishment of the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina (AFBiH) and offered an opportunity to reflect on the progress achieved by the country’s defense forces throughout the past decade. Not without significant obstacles, Bosnia embarked on a defence system reform in 2003, prompted by calls from the international community. Within three years, the country made remarkable steps towards unifying its previously ethnically-divided forces while simultaneously assisting its Euro-Atlantic integration ambitions. Even though it will take many more years to resolve the remaining challenges, the defense reform has already been widely cited as one of the most successful examples of post-war legislation in Bosnia, with far-reaching effects on the ongoing reconciliation process.

Mirroring the administrative structure of Bosnia following the 1995 Dayton Agreement, the armed forces were left divided between the entities of Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) rather than placed under state control. The Army of the FBiH (Vojska Federacije BiH or VF) and the Army of Republika Srpska (Vojska Republike Srpske or VRS) were both oversized, conscript-based forces, divided along ethnic lines, and viewed each other as potential enemies. Within the VF itself, there were separate chains of command for Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces.1

By 2001, the need for a defense system reform emerged as it became increasingly clear that the forces were not just bloated and inefficient, but also constituted a considerable drain on public finances. RS and FBiH took the first steps towards transparency and accountability by agreeing to subject their 2000 Defense Budgets to external audits. The audits were conducted by a team of three international officers, and largely at the request of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

Audit results revealed the extent of mismanagement and misuse of funds that plagued the entity forces, including regularly exceeding the defense forces’ budget allocations, hidden costs and underpaying the staff. The key message of the audit, stated by the international community representatives and several domestic actors was that the state of the armed forces was no longer sustainable; neither entity would be able to afford their respective forces any longer without introducing significant reforms. It was under this pressure that both RS and FBiH went on to downsize their forces.2 Around the same time, Bosnia also made known its aspirations to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The changed attitudes toward the structure of the armed forces propelled by the audit and relentless pressure from the international community laid the foundation for what would become a full-fledged defence reform a few years down the line.

In May 2003, Jeremy ‘Paddy’ Ashdown, the then High Representative, concluded that “democratic civil oversight of armed forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina must be established at both the State and Entity level” and that “command and control at the State level” is essential in order for Bosnia to be fully consistent with its international obligations, and to help the country fulfill its Euro-Atlantic aspirations in the future.3 Ashdown, therefore, set up a Defense Reform Commission (DRC), nominating former US Assistant Secretary of Defense James R. Locher III as its chair. The main objective of the DRC was to examine the legal measures necessary to reform the Bosnian defense system and to draft relevant legislation based on their findings.4

The DRC members, drawn from both the international community and local institutions, had to operate within a challenging political environment from the onset of the project, often juggling multiple parties’ interests in order to reach a consensus. Despite such challenges, the commission released its final report entitled ‘The Path to Partnership for Peace’ in September 2003, following a remarkably rapid phase of consultation.

