For some, maps serve as a streamlined tool to help one get from point A to point B. But for the team of the Subjective Atlas project, the act of cartography itself represents a complex journey informed by politics, history, and the personal relationships we have to the landscape in which our lives unfold.

For five days, local and international youth in Sarajevo have had the chance to explore the world of cartography and artistic expression by mapping their own lived experiences in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). The Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC) has dedicated resources to host the Brussels-based Subjective Atlas project, for which participants were to critically engage with their personal and geographical surroundings by mapping an Atlas of BiH.

The premise of the project is to push back against singular, top-down narratives that claim to present objective truths about a region, and instead document places from the “bottom-up.” Through photos of shared and personal cultural experiences, such as the documentation of daily routes, architecture, personal belongings, and unique cultural phenomena, both creators and readers of the Atlas can visually understand what it means to live in that place while making space for the complex identities that exist in every individual.

“We first started with creating the map of our country from our personal experience and now we are working on flags.” Jelena Ostoić, a Mostar-based psychologist and workshop participant told Balkan Diskurs. Through artistic practices, including crafting and map-making, young people at the workshop were encouraged to creatively depict how they perceive and understand their own environment, country, and culture.

The collection of their contributions will be turned into a physical atlas of Bosnia and Herzegovina, to be published next summer. In this type of map-making – the practice of counter-mapping – the process is just as important as the destination.

Subjective Atlas: a history of counter-mapping

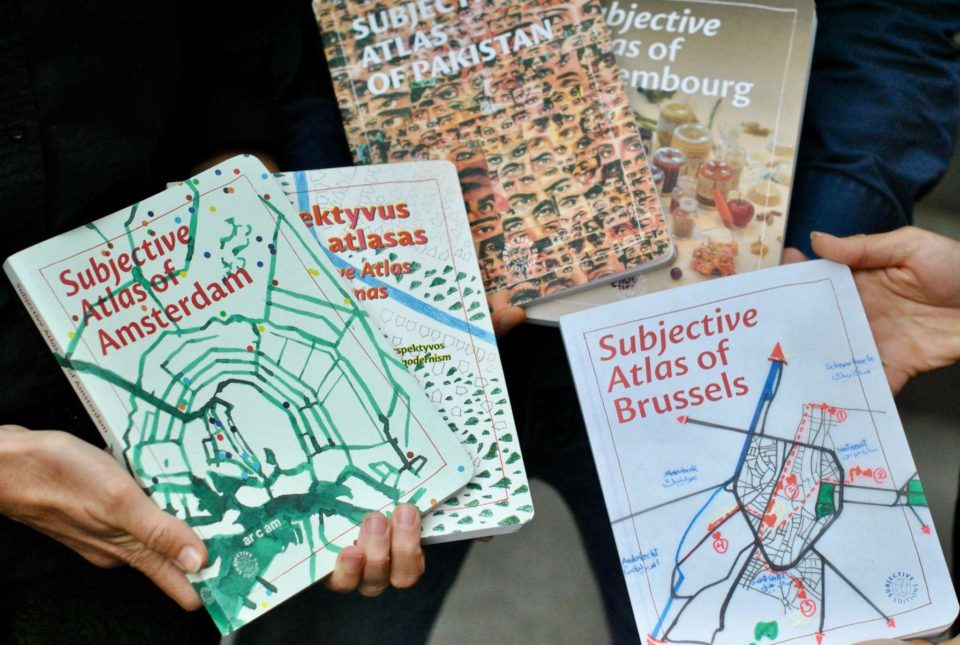

In 2003, Dutch designer and researcher, Annelys De Vet, travelled to Tallinn to capture Estonian perceptions of the European Union given the EU’s enlargement eastwards that increased the number of its members from 15 to 25. De Vet observed that despite this unparalleled expansion, the EU’s collective visual imagery remained the same. To engage these underrepresented imaginaries, her workshop encouraged Estonian participants to create their own flags, maps, and projections on what the EU and Estonian accession meant to them. The resultant “Subjective Atlas of the EU from an Estonian Point of View” marked the onset of the Subjective Atlas series, which would spawn a total of 13 more cartographic publications before its team made their way to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In a workshop and an interview with PCRC, De Vet, founder and editor-in-chief of Subjective Atlas, shared the vision of this counter-mapping venture. “How our perception of the world is being informed (…) through atlases, through cartography – it often represents quite a singular worldview.” The act of mapping holds tremendous political power, though it is rarely acknowledged as such. De Vet elaborated that the institutionalised, top-down nature of maps and cartography tends to go unremarked, and unquestioned. Official maps rarely articulate the conditions under which they are made, even though they are human-made, subjective constructions of a shared socio-political space. Instead, such maps claim to present a “singular truth,” supposedly position-free and untouched by the power dynamics and inequalities that govern their production.

In response, Subjective Atlas seeks to act as a platform for plurality, creating alternative maps from the bottom up through artistic practices and everyday realities. To demystify the practice of map-making, De Vet and her team invite local participants to create maps “that allow different ways of identification, different ways of belonging.” In this process, “people who inhabit the space” map their environment from their own experience and “situated knowledge.” James Riding, researcher in human geography from Newcastle University, explains that landscapes, places and experiences hereby come into play as counterforces to state-based renditions of mapping.

