The wartime past of the region is still part of the present for many of its inhabitants, due to trauma, glorification of war criminals, and divisions on national grounds. As a result of the proliferation of false narratives, the unresolved issues of the past remain an obstacle to a more stable future.

A serious and objective history of the ‘brotherhood and unity’ that was destroyed by the war was buried along with those who unjustly lost their lives. In the countries of the region, official historical narratives are often completely contradictory. Vesna Teršelič, a peace activist, feminist, and leader of Documenta – Center for Dealing with the Past, Croatia, says that in democracies it is normal for the same historical events to be interpreted in different ways.

“It is normal to have different interpretations and narratives. I think it is legitimate to interpret the same facts in different ways, but there is a limit to that as well. Denial of facts about war crimes should be inappropriate, and denial of the worst crimes such as the Holocaust and genocide should be prohibited by law. In addition to the prohibitions, which are unfortunately a necessity in the region, the most important thing is responsible media, because the prohibitions themselves cannot ‘erase’ different narratives,” she explains.

Different interpretations and narratives of the wartime past should be approached with a dose of caution, as they often lead to a deepening of intolerance and the spread of hatred. For this reason, is extremely important to deal with the past in a healthy and objective way. For Nataša Maksimović, president of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Network for Building Peace, dealing with the past is extremely important for the future.

“To build peace means to be aware of yourself, but also of everyone around you. Accept them all with all that they are and do not judge. It is important to step into other people’s shoes, it is important to get into all those narratives, to feel them, to understand why they were created, what feelings are hidden behind it,” she says.

As complex as it is indispensable

Dealing with the past is a difficult but indispensable part of peace-building. Vesna Teršelič points out that the research work itself is a very complex process and that publishing research results is also a challenge due to the sensitivity of the topic.

“We talk about the layering of historical events every time we publish new research and publications, thus creating new interpretations, not only of the war events of the 1990s but also of other controversial periods of the 20th century,” adds Teršelič.

The opinions of young people are colored by the experiences and memories of the elderly, which, when war crimes are denied and their perpetrators celebrated, becomes problematic. Both young and old have become hostages of the past, which is so deeply intertwined with the present. Nataša Maksimović explains that we have been growing up for centuries with the idea that war every 50 years is a normal occurrence in this region.

“We pass on so many of these wartime traumas from one generation to another. In a way, we live in the past, not the present, and we don’t seem to have a future. Precisely for the sake of having a present and a future for new generations, it is important to deal with the past and start building peace,” elaborates Maksimović.