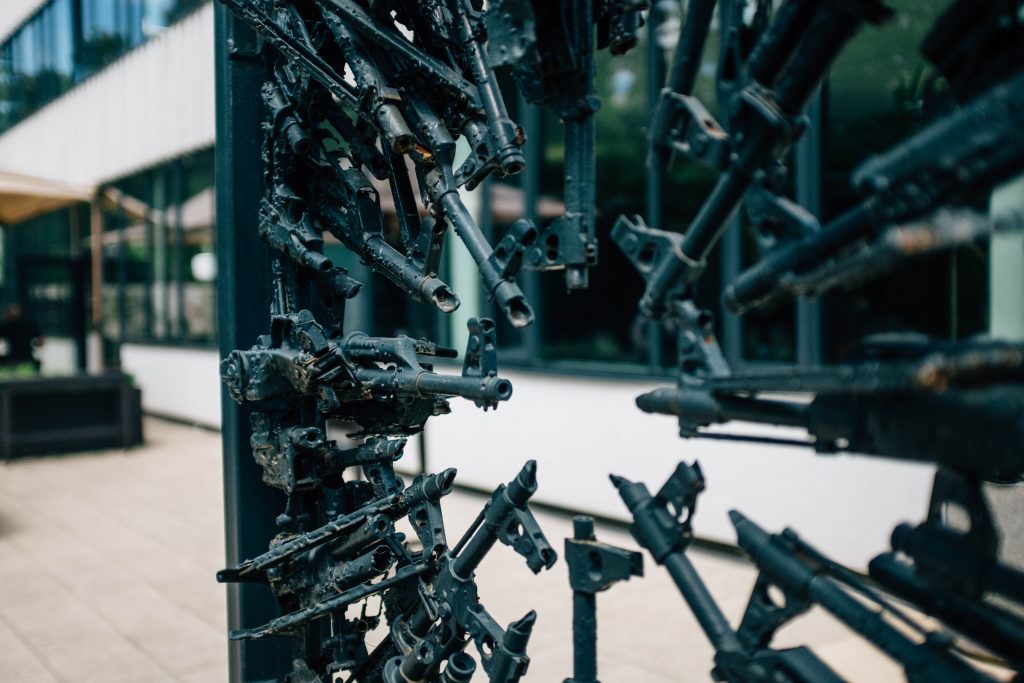

The report outlined the numerous shortcomings of the Bosnian defense system and laid out draft legislation to address specific weaknesses. Some of the most crucial measures outlined called for relegating the task of administrative management to the entities and placing the state in control of strategic and operational matters. The report also proposed enhanced parliamentary oversight and a stronger role of the presidency as the Commander-in-Chief, as well as explicitly called for a prohibition on the use of armed forces for internal security functions and political partisan activities, and a reduction of ammunition and weapons held by the forces, among other demands.5

One of the key roles of the report was to initiate reforms that, in the long term, would lay the groundwork for potential Partnership for Peace and NATO membership. The basic premise, strongly supported by the international community, was that closer Euro-Atlantic integration represented the most desirable course of action and that “Bosnia and Herzegovina should make an explicit commitment to joining NATO”. 6

The recommendations of the DRC report materialized in December 2003 with the enactment of a new Law on Defense. The law created a hybrid system whereby the VF and the VRS were preserved yet placed “under a minimal state-level command-and-control structure.” It was expected that a full integration of Bosnia’s armed forces would take place by 2007.7

The law also prescribed the establishment of a state-level Ministry of Defense, a Joint Staff and an Operational Command. However, both entities retained their own ministries of defense and authority over matters such as recruitment, training and funding.8

Although the reform encountered resistance from various actors within Bosnia, in particular, officials in Republika Srpska, it produced slow yet significant progress. During the first year, in 2004, a number of new state-level positions in the defence establishment were filled according to ethnic quotas and both forces significantly reduced their military personnel levels. 2004 was also the year Bosnia officially made NATO accession its foreign policy objective, a mission that would soon receive greater support from the newly-created NATO Headquarters in Sarajevo (NHQSa).9

In September 2005, the defense structure was again modified with the enactment of a new Law on Defense and a new Law on Service. The former handed full control over the armed forces to the state, creating a single force and doing away with the previous entity-based division. The latter provided for a volunteer professional force, ending the ineffective and burdensome conscription.10 These far-reaching modifications introduced by the laws were not universally acclaimed, however. As a result of both entities’ insistence on preserving some ethnic characteristics of the forces, a (ceremonial) regimental system, inspired by the British practice, was adopted.11

As a direct result of the 2005 legislation, Bosnia was invited to join Partnership for Peace in 2006, an offer the country accepted immediately.12 However, despite the remarkable progress achieved by Bosnia within ten years of signing the Dayton Agreement, a lot remained to be done to satisfy the NATO program’s requirements. One of the main points of contention was, and still is, the issue of defense property. According to the 2005 Law on Defense, all immovable property formerly used by the entities for the needs of defense, such as barracks or training facilities, should be registered and transferred to the ownership and management of the state.13 This was one of the key requirements of NATO’s Membership Action Plan (MAP), the final stage preceding full accession, presented to Bosnia during NATO’s 2010 Talin summit.14

Rohan Maxwell, the senior political-military adviser at NHQSa who participated in the implementation of the initial defense reform agreement of 2003, said in a recent interview: “Of the 63 locations, 24 have been registered to the ownership of the state of BiH and they’re all in the Federation. There are some that are in the pipeline, in a sense that they require something to be resolved. In Republika Srpska, nothing has been registered. We want to see a proof that BiH can come to an agreement on a difficult political issue, and then implement that agreement. This is the test that has been set.”

