In light of the recent events, Balkan Diskurs has been working on a series about the challenges faced by Bosnian children with special needs and their families. These are their stories.

Recently, photos were released showing the terrible conditions within the Pazaric Institute, a care home for children with special needs, after the ruling parties refused to address the problems. This action sparked protests across the country. To begin at Part I of this series, click here.

The future is my biggest fear.

— Muamera

Born in Sarajevo in February 2010, Harun showed no sign of developmental difficulties as a young child, but when his health began to rapidly deteriorate, he soon found himself in a seven-month-long battle for his life. Harun’s family took him to numerous State-run medical facilities and institutions in a desperate search for answers but received no guidance or support. In the end, they had to rely on private doctors, visiting specialists from Austria, and expensive steroid treatments to address his varied medical conditions. Harun’s mother, Muamera, and her family were left to cover all the expenses with no financial support from the State.

Harun’s health improved, but the fight was far from over and he was soon diagnosed with autism, hyperactivity, and underdeveloped speech. Many doctors attributed his condition to Muamera’s age (35 years old) at the time of his birth, she questioned, however, various aspects of his diagnosis. For example, she had often observed Harun sitting peacefully for hours without distraction or distress – a contradiction to the typical symptoms of hyperactive behavior disorders. Muamera looks back on her disputes with the doctors and the health care system as a turning point; Moving forward, she knew she would have to take a proactive role in obtaining proper care for her son.

Muamera and her son received some assistance from a local center for speech rehabilitation and a center for children suffering from sight deficiencies, however, they received no assistance, financial or otherwise, from the State. The absence of support for children and young people on the autism spectrum in BiH is sorely felt, as is the lack of resources provided to State-run facilities. Nobody is responsible for providing oversight to such institutions or to local centers like the one for speech rehabilitation to ensure they understand how to accommodate the needs of autistic and other special needs children. Muamera has had to turn to private NGOs and organizations like Education for All (EDUS) and Colibri to find the support and understanding that is missing from the public institutions.

When asked what the biggest obstacle has been thus far, she responds without hesitation: “The biggest problem is not that they don’t know about this issue, it’s that they don’t want to [know].” To Muamera´s great frustration, doctors and specialists often label Harun as “abnormal”, which reveals their willing ignorance. Their attitudes about the disorder, in turn, play into the stigmas that surround the disability. Muamera recalls one specific instance for which the familiar lack of understanding led to violence. “As soon as I mentioned Harun had autism, five nurses surrounded him and held him down like an animal. I started screaming. Imagine if somebody grabbed you from behind? How would you react?” This blatant absence of recognition and respect from those charged with helping the vulnerable too often leaves children and their families in despair.

The same disinterest is also present in the education system, against which Muamera has struggled in her efforts to secure the best possible education for Harun. The schools have made it clear that they are not ready to facilitate Harun’s needs and, despite her best efforts, Muamera has consistently run into an unwillingness to make any accommodations for her son whatsoever.

