What began as a temporary arrangement, “two schools under one roof” has now become an enduring example of segregation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with profound implications for long-term peace and coexistence in the country.

“There used to be a fence there,” says Tarik, pointing to an invisible line in the courtyard of Petar Barbarić school in Travnik. In front of him, a visible line still separates what was until last year a divided school. The building is painted in two colours, yellow and blue – a code that was used to mark the separation between the two major ethnic groups that have coexisted in Travnik since the end of the Bosnian War: Croats and Bosniaks.

His school was not unique: it was just one of 56 educational institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) operating under the so-called “two schools under one roof” system. This was an informal arrangement implemented after the war in the Federation of BiH, one of the country’s two territorial entities, in the ethnically mixed cantons of Zenica-Doboj, Central Bosnia, and Herzegovina-Neretva. However, what was intended as provisional solution soon became a permanent one, which has not changed since then.

These schools are not the only examples of segregation in the country. In Republika Srpska, all institutions adopt a Serbian curriculum. For example, schools attended by both Bosniak and Bosnian Serb students adhere to a strictly Serb curriculum, leaving Bosniak families feeling alienated and discriminated against within their communities.

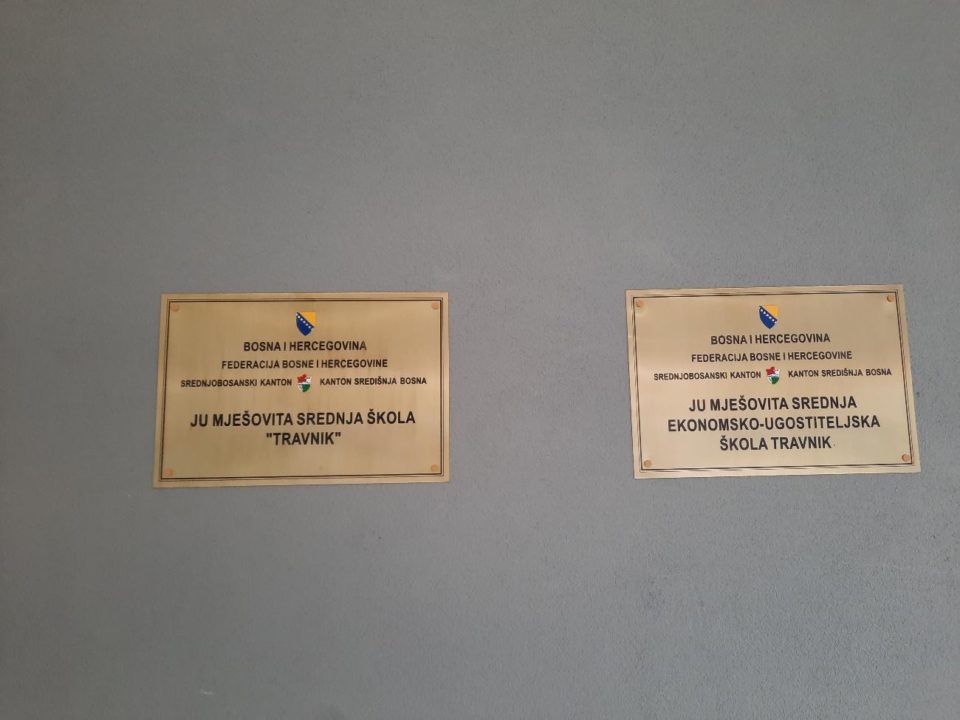

Meanwhile, in places such as Travnik, two schools under one roof ended last year, when a new school was built to accommodate Bosniaks. “Now we have two separate buildings, but it’s the same issue. We’re divided,” explains Tarik. Tarik is now a university graduate, but he remembers his experience as a student in Travnik very well.

He said that the entire system was made so that he didn’t know anyone who went to the other side of the school, and they didn’t know anyone from his side.

Not only were the curricula different, but there was also physical separation, as is the case nowadays in most of these schools. “We even started lessons 15 minutes before the Croats. The only way you could spend some time with them was through athletics or NGOs.”

Carving Identities in Stone

According to the OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the main obstacle to change in the post-war period has been a lack of political will. As they explain, both sides politically justify the existence of these schools as a way of reflecting their national identities, because they think that if they go together and learn in one of the languages of any other people, they will lose the unique characteristics of their identity. In other words, these schools are a way of carving identities in stone.

Dijana Mujkanović is a PhD Candidate at the University of Pittsburgh whose research has focused on the effects of inter-ethnic interaction. As far as she’s concerned, separating children along ethno-religious fault lines has no positive repercussions.

“It’s not really about preserving a certain set of core religious beliefs or cultural aspects; it’s actually about cementing those divisions,” explained Dijana.

The OSCE has a similar opinion: “Politicians are using the situation with the schools to send a clear political message that the Bosnian society is a divided one, where children can’t even go to school together.”

The consequences of being segregated from your peers since early childhood can last a lifetime. In 2018, the OSCE published a report denouncing the policy and calling it an obstacle to peace in the country.

Mujkanović says that the majority of voters are now the people who went through this education system as kids. These groups, which are already separated, can be easily manipulated by any side.

