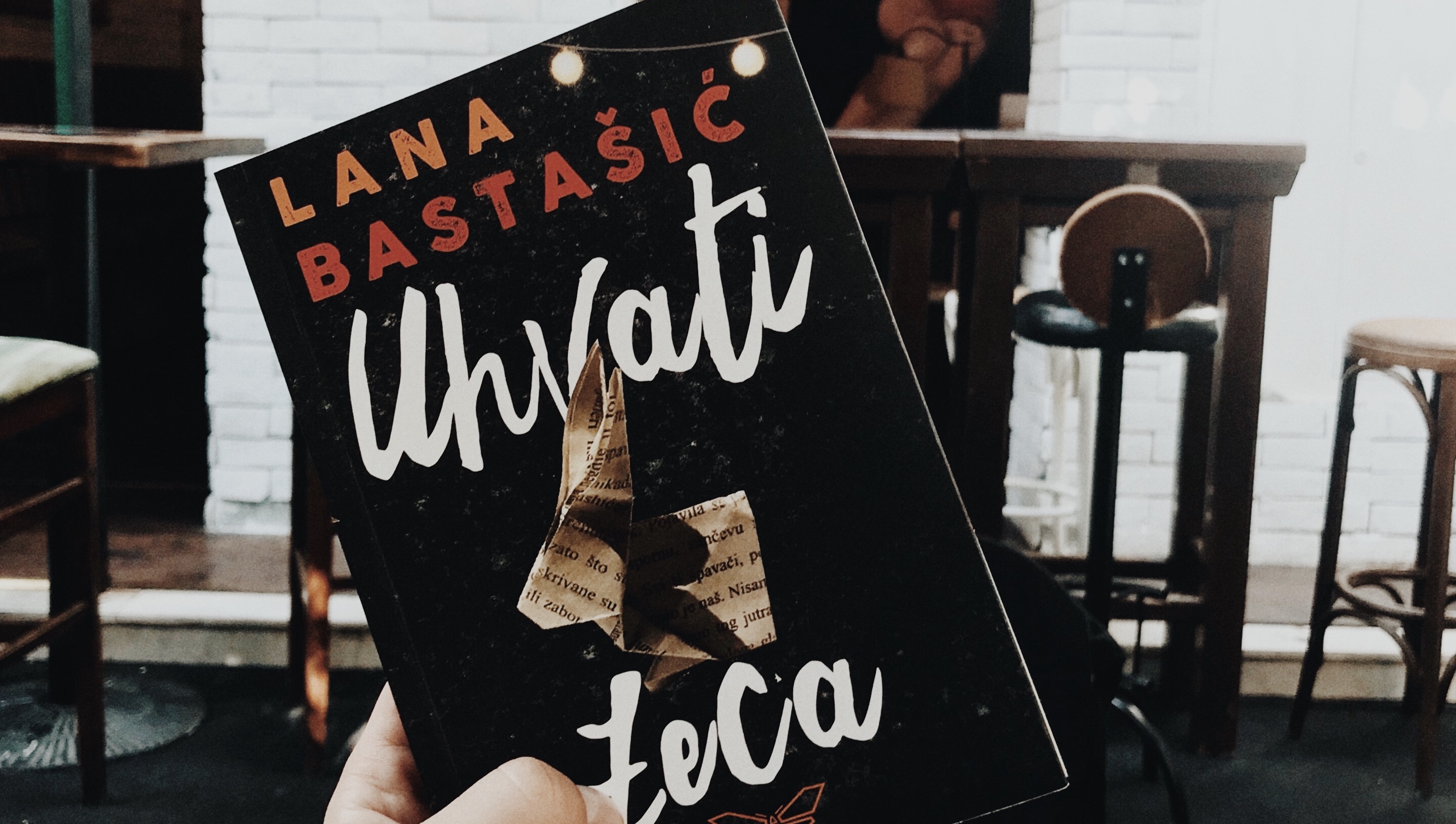

A road trip story only makes sense when the travelers, at least mistakenly, have a goal and believe that arriving at their destination will solve all problems and end all the hassles of the trip. There is no such goal in Bosnia; all roads are seemingly equally bumpy and pointless, leading you around in circles even when you seem to be making progress. Driving through Bosnia is different: “a twisted cosmic worm that does not lead to an external and real destination but to the gloomy, barely traversed depths of your own being.” These are Lana Bastašić’s words, whose latest novel is called „Uhvati zeca.“

The novel, whose name translates to “In Search of the White Rabbit,” features heroines who, like Alice, seek answers. Former friends Le(j)la and Sara reunite where it all began: in the hilly Wonderland of the Balkans. From there, the narrator takes us through a maze of childhood memories told in first person perspective. In „Uhvati Zeca,” through mistaken beliefs and distorted memory, we get a story of friendship, love, and one country.

The novel is also a story about Bosnia, but was written in Barcelona, where Lana edits a literary magazine, called ‘Carn de Cap,’ and runs a literary school. She was having trouble writing about a place from so far away–so she went on a road from Mostar to Banja Luka.

