The pursuit of justice for survivors of sexual violence committed during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) offers valuable lessons for international and non-governmental organizations as well as other actors now working with the survivors of war crimes being committed in Ukraine more than 25 years later.

In the first of three parts in this series, we examine the extent to which insights from establishing accountability for wartime sexual violence in BiH can help in documenting and researching sexual violence in Ukraine.

During the 1992-1995 war in BiH, approximately from 20,000 to 50,000 women, men, girls and boys were raped or sexually abused. These findings established that sexual violence was a widespread crime and a weapon of war. Now, Conflict Related Sexual Violence (CRSV) survivors live in all parts of BiH and still face significant challenges in their daily lives.

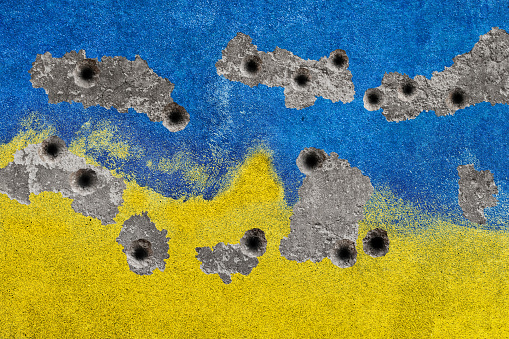

Ukraine has been embroiled in armed conflict with Russia since 2014, but on February 24th, Russia launched a country-wide invasion of Ukraine under the auspices of a ‘special military operation’ for the ‘demilitarisation’ and ‘denazification’ of the country (The Economist, 2022). This full-fledged invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, both of military personnel and civilians. Additionally, reports emerging from Ukraine contain accounts of widespread rape and sexual violence, demonstrating that CRSV remains prevalent in 2022. As CRSV entails devastating immediate and long-term consequences both for individuals and society, it is imperative to put adequate measures in place to address these problems.

Regarding the resolution of the CRSV issue in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also other conflicts, various initiatives have been undertaken with the aim of bringing perpetrators to justice as well as providing survivors with the necessary support. One such initiative is the United Kingdom’s Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (PSVI). Based on UN Security Council Resolution 1820, the Initiative focused on three key areas: challenging harmful attitudes towards survivors and victims of CRSV, delivering better access to healthcare and justice, and improving how security and peacekeeping forces prevent and respond to sexual violence.

Therefore, the first part of this three-part series on CRSV will evaluate the extent to which PSVI has helped to challenge harmful attitudes towards survivors in the pursuit of justice and accountability.

The initiative – launched by William Hague, then Minister of Foreign Affairs of Great Britain, and Angelina Jolie, special envoy of the UNHCR – resulted in the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence, which was signed in 2014 by 155 countries, including Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Protocol stated that its aim was to “not only be a vital practical tool that is improved and strengthened over time, but also a means of inspiring continued global attention, action and advocacy on this critical issue” to tackle crimes of sexual violence under international criminal law. As the first international protocol of its kind, the PSVI was praised for laying out a decisive action plan for efforts to end sexual violence in conflict. It also highlights the principle of ‘do no harm’ when interacting with survivors of CRSV, which is crucially important given the potential for victim re-traumatization in the course of obtaining witness testimonies and other interactions.

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) verified 43 cases of CSRV against women, girls and men in Ukraine, mostly attributed to Russian armed forces (OHCHR, 2022).

However, the OHCHR also recognized that it remained difficult to verify and assess the breadth of sexual violence which remains underreported. Furthermore, Pramila Patten, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict for the UN confirmed in an interview with AFP that rape is a part of Russia’s “military strategy” and is being used as a deliberate tactic of war. Patten stated, “when women are held for days and raped, when you start to rape little boys and men, when you see a series of genital mutilations, when you hear women testify about Russian soldiers equipped with Viagra, it’s clearly a military strategy” (France 24, 2022).

Empathetic Approaches

Globally, CRSV remains chronically underreported, and Pramila Patten stated that the reports of CRSV coming out of Ukraine were just the “tip of the iceberg” (Patten, 2022). This is due to a combination of factors including the logistical difficulty in accessing conflict zones and the stigma surrounding sexual violence which dissuades survivors and witnesses from giving statements. In an OSCE survey from 2019, 24% of Ukrainian women agreed that “violence against women is often provoked by the victim,” a consensus that highlights the extent to which Ukrainian society is still shaped by misleading ideas about sexual violence (OSCE, 2019). The international community is well aware of the difficulty of obtaining reliable statistics on CRSV during an active conflict and has protocols in place to confront this.

Adequate reporting and documentation of CRSV is crucial to achieving accountability and justice for the survivors. This objective was central to the PSVI and the Protocol as it was first and foremost a practical tool to promote accountability for crimes of sexual violence under international law (PSVI, 2014). Like approaches championed by the UN and international bodies, the PSVI is a survivor-centered approach with revolves around the needs, risks, and wellbeing of those directly impacted by CRSV.

In BiH, accounts of CRSV against women circulated primarily through witness statements and survivor testimonies in Western media. Consequently, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and inter-governmental organizations (IGOs) later began publishing reports on the subject as well. Within this environment, victims were routinely deprived of adequate and sensitive representation. Regarding the problematic representation of CRSV survivors, the journalist Linda Grant commented at the time, “there is something sexy, in media terms, about thousands of pretty Muslim virgins sobbing out their tales of sexual violation” (Anyone here been raped and speak English?, Grant, 1993). The sensationalism of stories on CRSV in BiH also led to many survivors being interviewed repeatedly, making them vulnerable to re-traumatization.

