Polish-born Jewish legal theorist Raphael Lemkin first coined the term ‘genocide’ in his 1944 work ‘Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress.’ Lemkin’s description of genocide as entailing “criminal intent to destroy or to cripple permanently a human group” laid the foundations for the Genocide Convention and genocide studies as a sociological discipline.

Lemkin’s model of genocide derived its form and exigence from the unfolding Holocaust and still recent Armenian genocide. The Holocaust particularly continued to shape the fundamental vocabulary of genocide studies as the twentieth century marched on. As cries of “never again” proved futile in Cambodia, Bosnia, and Rwanda, genocide scholars and media pundits alike cast ongoing mass atrocities in the mold of the Holocaust. Slobodan Milošević became the “Balkan Hitler,” Hutu extremism became “Rwandan Nazism” (Jinks, 2018).

Just as the Holocaust became the paradigmatic example of genocide, so too did Holocaust memorialization strategies for genocide memorialization initiatives at large. The “modes and aesthetics of Holocaust memorialization” have long influenced genocide memorials globally — sites of collective trauma have been repurposed as memorial centers where exhibitions highlight individual stories and big-picture narratives (Radonić, 2018).

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), the site of the first genocide on European soil since the Holocaust, is no exception. In BiH’s Republika Srpska entity, where genocide denialism has practically become institutionalized, the UNPROFOR Dutch Battalion’s former Potočari headquarters houses the Srebrenica Memorial Center (SMC).

Alongside Holocaust memory’s emergence on a global scale, debates have erupted in academia about the rhetorical implications of Holocaust referentialism. Can we draw parallels between the Shoah and other mass atrocities for the “articulation of [these] other histories,” as Holocaust scholar Michael Rothberg argues in Multidirectional Memory?

Or, does indulging Holocaust comparisons for understanding disconnected genocides erode the “uniqueness” of each history – a phenomenon which historian David B. MacDonald describes as ‘historical plagiarism’? How can we respectfully acknowledge and identify similarities between disparate mass atrocities? Does referentialism inherently dwell on a crude understanding of the comparative – a numbers game which degrades Holocaust memory to a yardstick of suffering?

Amidst these debates, genocide memorial institutions around the world have successfully cultivated relationships with Holocaust memorial initiatives which navigate the wrinkles of Holocaust referentialism. In BiH, one such collaboration between the USC Shoah Foundation and the SMC lays out a productive model for connecting Holocaust memory with those of other genocides.

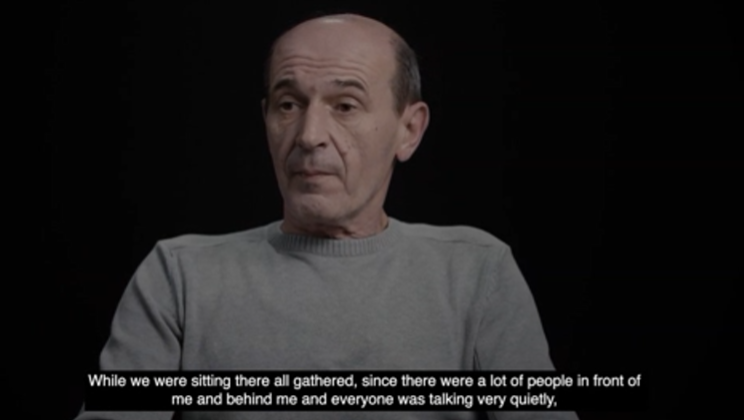

Earlier this year, a pilot collection of twenty survivor and witness testimonials from the SMC’s testimonial initiative was added to the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive (VHA). This recent step strengthens a groundbreaking partnership between an internationally-renowned Holocaust memorial institution and BiH’s foremost mnemonic institution dedicated to the 1995 Srebrenica genocide.

Each of the twenty testimonials are now being indexed with the USC Shoah Foundation’s 60,000+ keyword thesaurus before being incorporated into educational activities on war and genocide in BiH. Once complete, all resources developed with the SMC will be made available worldwide on the USC Shoah Foundation’s online educational platform, IWitness. As formal schooling around the globe continues to neglect adequate curricula on genocide, students will now have access to free learning materials on the Srebrenica Genocide alongside the USC Shoah Foundation’s lessons on the Holocaust and other cases of mass violence.

With this powerful material impact, the USC Shoah Foundation and SMC’s partnership follows several collaborations between the Foundation and other memorial institutions to shine new light on mass atrocities committed in Rwanda, Myanmar, Guatemala, the Ottoman Empire, and China.

As Dr. Badema Pitić, Acting Head of Research Services at the USC Shoah Foundation, points out, “Well-established Holocaust memorial institutions, like the USC Shoah Foundation, have much to offer to memorial initiatives focused on other genocides.”

In addition to “extensive experience and knowledge in the fields of genocide commemoration, research, and education,” Pitić notes the global audiences and government partnerships touted by Holocaust memorial institutions.

While Holocaust memorial institutions present large platforms to help smaller genocide memorial initiatives expand their audiences, institutions like the SMC themselves offer invaluable knowledge and research. Helmed largely by survivors of the Srebrenica genocide, the SMC maintains deep networks of trust within communities of survivors and their descendants. Such social capital has lent the SMC and similar locally-oriented mnemonic institutions the means to study and preserve traumatic histories.

As Sarajevo-based genocide scholar Dr. Hikmet Karčić explains, “Though every genocide is unique, certain shared concepts can be compared for a fuller understanding of genocide as a sociological phenomenon.” As researchers and students navigating the IWitness and VHA websites encounter testimonials from both Nazi-controlled Europe and Bosnian War-era Srebrenica, they can explore the social conditions – similar and not – which allowed for largely assimilated populations to be marked for extermination.