People who don’t have a lot of interactions with members of other groups in high schools, as Mujkanović explains, are unlikely to have those interactions going forward, resulting in deeper, and potentially irreversible, segregation among adults.

“It means that coexistence becomes parallel existence. We exist in parallel worlds, alongside one another but passing each other by,” Dijana reflects.

Contact Matters

Tarik remembers when a Bosnian Croat politician from the cantonal government visited his town and commented on the situation there between Croats and Bosniaks, “he came here and said that apples and pears don’t mix.”

Metaphors aside, such claims are dubious at best, Mujkanović believes. In reality, we see innumerable examples of diverse communities in which children learn to live together with members of other ethnicities long before they are taught prejudice.

“One of the things that we need to keep in mind when we’re talking about schools is that we have two very important characteristics of contact there: one is that it occurs at a younger age, and the other thing is that it’s continuous. If you start having relationships with people of different ethnicities or from other groups, they are likely to stay there over the years,” says Dijana.

For this researcher, contact from an early stage between people from diverse backgrounds is essential for creating a more tolerant society. “Contact demystifies the other and makes it so that it’s no longer really a question of ethnicity. It personalizes the other, draws them out of the collective and allows us to see the individual.” She believes that putting members of different ethnic groups together enables people to see the diversity in the other group.

“The important thing about contact is understanding that there’s diversity and understanding that groups can’t be generalized in certain ways as being bad or good,” explained Mujkanović.

The Impasse

In July 2016, students in the Central Bosnia Canton, including Tarik, took to the street to protest the decision to implement the “two schools under one roof” policy in the town of Jajce. “The protest took place here,” he says, referring to Travnik.

“Many people from my school went, and they were successful because the school in Jajce wasn’t built.”

Despite the success of the protests, this was treated as an isolated case. The system itself was not called into question and the practice of separating students on ethnic grounds continued. Two years later, activists again tried to persuade politicians and the international community to reject this policy, but interest in the issue has since diminished.

The OSCE explains this impasse as the result of a political system that is not receptive to the demands of these young students.

“I think that young generations are sending a very, very strong message that they do not accept this system, but they’re not willing to spend their life changing the minds and the values of the country,” was explained by the OSCE Mission.

Mujkanović agrees, specifying two factors that contribute to the inertia of the education system: “One is just the general impasse, with the current situation, people are simply exhausted, they’re tired, they don’t feel like anything they think or feel matters. And I also think that the baseline of what is normal has shifted. People have lived this way for so long that it just becomes the norm. It’s the default. And those are the hardest things to attack and change.”

Challenging the Status Quo

Despite the difficulties, not everyone has given up. Some civil society organizations are slowly challenging “two schools under one roof” at the local level, although this is often far from the headlines. This is the case with Nansen Dialogue Center (NDC) Mostar, an NGO that promotes dialogue between ethnic groups as an instrument for sustainable peace. In 2008, they started working on education in the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton. As they say, they couldn’t keep their eyes closed when it came to two schools under one roof because they even had some of these schools on their street.

They have succeeded in implementing a dialogue model in extracurricular activities for Croats and Bosniak students to cooperate. “We really wanted to establish common ground for students to come together, so we started to involve them in organizing different kinds of community projects, like setting up the school magazine,” says Vernes, an NDC Mostar officer.

They select groups of 30 students from each ethnic group and put them together with four teachers, two Croats and two Bosniaks. Although they faced certain difficulties, such as resistance from local authorities and the concerns of the student’s parents, they were able to overcome them and Vernes considers their model a success.

“The teachers are kind of role models for kids, they are cooperating and communicating. And I believe that students and kids interacting and having fun participating in all these programs really sends a positive message that there is an alternative to the current educational model in Bosnia Herzegovina,” said Voloder.

Outside civil society, there are other voices emphasizing that education without segregation possible. Mujkanović is one of them. She believes that cultural identities can be protected without enforcing them in the school.

“We don’t need to necessarily think of initiatives to separate people within institutional structures, these initiatives only originate from the politicians,” she adds. In her opinion, religious activities and cultural traditions can still be present in the extracurricular sphere, while having common courses and curriculums.

However, the issue remains of which subjects can be unified. History, for example, is taught differently in Bosnia depending on the community one belongs to. Tarik is against “two schools under one roof,” but he doubts that the Bosnian society can reach a consensus about its past.

“We don’t have a common history and creating it is almost impossible.” Mujkanović disagrees, however, arguing that objective facts can be taught and then a dialogue can be created around contrasting interpretations. “I can imagine textbooks where those conflicting narratives are put in conversation with one another with clear learning objectives.”

But all the forces of change in Bosnia must confront one inevitable truth. Every year there are fewer young students in the country and their voices are losing power.

“In this region, unfortunately, we are losing the only source of change that we have”, says the OSCE.

In Travnik, “two schools under one roof” ended last year after the construction of a public school that is now used almost exclusively by Bosniaks. Tarik says it was supposed to be one of the best public high schools in Bosnia, but that now that it’s finished, the question remains of who it was built for, since every year, there are less children.