Since then, experts have taken steps to ensure that these practices are not repeated in any future efforts to obtain witness testimonies for the purposes of holding CRSV perpetrators accountable. In April 2022, the UK Government extended the PSVI to include the Murad Code to help combat problems in reporting and preventing CRSV. The Murad Code was created by the Prime Minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, Lord Ahmad, and Nobel Laureate and Yazidi Survivor of CRSV, Nadia Murad. In collaboration with governments, UN agencies, NGOs and CRSV survivors, the Murad Code is a practical framework that aims to ensure that survivors can have their experiences recorded safely, ethically, and effectively around the world. Crucially, the Code emphasizes 4 key principles: Understanding survivors as individuals, Respect survivor control and autonomy, Be responsible and have integrity and Add value or don’t do it.

Dubbed the ‘gold standard,’ these principles are one way in which the international community can try to achieve accountability and justice for victims of CRSV in Ukraine.

In September, Eurojust and the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC published practical guidelines for civil society organizations on documenting core international crimes to this end (Eurojust and ICC, 2022).

The section on victims of sexual and gender-based crimes echoes the Murad Code’s (2022) “need to be particularly mindful of the do-no-harm principle and be proactive in their efforts to identify assistance and support services available.” Importantly, the guidelines also set out a separate set of advice regarding male victims of CRSV.

Over the summer, special police groups for recording sexual crimes committed by Russians in Ukraine have been investigating CRSV in the Kyiv, Sumy, Chernihiv, and Kharkiv regions. Consisting of a group of specially trained police officers, prosecutors, and psychologists, the groups have, as of November 1st, begun work in the Kherson and Donetsk regions (OHCHR, 2022). This is part of the government’s comprehensive approach to investigating these crimes, which also includes the distribution of leaflets to inform civilians of the support available. The government’s approach thus represents a positive step towards ensuring justice for CRSV victims (IWPR, 2022).

International (in)Action

A large part of achieving accountability and justice in cases of CRSV relies on the mobilization of the international community to assist the victims. The Sarajevo-based feminist-activist organization Fondacija CURE argues Ukraine must be part of a global campaign to strengthen the international response to CRSV and the international community must partner with local actors, allocate additional resources for dealing with CRSV, and promote victim and survivor-centered approaches (Fondacija CURE, 2022).

Since the first reports of CRSV in Ukraine, the international community has acted with notable vigor. On May 3rd, the Ukrainian government and the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict singed the UN Framework of Cooperation. Aligning with Ukraine’s National Action Plan for Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, this framework establishes the basis for a partnership to prevent and respond to CRSV. This was the first international step to formalize an action plan regarding incidences of CRSV. However, the OSCE cautioned that the text of the framework agreement is quite general, and it remains to be seen to what extent the agreement will improve the lives of those affected by CRSV (OSCE, 2022).

Such proactive measures were markedly absent following the first reports of CRSV in BiH. The international community did act, but it took much longer for an adequate response to reach BiH. That being said, the collaboration between the international community and local, women-led NGOs was paramount to helping CRSV survivors, especially in places like Foča. NGOs focusing on CRSV sprung up around the country and played a critical role in providing support for survivors. Organizations like Vive Žene and Medica Zenica are still active today and remain a crucial resource for survivors of sexual violence.

Governments from around the world have pledged funds to help Ukraine deal with various consequences of the war, including CRSV. As part of their crisis response measure in August, the European Union donated €16 million to assist victims of sexual violence and support access to education (European External Action Service, 2022). Notably, the UK has announced a £2.5m support package to assist the Prosecutor General of Ukraine with investigating war crimes, including CRSV.

The United Nations Population Fund has also been instrumental in initiating support to CRSV victims in Ukraine. The launch of ‘Aurora,’ an online platform that provides support for survivors of gender-based violence, was followed by the establishment of a mobile app for women that have suffered or are at risk of gender-based violence. Disguised as a standard application, the app allows users to alert authorities by pressing an SOS button. These applications enable victims from all over Ukraine to access support 24/7 (UNFPA, 2022).

Since the first survivor relief center opened in Zaporiszhzhia on July 1st, there are now 101 mobile teams operating in 56 cities and communities in Ukraine. These support teams provide free medical, legal, and psychological assistance to survivors of CRSV in a safe environment, with the aim of main goal being to prevent the re-traumatization of survivors (UNFPA, 2022). These initiatives have been supported by the government of the UK, as well as the Canadian government, which contributed an extra CA$7m to strengthen the program (UNFPA, 2022).

Since the events in BiH in the 1990s, major advancements have been made to ensure that survivors of CRSV are treated with respect and sensitivity in the process of pursuing justice and accountability. It is therefore reassuring to see that new initiatives like the UK’s Murad Code are being successfully implemented to avoid repeating the harmful practices which characterized the process of documenting CRSV in BiH. In Ukraine, these programs and initiatives have yielded positive results, and it is imperative that they continue to receive the resources necessary to ensure that they can continue to operate at this level for the duration of the conflict.