This requirement has not yet been met, delaying Bosnia’s participation in the MAP program and significantly hindering the completion of the defense sector reform.

Despite achieving the goal of unifying the previously hostile entity forces and replacing them with a slimmed-down, professional army — a feat inconceivable two decades ago — the Bosnian authorities have not safeguarded the new defense structure from political interference. The AFBiH remains a key battleground in the struggle for influence between the two entities, with Republika Srpska’s leader Milorad Dodik making repeated calls for cuts to the force or even its demobilization.15 Although great efforts have been made to unify the army, the very trade-offs required for its creation impede its full integration down to the operational level.16 The existence of the regimental system and ethnic-majority battalions does not represent a risk per se in terms of initiating inter-ethnic violence, but there are fears the current system would rapidly collapse in the event of such unrest.17

Nonetheless, from both technical and state-building perspectives, the legislation and the subsequent efforts that facilitated the creation of AFBiH serve as a positive example of governmental action, in contrast to other state reforms carried out during the same period, in particular, the police reform. Despite its protracted and often turbulent implementation process, the defense reform can serve as an example of a critical and meaningful attempt at post-war reconciliation and state-building in Bosnia.

—

1 Maxwell, R. and Olsen, J.A., (2013). Destination NATO. Defence Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2003-2013. [online] Available at: https://rusi.org/publication/whitehall-papers/destination-nato-defence-reform-bosnia-and-herzegovina-whp-80

2 OSCE, (2003). Affordable Armed Forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina. [online] Available at: http://www.oscebih.org/documents/osce_bih_doc_2003032815211560eng.pdf

3 Ashdown, P., (2003). Decision Establishing the Defense Reform Commission. [online] Available at: http://www.ohr.int/?p=65835&print=pdf

4 Ibid.

5 Defence Reform Commission, (2003). The Path to Partnership for Peace. Report of the Defence Reform Commission. [online] Available at: https://www.jfcnaples.nato.int/systems/file_download.ashx?pg=1441&ver=1

6 Ibid.

7 Maxwell, R. and Olsen, J.A., (2013). Destination NATO. Defence Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2003-2013. [online] Available at: https://rusi.org/publication/whitehall-papers/destination-nato-defence-reform-bosnia-and-herzegovina-whp-80

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Defence Reform Commission, (2005). AFBiH: A Single Military Force for the 21st Century. Defence Reform Commission 2005 Report. [online] Available at: https://www.jfcnaples.nato.int/systems/file_download.ashx?pg=1440&ver=1

11 Maxwell, R. and Olsen, J.A., (2013). Destination NATO. Defence Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2003-2013. [online] Available at: https://rusi.org/publication/whitehall-papers/destination-nato-defence-reform-bosnia-and-herzegovina-whp-80

12 Koneska, C., (2014). After Ethnic Conflict: Policy-making in Post-conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia. [online] Available at: https://books.google.ba/books?isbn=1472419812

13 Defence Reform Commission, (2005). AFBiH: A Single Military Force for the 21st Century. Defence Reform Commission 2005 Report. [online] Available at: https://www.jfcnaples.nato.int/systems/file_download.ashx?pg=1440&ver=1

14 NATO, 2010. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Membership Action Plan. [online] Available at: http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_62811.htm

15 http://www.b92.net/eng/news/region.php?yyyy=2012&mm=10&dd=05&nav_id=82523

16 Bassuener, K., (2015). The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Unfulfilled Promise. Atlantic Initiative – Democratization Policy Council BiH Security Risk Analysis. [online] Available at: http://www.democratizationpolicy.org/uimages/AI-DPC%20BiH%20Security%20Risk%20Analysis%20Paper%20Series%204%20The%20%20Armed%20Forces%20of%20%20BH.pdf

17 Ibid