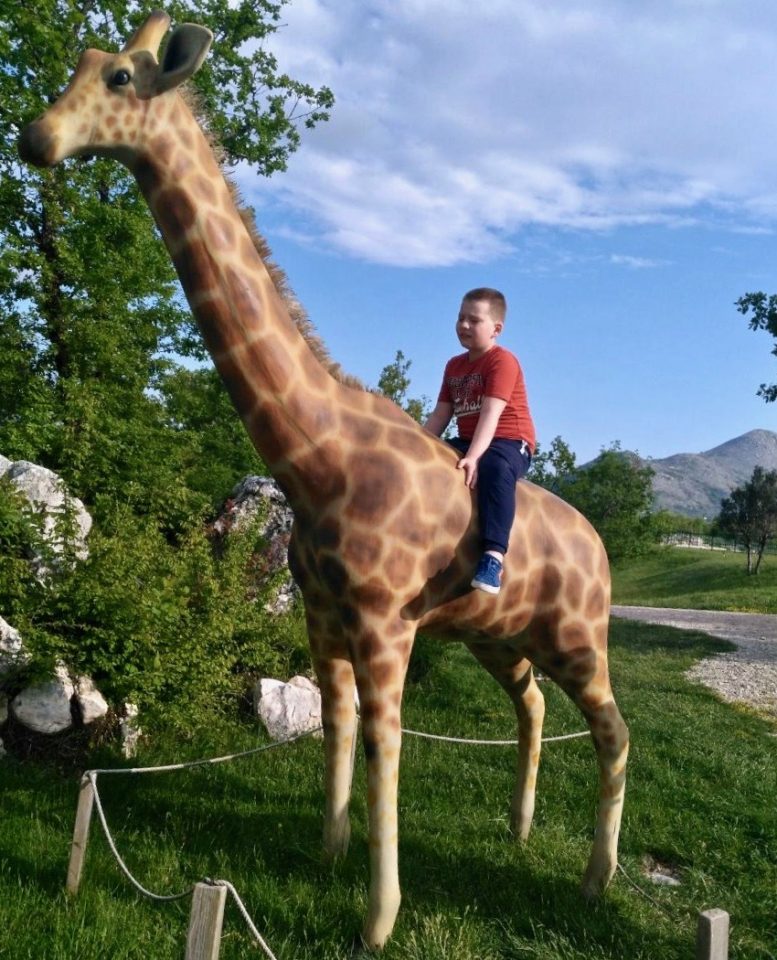

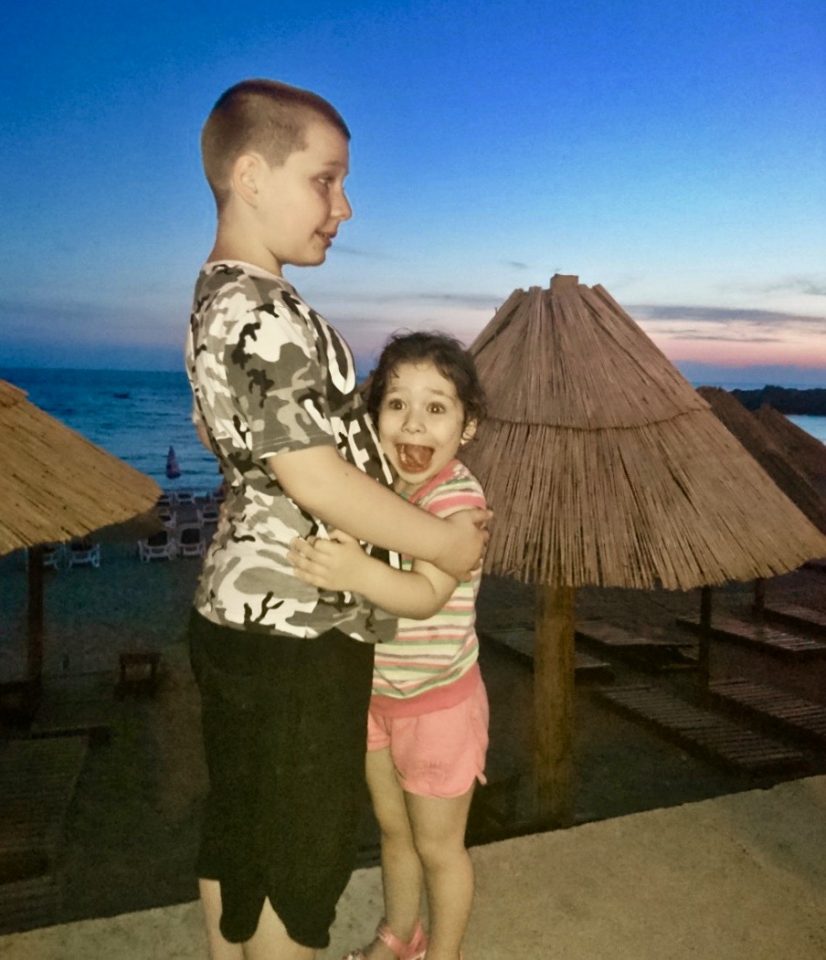

Without support from the official channels, Harun and Muamera have found help from an unexpected source. His four-year-old sister has taken it upon herself to help him by teaching him how to play and interact with others – activities that can be demanding for anyone with his specific challenges. Her young daughter has, thus, helped lift a heavy burden from Muamera’s shoulders.

The state of the Bosnian education and health care systems often leaves families with little hope for a brighter future for their children. In a country where nearly everyone is struggling to make ends meet, the government leaves the considerable expenses of doctors, therapists, and medications to the individuals affected. The constant worry that accompanies needing help but finding none forthcoming is only intensified by the static situation in BiH.

As with Mahmut’s mother Samija, the question of what will happen to Harun once Muamera can no longer care for him is ever-present. “If I’m not there for him, who will be? Harun might find safety and security, but it will not within BiH’s borders unless autism is better recognized and understood,” she concludes.

Part I – Educational Exclusion of BiH’s Most Vulnerable: An Introduction

Part II – Educational Exclusion of BiH’s Most Vulnerable: Mahmut’s Story