Riding also stresses how, to engage with Bosnian youth and collect their imaginations about their future in BiH, Subjective Atlas needed to forge connections with a local organization like PCRC first. The team reiterated how local partnerships are paramount to their work, and how they only conduct workshops in countries upon invitation. This process of relationship building can be quite long. Riding himself has spent ten years in Bosnia to build a base of contacts that would grant him a local network for his academic work. He underscores how such a method is needed to gain trust and reputation that such work will bring “diverse voices together in a sensitive and careful way”. For him, it’s vital to make space for complex identity and not replicate the “simplistic straightforward narratives” of division. Rather than reinforcing a singular narrative that flattens individuals to just their ethnicity, Riding’s research seeks to embrace the complexity and creativity in each individual’s experience of a landscape. Thus, Bosnia and Herzegovina presents an ideal model where the requirements of invitation, partnership, and the need to publish the creativity and uniqueness of a complicated landscape and the people inhabiting it are all present.

Participation through artistic practice

Subjective Atlas’ workshops encourage participants to share the lived experiences of their environment through artistic expression. This methodology aims to both challenge and sidestep vocal and written language as standard means of producing and conveying knowledge. “We carry a lot of knowledge in our bodies, in our memories, that is not often (…) being expressed,” explains De Vet. Participants’ visual communications take centre stage in the Subjective Atlas project, whose methodology aims to activate forms of situated, non-institutionalised knowledge.

The expression thereof, however, requires some practice, as stated by Brussels-based performance artist Sana Ghobbeh, who joined Subjective Atlas as a coordinator and supports the series in its artistic component. Though much of her work is text-based, Ghobbeh equally deals with problematic architectural and public spaces. “In that sense, I think I’m super conceptually connected to the project.” She emphasised the “different dynamic and energy” each atlas carries, all the while highlighting the universal importance of the visual in their respective editions.

Though many workshop participants initially approach the workshop with reservation, seeing previous examples of the ever-growing series inspires them, and renders them more comfortable in creating their own contributions, says De Vet. She equally stresses that such a participatory environment benefits from a culture of transparency, safety and hospitality – factors feeding a “joyful energy, allowing for [the right] conversations to take place.”

According to the team, these very aspects also play a central role in the workshop’s inclusivity and accessibility. The project selects the locations for their atlases based on local initiative and partnerships, and therefore relies heavily on the contacts and infrastructure provided by its partnering organisations on site. Insofar, marginalised groups and their voices are sought-after through these channels to reach certain levels of diversity in terms of the participants’ gender, ethnic and religious background, and age.

Part and parcel of the series is to get participants to recognise and engage with their backgrounds, and understand how this subjectivity shapes their perceptions of the world around them – a process reflected in the maps, flags, and other creative contributions produced throughout the workshop. While this aim renders the atlas an inevitably political item, De Vet and Riding underscore that it is “not a place for propaganda.” Rather, they expand, the atlas seeks to communicate “the complexity of the human being” by collecting a range of voices that, together, build a unique societal context.

The Atlas and its many audiences

The life of the atlas continues well beyond the workshop. In its post-production, it addresses audiences aside from its initial participants. Subjective Atlas’ Creative Commons approach facilitates the reproduction and dissemination of its content through events, exhibitions, republications, and follow-up projects. The subjective maps, flags, and other contributions thereby speak to both internal and external audiences. Locals and other individuals relating to the place addressed, as well as diasporic communities frequently take substantial interest in the publications. However, in the past, reflections produced in the Subjective Atlas series have equally entered into official and institutional contexts. The “Subjective Atlas of Palestine,” for instance, was embraced by local officials as a gift for visiting internationals.

This attests to the elasticity of such a deeply personal and yet profoundly socio-political project to contribute to a larger discourse on cartography and plural identities. The objective “to demystify cartography and stress other ways of expressing belonging to a place” stands at the centre of the Subjective Atlas series. De Vet further expands on the project’s potential as a tool in education as well as urban planning and development. As such, the atlas’ methodology has the capacity to diversify professional and institutional discourses on matters that concern ordinary citizens on a daily basis. The “generous, dedicated participation the team experienced throughout their past workshops cast light on how artistic practices can contribute to imagining other futures,” says De Vet.

The Atlas after its creation

The Subjective Atlas team has put careful consideration into the methodology of using artistic practices to “counter-map” a complex post-conflict context, and the participants were eager to publish their expressions. “I would recommend this training to anyone,” said Zerina Sirćo, an international relations and diplomacy student from Visoko.

For Adna Jeleč, a social work student from Sarajevo, the workshop provided “a new opportunity to express [her] opinion based on [her] experience and [her] knowledge” – a subjectivity the project’s team intentionally seeks out.

The Subjective Atlas team, in turn, appreciated the workshop in Sarajevo as “a crash course into history, culture, life, social fabric, administration, language, sayings, habits, food…” – setting them off on their venture to produce an atlas of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The workshop has clearly left an impression on local youth, who can use this activity to develop their artistic and journalistic skills. Their stories will undoubtedly contain insightful testimonies of their relationship to a country that grew throughout their lifetimes, without excluding lighthearted representations of Bosnian identity too. Thus, one can expect deeply personal, cartographic representations of the community from the Subjective Atlas of BiH, alongside images and stories of warm servings of burek and Bosnian coffee.