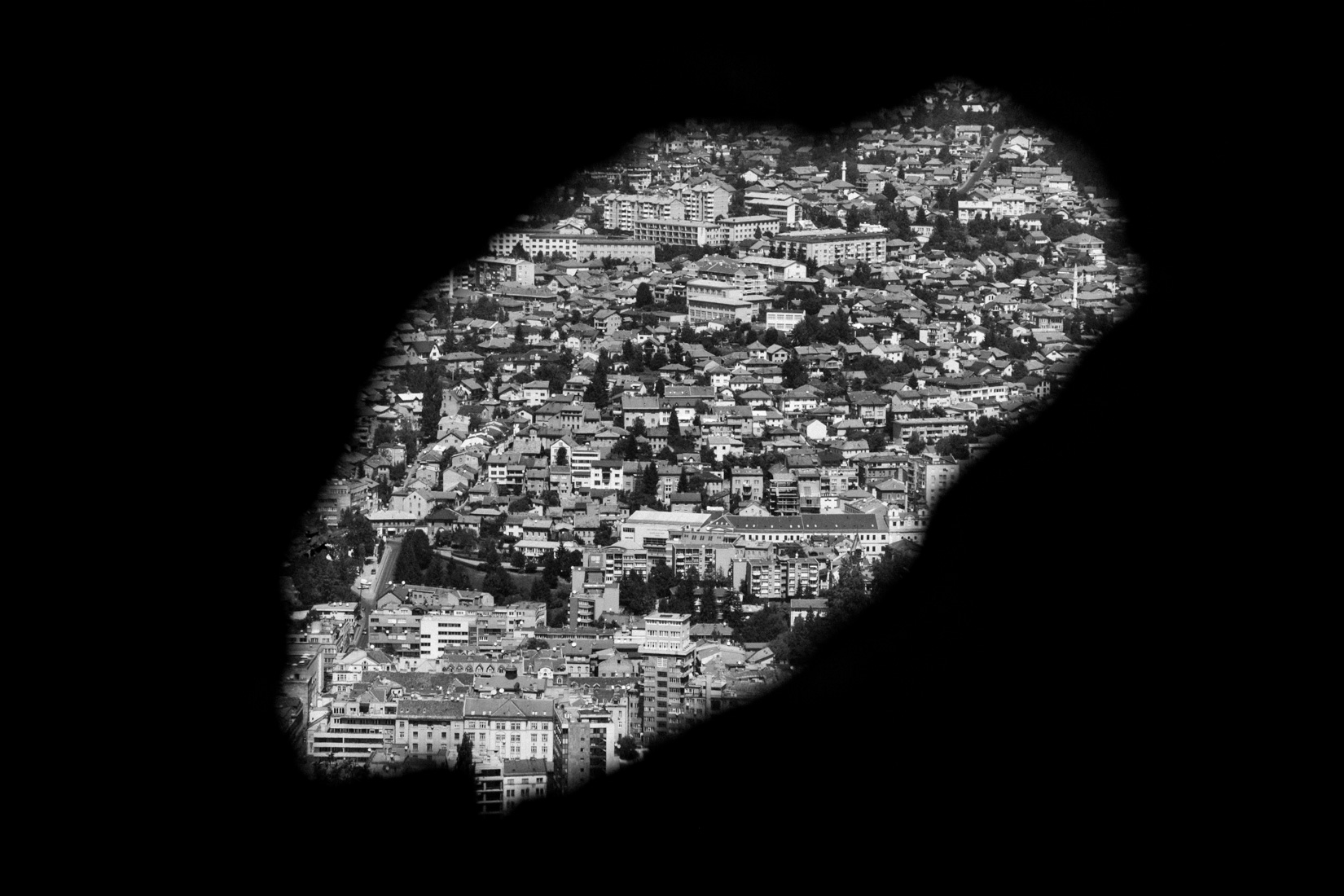

According to available data, between 130,000 and 140,000 people died in the wars in the former Yugoslavia. Of these, more than 100,000 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, more than 20,000 in Croatia, and more than 13,000 people in Kosovo. Approximately four million people became refugees due to the war, and 2.2 million people were displaced in Bosnia and Herzegovina alone.

In the post-conflict societies of the former Yugoslavia, more than two decades after the wars, conflicts have been waged with the sharp swords of inaccurate information. There is more talk about other people’s crimes and one’s own victims than vice versa, and emphasizing the facts of the war is often a thorn in the side of those who ignore the truth.

Truth is often seen as an attack on identity, on ‘nationality’. That identity – religion, nation, prejudice, propaganda – is a wall built to block out the facts.

For justice we need truth

An objective history of the events of the wars of the 1990s is crucial for the prosperous development of society. Its denial means that divided communities will not accept it. The basis of justice is truth, and to ignore the judicial truth means to rekindle the war mindset.

In this way, victims are diminished and what appears is a false sense of patriotism and an ideology of denialism. When patriotism, nationalism, and denialism are combined, not only what is essentially true is contradicted, but also a new dimension of truth is created contradicting all laws of logic. Nationalist-oriented politicians who reject the verdicts of the International Criminal Court contribute to all of this.

Those who resist false narratives, however, are paving the way for a brighter future. They build that path with facts, love, knowledge, and tolerance. They accept the facts and defend them no matter what.

“I don’t let discouragement swallow me up. I always try to look for the potential in people,” says Vesna Teršelič. Teršelič and those like her are driven by, as she puts it: “hope for change and inexhaustible optimism”.

__________________________________

This article was initially published in the first edition of MIR Magazine. MIR, which means ‘peace’ in Bosnian, is an annual publication and platform for young inventive people developed by the Post-Conflict Research Center and Balkan Diskurs. It is dedicated to individuals and organizations that left us a legacy of strongly built foundations to continue our fight for peace and justice.