‘‘It was then that I realized that the Bosnia I was interested in was actually my inner toponym,” said Lana, “which had little to do with reality and geographical information, but with the memories and emotions of my storyteller. So that’s why this trip, at least for me, was like a kind of hypnosis in which you consciously decide to go back to the darkest parts of yourself and your growing up, to ’dig up’ the darkness that you have long suppressed and turn it into a text.”

Eventually, feeling she’d overdosed on Bosnia, she left Banja Luka. ‘‘Leaving helped me see what was left behind when I moved, and what were the things that had nothing to do with my place of residence, but solely with the internal nightmares that followed us wherever we went,’’ explained Lana.

‘‘Uhvati Zeca’’ is also a story about a war, which the author tries to treat from a different angle by giving voice to those who did not actively participate in it. “War is a story in which everyone has a clearly defined role: first of all bad guys and good guys, heroes and villains, and then mothers, wives, girls, children and old men, as well as the capital counted before and after the war. All of this, of course, depends on the storyteller. So it is not enough to talk about war if we go into the same logic that led to it: the logic of black and white divisions. I’m not interested in books about Serbs and Croats; I’m interested in books about people. Therefore, it’s necessary to address social and cultural traumas through the voices of those who did not actively participate in them and yet were affected by their consequences. In this way, we avoid getting into the same senseless naming game that, in its end, justifies the crimes,” said Lana.

The centerpiece of the novel, in between its various themes, is the story of two ex-friends who meet again after twelve years. Their friendship is held by a bond, which, for years, couldn’t be broken by diversity or turmoil. Society today and our cultural values, propagate the idea that one can only be complete after finding his or her ‘other half.’

‘‘The Balkans have gone astray so far on this issue. Lives in pairs are put ahead of happiness, so people endure in massively unhappy, bad, and even violent, marriages. The idea of solitude is scarier than that of being abused. As artist Sandra Dukić said it: happiness is not an argument for a Balkan woman,” Lana said.

This means that friendships often have to be put aside, especially by women. The narrator draws attention to this by talking about her relationships with men who always want to fix it but eventually fail, while her friend Lejla is the one who “knows how to release her from the barks.”

‘‘Female friendships have been put on the second or third shelf because we grew up in a society where we should look at each other as competition,” said Lana. “If the only way to achieve our identity is to be a wife and a mother, then a man is imperative in our lives, and other women are there to ‘defeat’ them, therefore they are the competition. Is there a better way of pushing aside a group than convincing its members that they are standing in the way of each other?”

Continuing on about female friendships, the author spoke about the popular belief that some topics are not sufficiently literary or serious. For her, the topic of female friendship is not especially literary; rather, she thinks that what’s being written about isn’t important, but how it’s written.

‘‘If we recall the greatest writers and their masterpieces, we soon realize that they were precisely those books that dealt with and transcended this type of elitism and which dealt with these ‘non-literary’ types and topics, Lana explained. “No topic is trivial if the writer can give it universality and, through it, say something about what being human is and what it means to be human today.” She added that it isn’t important to hear ‘‘women’s stories, but rather stories about women.” And not only that, she’d say the same about stories about the Roma, the oppressed, and all those whose stories we haven’t considered literary topics.

‘Grupa Pobunjene čitateljke,’ a group of independent critics from the region, released research about the literary scene from a gender perspective. The results, from 2019, show that Bosnia and Herzegovina has very few female authors. Lana thinks that changing this requires changing what happens as far back as elementary schools.

‘‘Virginia Woolf wrote about it in her essay ‘Professions for Women:’ as long as a woman sits down to write while asking herself if her writing will be accepted by men, she can’t ever write anything honest, and therefore nothing good,’’ Lana said. She remembered a distinguished professor telling her that he hoped she would be ‘‘a part of their literary community because of her charm.’’

According to Lana, if we live in a society that teaches us from a young age that our role is to charm, we can hardly build the assertiveness, even audacity, which writing requires. ‘‘How do you turn off all those voices and sit down and write something worth the paper?” she wonders.

Adding even more pressure is the feeling that you have to prove something extra because of your gender. Even if you’ve been given a prize or your book meets your sales targets, you’ll still need to justify your existence as an author, as if you’ve taken the place of some ‘real’ writer. Often, other women (writers and critics) are very harsh because they expect writers to correct all wrongs with one novel.

At this point, Lana returns to the idea that changes need to start from childhood: ‘‘So, let’s start today by teaching girls in the first grade of elementary school that it can be charming to disagree with something, that it is not against their nature to be interested in everything, not just dolls and dresses, that all colors can be theirs, that all toys can be for them, that they have the right to express their opinions without being accused of being ‘smart’… Let’s teach these girls that they are not flowers, but that they have a brain that can do everything that a boy’s brain can too. Then, in twenty years’ time, we will see true changes in the cultural and literary scene.”

She’s currently conducting research on some villages in the Balkans, looking into their superstitions and legends.

‘‘I hope that it will take the form of a novel in a year’s time. I don’t want to rush it because I think it is necessary to ‘cleanse’ from the previous book so that we don’t repeat the same story, in the same narrative voice and with the same characters,’’ Lana says, adding that she doesn’t really miss Banja Luka. ‘‘I miss the people in Banja Luka though.’’